Since May 2020, the National COVID-19 Outdoor Learning Initiative (NCOLI) has created dozens of free resources to support districts to center equity by returning students to school safely through the use of outdoor spaces for learning. In the spring and summer of 2021, Ten Strands, The Lawrence Hall of Science at the University of California, Berkeley, and the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE) partnered to create additional resources, listed at the bottom of this page, specifically focused on teaching and learning in the outdoors. CCEE is a statewide agency designed to help deliver on California’s promise of a quality, equitable education for every student, working alongside the California Department of Education and other partners. In July 2021, Karen Cowe, Ten Strands’ CEO, and Linda Livers, a Ten Strands consultant, interviewed three staff members from The Lawrence Hall of Science who worked on the project: Sarah Pedemonte, professional learning specialist; Vanessa Lujan, deputy director of learning and teaching; and Craig Strang, associate director.

Q: Why did you apply for support from CCEE to advance the National COVID-19 Outdoor Learning Initiative (NCOLI) in California?

Vanessa: There seemed to be an opportunity to really elevate the prominence of outdoor learning and how it is a critical piece among district strategies; not only during COVID-19, but also as a longer-term strategy for supporting students. Support for outdoor learning was also a unique contribution to the CCEE portfolio of support for districts and schools. The CCEE request for proposals was more oriented toward distance learning and professional learning to support distance learning, and we presented an entirely different approach to get kids back in-person outdoors as quickly and safely as possible—the opposite of reinforcing distance learning. This was seen as unique by CCEE and they were willing to support this work in addition to other distance learning efforts, giving further value to the effort, especially in California. We’re grateful that Roni Jones, the assistant director of the system of support, and Michelle Magyar, the assistant director of business operations and strategic engagement, saw value in the approach we took.

Craig: We initially got involved in NCOLI, as a founding partner, to specifically address the huge inequities we were seeing. At the earliest stages of the pandemic, when the first shelter-in-place orders were issued and schools were shutting down, and there was this shift to remote and online learning, we immediately knew that this was going to have a huge negative impact on all learners, and a hugely disproportionate impact on learners that did not have access to high-speed Internet, access to devices, a caring adult available to help them navigate the online system, or a quiet or private place to participate from home. We knew that whatever we were imagining was going to be worse for low-income communities and communities of color. And, it ended up being actually worse than we even imagined. Savage Inequalities came to mind, to quote the title of a book from 20 years ago. So, this idea of leaving kids at home in unsafe and inhospitable contexts from which to learn became absolutely unacceptable. We have been setting about since those earliest days to try and create a different approach, a different paradigm about a response to the pandemic; not to make online learning slightly more accessible to 20 more kids or 5 percent more kids, but rather to eliminate remote learning as quickly as possible and get kids back in person with a caring adult in a safe and healthy, engaging, and inspiring context outdoors.

We knew outdoor learning could provide a significant part of a remedy to try and heal some of those traumas, injustices, and inequities. We started the work with Ten Strands, Green Schoolyards America, and San Mateo County Office of Education – and were quickly joined by many others — on a national level through the NCOLI. CCEE then gave us this incredible opportunity to really develop resources that were tailored for California public schools, which was an important contribution to the larger national effort.

Q: What capacities are important for schools and districts to think about and consider when supporting outdoor learning?

Sarah: Several capacities emerged as we worked directly with districts and through many conversations with schools and districts while they were thinking about moving from 100 percent remote back to the classroom with small cohorts, hybrid models, and on to full in-person instruction. It became apparent that there was an ecosystem of support that was needed around outdoor learning. We developed six key considerations for an outdoor learning ecosystem that guided our resources, and we believe, could help support districts in considering each instruction scenario. In no particular order, they are:

- Equity first: Design at the margins, design for the most vulnerable students that are furthest from opportunities, and this will ensure that the plans would work for all students.

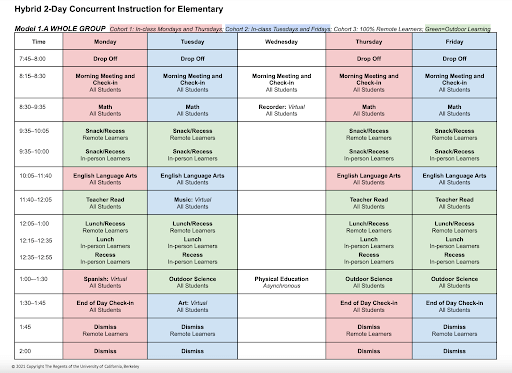

- Prioritize science: Allocate equal amounts of time to science as to other core subjects. To this end, we designed some schedules to demonstrate what this might look like as a resource. The outdoors is a very natural context for learning science.

