Eight.

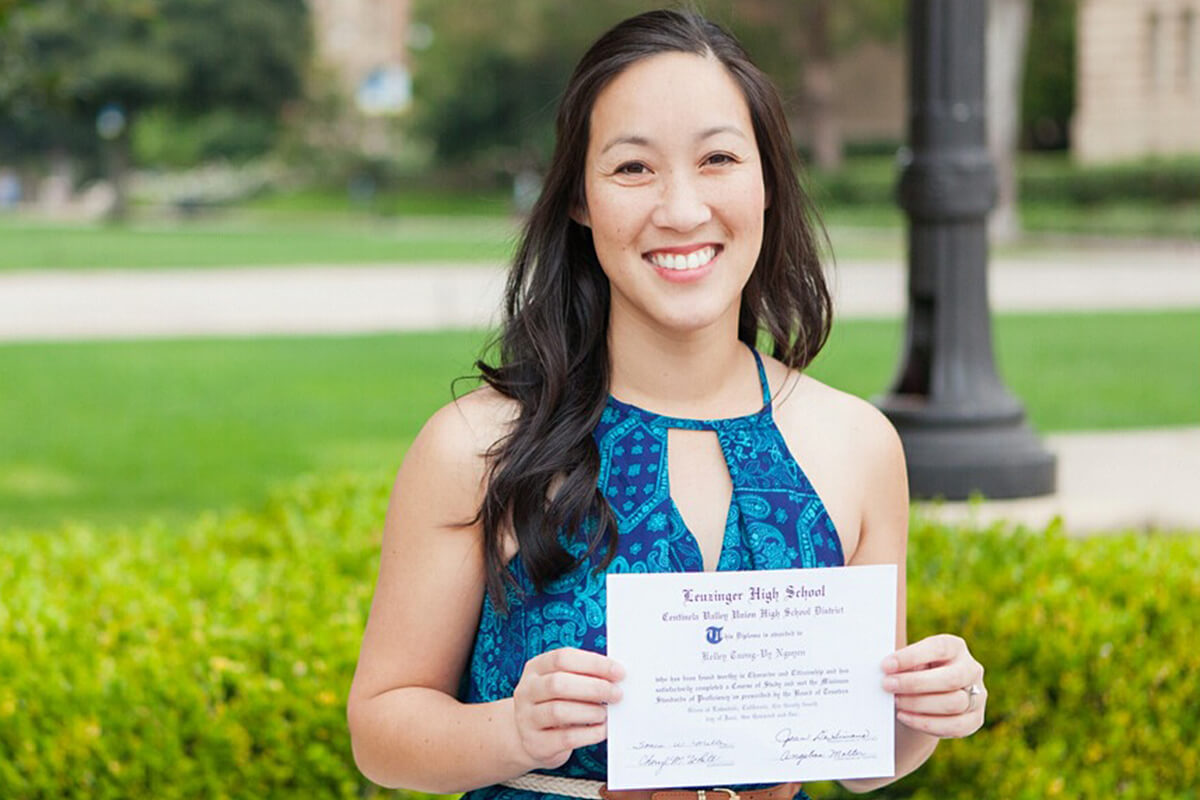

This was the percentage of students from the Title 1 high school I attended in Los Angeles who enrolled in and completed a degree at a four-year university. My senior class had nearly 1,000 students at the beginning of the year. At the end of the year, roughly 500 proudly earned a high school diploma. Roughly 50 of us got into a university, and 8 percent graduated. Please let that sink in.

My journey into becoming an advocate for climate science education, with a focus on social justice and environmental inequities, is deeply rooted in my own schooling experiences as a Southeast Asian American growing up in the inner cities of Los Angeles. At my old school, we used to joke that the security bars surrounding campus weren’t to keep students in but to ensure that teachers didn’t try to escape. That was all too funny, until I went back to my community as a high school chemistry and nanoscience teacher. Early on in my teaching career, I thought that building authentic relationships with students and teaching science through a social justice lens would be enough to help them break the cycle of poverty. Optimistically, I wanted them to look back one day and say, “100!” Not eight.

Throughout my years of teaching, I discovered that, beyond their core values, what fueled and activated the agency already within my amazing students was climate change education. It all started when we watched The 11th Hour (Conners Petersen & Conners, 2007). This documentary highlighted the larger problems that connected to the local issues I was already exploring with students: environmental justice issues ranging from a lack of access to clean air, water, and energy; healthy food; land; and much more. Before the film, I was teaching about these issues in my chemistry class without a larger context to connect them to. But after watching the film—along with Chasing Coral (Orlowski, 2017), Racing Extinction (Psihoyos, 2015), Before the Flood (Stevens, 2016), and many others—my eyes were opened to how I could design storylines to address this urgent and intersectional problem, which is exacerbating social justice issues in our communities, in some more than others.

Using storytelling with visuals that personalize and provide context to students brought meaning to my classes. Students shared about their lived experiences and where they saw the direct and indirect impacts of climate change on their communities. They were definitely furious that they hadn’t known about the climate crisis sooner. But, just as great scientists do, we continued to explore the issues, driven by their thirst to expand on current knowledge that is connected to creating solutions. My class felt a purpose in grounding the science content, and they had a shared vision for what the future could be if we took immediate action. My students felt it too.

