The youth have such an amazing way of giving adults perspective. Recently, I have been volunteering and mentoring a diverse group of middle school students. During my time with them I have been impacted by many things, but one thing in particular has nestled itself into my head and my heart. While working in the garden I began a conversation with a precocious 8th grade girl who told me that she would rather be doing something else because she didn’t see why working in a garden was important. I took this as a sign that as a group, we should come together and talk about why we were gardening and hopefully make some connections between the work we were investing in the garden and the kids’ other areas of interest. I was truly hoping to uncover some nice connections—fingers crossed.

For the most part we talked about the importance of knowing where food comes from, healthy eating habits, seeing projects through from beginning to end, and learning about the environment and how we are all a part of nature. They all were really engaged. The conversation then moved into the students sharing what they wanted to be when they grew up. I was sitting among future teachers, lawyers, doctors, and scientists. They asked me what my job was, and I told them that I work with nonprofits to raise money and awareness for important causes like the environment—the room was silent. Then my sweet little precocious 8th grade friend said, “Why do you do that? Don’t you want to make money, be successful and be the boss?” I asked her why she assumed I couldn’t get all of those things while working in the nonprofit sector and she said, “Because you are black and all the other leaders who have helped us with our garden and at our school have been white.” I was speechless. At 13 years old, just embarking on young adulthood, she already had this skewed perspective. For the rest of the afternoon, I was distracted, trying to wrap my head around this young girl’s comment—was her perspective really all that skewed?

Nature is overflowing with vibrant colors so why isn’t the movement to protect it? What began as a whisper is now turning into a roar—where is the diversity in the leadership in the environmental movement? Even those outside the nonprofit sector are starting to notice the glaring lack of racial and ethnic diversity. In fact, one Guardian headline asks, “Why are so many white men trying to save the planet without the rest of us?”

In 1967 Sydney Howe, a pioneer for the environmentalist movement, commented that environmental advocacy is an institution that has not been racially accepting. Nearly 50 years later, Howe’s comment still rings true.

Many mainstream green groups have been accused of having a race problem or “green ceiling” despite two notable factors:

- There is an overall growing awareness of how pollution and climate change are directly (and negatively) impacting low-income people of color; and

- Minorities account for 36% of the population nationwide, a figure that is expected to increase dramatically over the next few decades. In fact researchers at the Brookings Institute have determined that the minority population for individuals 18 and under will reach the majority in less than three years. Furthermore, by 2027 the 18-29 age group will become the majority as well.

It is time to move away from the old-school model of the homogenous environmental organization.

Recently, Will Parish (Founder and President of Ten Strands) and I attended a community forum at the Commonwealth Club called Green 2.0: Breaking the Green Ceiling that brought together an impressive gathering of environmental advocates. Environmental forums are nothing new to the Bay Area, but what was different about  Green 2.0: Breaking the Green Ceiling was the focus: the lack of diverse leadership in the movement. To address this, Green 2.0 has partnered with Guide Star and the D5 Coalition to increase transparency on racial and ethnic diversity in the mainstream environmental movement as part of an overall comprehensive strategy. This follows the recent release of The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations: Mainstream NGO’s, Foundations & Government Agencies, commissioned by Green 2.0 and authored by Professor Dorceta Taylor. The report highlights the disparities in race, class, gender, and culture within organizations with an environmental focus. It examines 293 environmental organizations nationwide, and is comprised of data from 191 conservation and preservation organizations, 74 government environmental agencies, and 28 environmental organizations.

Green 2.0: Breaking the Green Ceiling was the focus: the lack of diverse leadership in the movement. To address this, Green 2.0 has partnered with Guide Star and the D5 Coalition to increase transparency on racial and ethnic diversity in the mainstream environmental movement as part of an overall comprehensive strategy. This follows the recent release of The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations: Mainstream NGO’s, Foundations & Government Agencies, commissioned by Green 2.0 and authored by Professor Dorceta Taylor. The report highlights the disparities in race, class, gender, and culture within organizations with an environmental focus. It examines 293 environmental organizations nationwide, and is comprised of data from 191 conservation and preservation organizations, 74 government environmental agencies, and 28 environmental organizations.

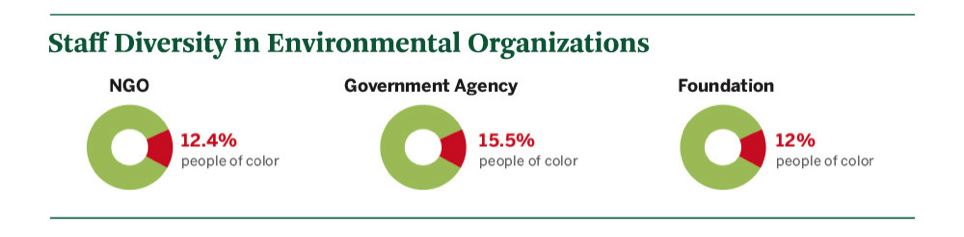

The report found that the “green ceiling” in fact does exist, and that less than 16% of people of color have been afforded the opportunity to break into it, despite the fact that people of color make up a third of the US population.