- Utilize outdoor spaces: In addition to the schoolyard, it’s important to consider all local places that could be used for learning and the different ways that they could be used.

- Staffing: Consider staff who might be able to work with different cohorts of students. There might be outdoor education teachers from community partner organizations, who are already familiar with the students and also have expertise in teaching outdoors.

- Communicate: It became very apparent through our conversations that the idea of doing something new meant regular, consistent channels of communication and feedback were important. Professional learning: Investment in outdoor professional learning for school leaders, teachers, and staff would support students in their outdoor learning.

Vanessa: These outdoor learning key considerations were inspired by a set of seven key dimensions that we developed and use in our capacity-building approach for equitable, high-quality science education, and environmental literacy in districts. The outdoor learning considerations are uniquely articulated, precisely because of the fluidity and ever-changing conditions caused by the pandemic. The new outdoor learning considerations align with what we know about district capacity building and attend to the quick cadence of decisions being made within district and school systems. Undergirding the considerations is the understanding that outdoor learning is the solution and an assumed vision that outdoor learning supports the accomplishment of larger school district goals and priorities for supporting equity, health and safety, wellness, and academic learning, among others.

Craig: The original seven considerations for district capacity building are still important, but are really intended for the long haul and building of a strong, stable, coherent system of support for science and environmental literacy within a school district. We want that process, for instance, to be inclusive and to be iterative. And, we knew that the phases of responding to the pandemic were going to be timely and have a greater sense of urgency that was not appropriate for the longer term capacity-building episodes. The outdoor learning key considerations instead address what we found districts needed in the moment, like enhanced communication, which is always important in a school district and there’s never enough of it. But, when safety considerations from the health department are changing weekly or daily, student schedules are changing weekly or monthly to small cohort, hybrid, or remote learning, and teachers aren’t sure if they’re going to be having a staff meeting after school or preparing for their online lessons, continual accelerated communication became an important consideration.

We just knew that the inequities due to distance learning were going to be huge no matter what, so we realized that the solution was not to improve distance learning, but instead work around it to design at the margins by eliminating that system and bringing kids back to school as quickly as possible. This meant immediately considering what outdoor spaces could be used tomorrow, immediately figuring out what kinds of ways to communicate with parents in the school district, and immediately figuring out what community partners could enhance your workforce and your capacity to safely work with small cohorts of kids in person. So, all of those considerations were arrived at to address urgency, because not only was the situation changing daily, weekly, and bi-weekly, but there were kids just slipping through the cracks, disappearing, unaccounted for, that hadn’t been heard from, that we were losing, every single day of the pandemic. We were trying to create systems for re-engaging with those kids and their families.

Vanessa: One outdoor learning key consideration is the prioritization of science. During the pandemic, less science was happening during digital learning, despite evidence that students were more engaged during science time. The facets of outdoor learning are really unique and valuable, and it is a natural setting to emphasize science and engage kids in the outdoors and natural spaces. Outdoor learning is not only the right choice for health and safety, but also in the context of nature and science with which to learn math and English language arts (ELA).

Q: What primary role do you play with statewide support for environmental literacy in California?

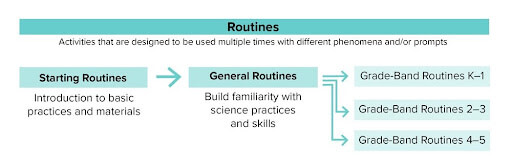

Craig: The Lawrence Hall of Science has been involved in environmental education, environmental literacy, and outdoor learning for decades, going back to the late 1960s–early 1970. There was the development of Outdoor Biological Instructional Strategies, one of the very first published, research-based outdoor curriculum programs, and also the development of A California Blueprint for Environmental Literacy – which many organizations throughout the state were involved in with the Lawrence, including Ten Strands, the California Academy of Sciences, and the California Department of Education serving in co-leading roles. Since 2014–2015, we’ve been really focused on the relationship between environmental literacy, science literacy, and the areas where environmental literacy crosses over into history-social sciences, the arts, and health education. A lot of the thinking and framework building had been done, so we were poised to respond during the crisis of the pandemic with some solutions that we weren’t inventing out of whole cloth in the moment. We had resources, approaches, curriculum materials, partners, and the BEETLES project, created in 2012, that develops professional learning resources and student learning resources. So, we had quite a bit available that was ready to be adapted for this very particular need that arose during the pandemic.

As the NCOLI library of resources evolved, there was a natural emphasis placed on developing spaces for kids to learn outdoors that had to do with infrastructure, buildings, facilities, and grounds. And of course, there was a huge priority placed on the health benefits related to the low transmission rates of COVID-19 outdoors. We wanted to ensure that the benefits of learning outdoors were equally represented, too. The Lawrence has a long tradition of exploring teaching and learning and translating research about learning into tools, curriculum, resources, professional learning materials, and capacity-building resources. This project really gave us the opportunity to shine a light on the benefits of learning outdoors and learning about the environment, which was so necessary during the pandemic.

Vanessa: A lot of our CCEE project efforts centered around our deep knowledge of capacity-building in school districts and expertise in ongoing district partner relationships through our various collaborations at the Lawrence, like BaySci, an initiative to help support districtwide capacity building for the implementation of equitable, high-quality STEM education across the state of California. This expertise informed the development of tools, resources, offerings, and support for districts in a way that is unique to partnerships, doing things with districts, district administrators, and teacher leaders, rather than to them.

Q: From your experience supporting teachers to embrace outdoor learning during COVID-19, and thinking to the future, what are some of the challenges and opportunities?

Sarah: Throughout this time, we facilitated a professional learning community (PLC) to focus on prioritizing outdoor learning and environmental literacy in the context of the 2020-2021 academic year and beyond. This community of district point people discussed their approaches to environmental literacy, challenges they were facing, and strategies for safe student learning and future opportunities. Across the group, it was reported that districts were open to and supportive of environmental literacy efforts, but there remained many challenges for outdoor learning and resource uptake. We encouraged the districts in the PLC to mobilize immediate responses to the pandemic, with small cohorts to prepare for hybrid learning and to be poised to learn outdoors. In some specific cases, districts were able to do that.

Craig: In many cases, the noise, chaos, and changing context were overwhelming, and district leaders felt somewhat marginalized within their own district administration, so they started thinking more about post-pandemic learning than pandemic learning. Many districts were unable to hold districtwide meetings or create comprehensive plans supporting outdoor learning, but there was an overall shift toward approaching school reopening in the fall, better prepared than before the pandemic.

Sarah: The PLC discussed common inequities of environmental literacy efforts that are teacher-based or site-based, or seen as an add-on and not part of core curriculum conversations. As we considered future environmental literacy efforts, the PLC determined the need for districtwide efforts, professional learning, and the inclusion of environmental literacy in core curriculum and instruction conversations. We considered possible steps the district point people might take at their districts to address these challenges. For example, when teachers are asked by their high school students to include community-based projects in their instruction, they need support at the table with the high school department heads; projects that are seen as post-pandemic electives need to be integrated into the classroom curriculum, and teachers need to be given support to lead now. It was also acknowledged that because of pandemic related complexities, some challenges, such as getting some outdoor learning resources into the hands of teachers were too great, but that the PLC conversations were helpful to figure out why the resource was not usable at that moment, what needed to happen, and what conversations had to happen to make the integrations more permanent.

Q: What were some important considerations for the creation of resources and why did you choose that particular approach?

Sarah: Educators didn’t have a lot of materials in this new landscape or a lot of time to create them, so sample schedules and instructional material resources were the first things that we wanted to provide. We needed instructional materials to be presented in a way that educators could figure out which would be the right materials for them, using criteria such as time, setting, comfort with the outdoors or with science, and who would be leading the students. We wanted the resources to be a carefully curated collection, small chunk content areas that were not overwhelming, that would be easily accessed on the NCOLI website. In this way, we were able to provide immediate support for educators with groups of students outdoors.

We knew that some teachers were continuing to use their district’s adopted science curriculum. Working with the curriculum developers, we created resources that identify opportunities for taking that learning outdoors. Our approach was urgent and in the moment, but we’re hoping that there’s a life beyond COVID-19 for outdoor learning and these resources.

Vanessa: It is important for us to provide multiple instruction model resources — hybrid, small cohorts, and full in-person. We saw districts and schools bring small groups of students on campus who were most acutely feeling the effects of distance learning issues and challenges. We saw districts transitioning quickly into the hybrid model. And then, importantly, fully in-person. Currently, with the ebb and flow of the COVID-19 variant spread, we are seeing instruction transition more fluidly between these models. The various tools we created for the different instructional models are an important piece.