As Will and I sat among the “who’s who” of the movement at the Commonwealth Club, I knew and felt something special was happening. Representing mainstream environmental organizations were Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune, and Earthjustice President Trip Van Noppen. Also lending their voices issuing a call to action for more transparent diversity data were: Tom Steyer (Investor, Philanthropist and Advanced Energy Advocate); Hank Williams (CEO of Platform and a tech entrepreneur who has been featured on CNN’s Black in America); Tomás Torres (San Diego Border Office Director from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency); Laura Butler (President of Talent Management and Chief Diversity Officer from PG&E); Malik Yusef (Five-Time Grammy Award-Winning Artist, Activist and Executive Producer of the Climate Album H.O.M.E. Heal Our Mother Earth); and Peggy Saika (President of Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders in Philanthropy).

The universal tone was that it’s time for change and we must all do our part in uncovering and addressing the systemic diversity crisis the movement is drowning in.

So why are minorities not infiltrating the workforce as quickly as women or as rapidly as they are increasing in overall population within the nation? As I ponder this question I can’t help but think of my dear 8th graders. If they don’t see a place in leadership for people who look like them in the environmental movement, then who will rise to the occasion and fight this fight through their lens? After all, movements are won when they are lead and run by diverse perspectives, ideologies, and approaches.

The number of minorities in leadership roles among conservation and preservation organizations is alarmingly low—in fact, the figure is less than 10%. Furthermore, minorities only make up 10% of all grantmaking foundation leaders, and less than 20% of presidential roles within government agencies.

Coincidentally, white women have infiltrated leadership positions at a significantly faster rate than other minorities. The study discovered that women held half of the near 2,000 leadership positions within the conservation and preservation organizations observed, and white women held 60% of intern and new hire positions within these organizations.

According to Taylor’s report, minorities aren’t showing up because there simply aren’t job opportunities for them to show up for. Most hiring comes through networking channels that they simply don’t belong to, such as foundation networks or word of mouth. More often than not, this leaves little room for recruitment efforts that target minority environmental professional organizations and educational institutions. The study also observed that many organizations were devoid of a diversity manager. Studies show that having a diversity manager on staff makes it more probable that an organization will have more minority paid staff and interns.

This crisis raises important questions about the role of philanthropy in the environmental movement as well. How is the movement being funded? Do grantmakers encourage outreach to communities of color? Is funding being evenly distributed to both large national nonprofits and smaller grassroots organizations?

Two years ago, the National Center for Charitable Statistics (NCRP) published Cultivating the Grassroots: A Winning Approach for Environment and Climate Funders as a part of a report series by Sarah Hansen, former Executive Director of the Environmental Grant Makers Association. The report’s purpose was to help advance the dialogue around increased engagement with communities of color involved in environmental efforts and for increasing funding for such efforts.

The report went on to outline how environment and climate funders tend to favor top-down approaches to grantmaking and public policy by funding larger, well-resourced organizations. NCRP concludes that environmental funders need to invest more in high-impact grassroots organizing so that communities can mobilize and demand environmental change from the bottom-up. Some suggested steps that foundations can take to support environmental action include:

- Directly funding grassroots initiatives led by and for marginalized communities

- Pushing for greater diversity among their staff and that of their larger environmental grantees

- Motivating large mainstream organizations to partner with grassroots organizations

For example, Inside Philanthropy just reported on the Libra Foundation’s application of a justice lens to their environmental philanthropy—part of a growing trend in which “more climate funders are getting attuned to the role of low-income groups in climate work.”

Another high-power partner recognizing the importance of diversity in the movement is the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) headed by Rhea Suh, former program officer at the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Suh is the first woman of color to lead a major mainstream environmental organization. In an interview with Grist, Suh comments on the role of philanthropy and states, “I think it is both the responsibility of foundations—which have, in some ways, the luxury of thinking about trends, perspectives and opportunities—to think about where they’re going to get long-term gains and significant opportunities [from community-based organizations].”

A more equitable distribution of philanthropic dollars among environmental justice nonprofits could help ensure equity at all levels of the fight for a more sustainable future—a healthy future that we all desire. One that I hope will inspire youth, like my middle school mentees, to know that they can be a part of the environmental movement—and furthermore they can be a success at it. There is no room for neo-liberalism in the movement where the leadership doesn’t reflect the complete picture of the benefactors. The picture of nature is too colorful not to include us all.

Going forward, environmental advocacy cannot succeed if

its leadership does not reflect the communities it seeks to mobilize and benefit.

~Sarah Hansen, Author of Cultivating the Grassroots:

A Winning Approach for Environment and Climate Funders

So is there a silver lining? The answer is yes. The conversation is happening and organizations like Ten Strands are championing inclusive efforts to ensure that our youth are getting quality access to environment-based education—regardless of gender, class, or race. This is something I can proudly support. As I prepare for my next meeting with my middle schoolers, I am looking forward to my role in mobilizing the next generation of diverse eco rock stars.

The time is now—no more excuses.

4 Responses

Interesting article, Cory. I must admit it’s something I’ve never thought about. Seems like there’s a need for education, both in the non-profit industry and in the general population. Thanks for bringing it to our attention. I’ll repost it in hopes others will join in your concern.

Truly inspiring Cory! I’ve been thinking about this for the past few hours–you have given me something to think about. Thanks

Interesting article, Cory. I must admit it’s something I’ve never thought about. Seems like there’s a need for education, both in the non-profit industry and in the general population. Thanks for bringing it to our attention. I’ll repost it in hopes others will join in your concern.

Truly inspiring Cory! I’ve been thinking about this for the past few hours. Thanks for pushing me and my awareness.