Q: What is important for schools and districts to know about when launching outdoor learning and supporting outdoor learning long term?

Craig: The basics that we want districts to know about is that the outdoors is a viable, important, effective, healthy place for kids all the time. Not just during a pandemic, not just during 68-degree weather, not just when you’re doing one outdoor activity in the garden, but that the outdoors is a resource for learning all the time, and it should be the first option. As a starting point, educators should ask, “can we do this outdoors?” If it’s impossible, think about going inside and what it would look like to do it inside rather than the other way around. That aspect of reconnecting kids and teachers with the natural world outdoors could and should be a central purpose of schooling, not an accident that happens once in a while when it’s impossible to be indoors.

Sarah: Our State Board of Education and the Department of Education support outdoor learning. Not only is outdoor learning articulated as an important instructional approach (along with project-based learning and the 5E Model) in the California Science Framework, it is included in other disciplinary frameworks too; history-social science, health, and the arts, and math coming up in early 2022.

Vanessa: Throughout all of our work, we receive constant reminders that we are actors within a system. I think that elements of the system that have always been important, like a strong vision and strong leadership, whether that’s from the district superintendent or a school principal, are still really important. And, that’s tied directly to how districts use their funds to engage with outdoor learning partners. As we look to the future, it’s important to think about those system aspects that have always been important and will continue to remain important for supporting outdoor learning.

Q: What opportunities do you see in the near future for supporting outdoor learning and learning recovery?

Craig: There’s a huge and unprecedented amount of funding that’s available to California schools right now explicitly focused on remedying and healing the inequities and the injustices that occurred during the pandemic. They’re using language like “learning loss” or “unfinished learning” and addressing social-and-emotional learning and trauma-informed instruction. We know that the kids who suffered the most from that learning loss and trauma are low-income and students of color, and that’s what the expanded learning opportunity funds are for. I think we can position outdoor learning as an important strategy for addressing those concerns — spending quality time outdoors with well-trained, caring adults is the best remedy possible for those kids. We need to make that case and carry that message forward. It’s not an obvious solution, it’s not the first place that schools are going to look, but I think that the opportunity is huge for us to make that case and to demonstrate the incredible power of spending time outdoors.

The survey of literature that was done by Stanford last winter documents a decade’s worth of research to demonstrate the benefits of being outdoors for learning, social development, emotional development, and health purposes. There are ten reasons why being outdoors is better than being indoors for almost any given activity. And, this is not an agenda of the environmental community, it’s not a fringe community that’s pushing some strategy. UCSF Children’s Hospital is conducting research on the benefits of being outdoors. Learning researchers at Stanford and many other tier one research universities are all trying to understand how kids learn more, stay engaged more, are calmer, are more ready to learn, and are more able to learn after spending time outdoors. This is a phenomenon that exists and is hardly controversial anymore.

Sarah: Two resources come to mind, the 100 percent in-person instructional plans and the approach to walking field trips. We carefully created each of these resources through an equity lens, asking, “how does this support equity?” Access to field trips and outdoor learning has often been inequitable and the walking field trips model is one approach from a district’s outdoor learning instructional plan that is designed to include all students. The PLC is an extremely valuable opportunity to bring district leaders together.

Q: Anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

Craig: Throughout the pandemic, this crisis of shutting down our schools compels us to rethink education, rethink schooling, and rethink our priorities. What we’ve seen is that it doesn’t happen naturally. Rethinking is not a foregone conclusion, and we shouldn’t assume that rethinking is taking place. The most powerful force is to revert back to previous educational practices and to work toward getting back as much as we can have of what we thought was normal. It really is going to take community-based partners and the larger community of stakeholders in the state of California to bring about any significant change. For very good reasons our education system is built to be stable and not to change quickly. And that’s what we’re seeing — very little change is likely unless Ten Strands, Green Schoolyards America, The Lawrence Hall of Science, Justice Outside, and all community partners speak loudly and forcefully with one voice to say that what we had before was not good enough.

Resources developed as part of this project:

- Instructional Materials

- Short, Stand-Alone Outdoor Science Activities Menu

- Extended Outdoor Science Activity Sequences

- Enhancing Adopted Science Curricula for the Outdoors

- Daily Schedules

- Scheduling Considerations for Outdoor Instruction

- Changing the Schedule at Your School

- Schedule Samples

- Instructional Plans