When we think about 21st-century science education, we have to wonder whether students are learning about the science needed to address the problems of today. Rethinking science education means that we need to ask deeper questions about whether or not schooling works or was designed for everyone. Bryan Brown addresses this issue in his Science in the City: Culturally Relevant STEM Education (Harvard Education Press, 2019), by explaining the generational education dilemma that reinforces current inequitable educational norms. For today’s generation of underrepresented students, we can see that their grandparents had little to no access to education in 1940s America. And their parents grew up in the mid-1960s, when people of color were fighting for educational and civil rights. The current generation of students are the first to have full access to education—we call them First Gen. Until only recently, education was written for one audience in mind. So rethinking science education means that we have to deconstruct science to ensure it is purposeful, meaningful, and equitable. For the thousands of students I’ve connected with, climate science and education for climate action has allowed me to engage and position them authentically as capable change agents.

In my upcoming book, Teaching Climate Change for Grades 6–12: Empowering Science Teachers to Take on the Climate Crisis Through NGSS (Routledge, 2021), I support educators in thinking through what using climate change as anchoring content should look, feel, and sound like. What I have learned is that the climate crisis threatens our ability to survive on this planet, but also that humans are a highly resilient and intelligent species. This became my dissertation topic for my work through the UCLA Educational Leadership Program. I connected with nearly 50 local environmental organizations through the California Regional Environmental Education Community (CREEC) Network to learn about the impacts of climate change, and then I connected more widely with national educational directors to learn about the big ideas of climate science.

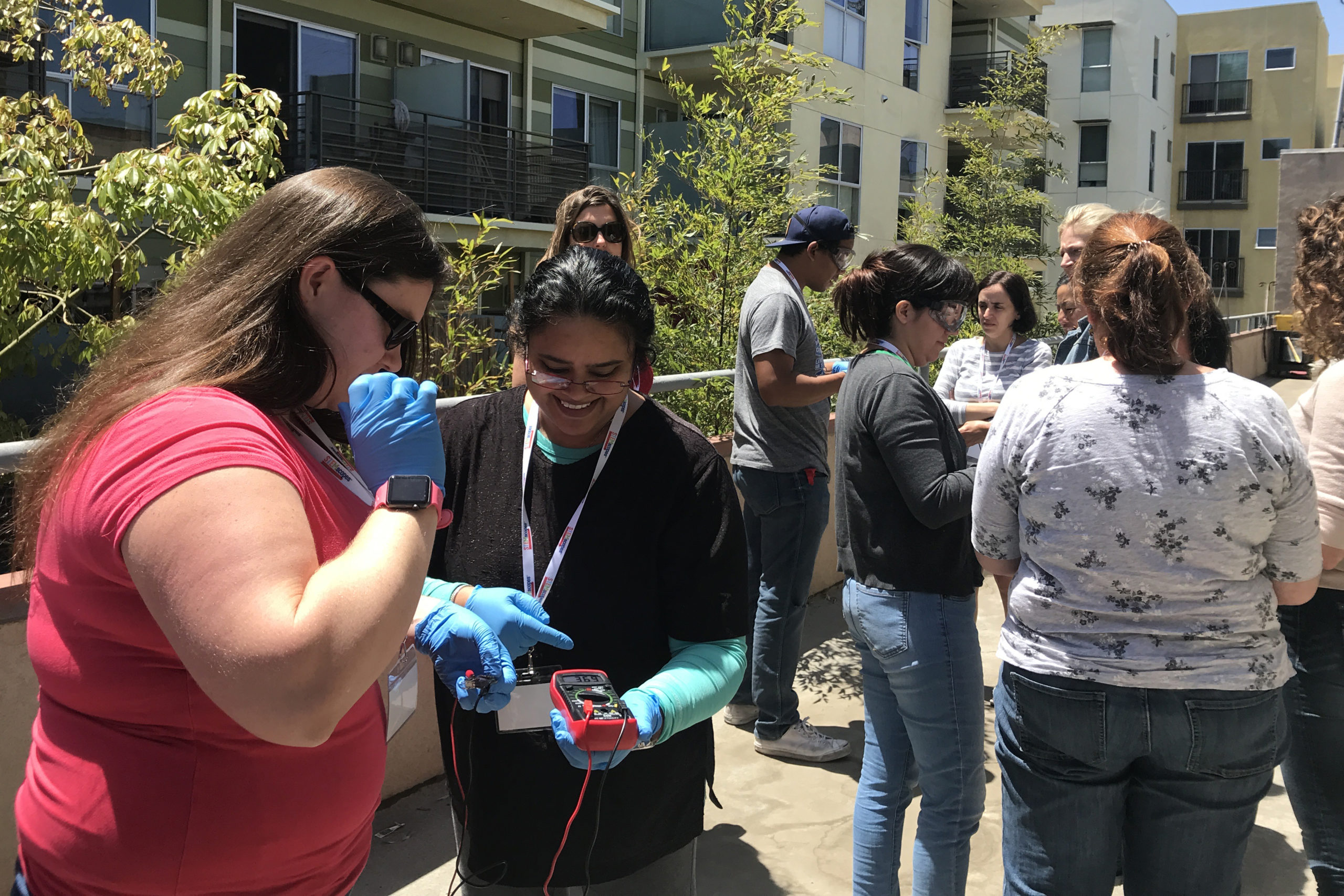

I translated my findings, incorporating research-based approaches, to create meaningful multiday programs for teachers at four nonprofits: (Aquarium of the Pacific, Heal the Bay, Reef Check California, and Cabrillo Marine Aquarium). In going through this process, I have learned a great deal about what works with teachers and about what doesn’t support teachers when they try to enact in the classroom what they learned during professional development. It always comes back to teachers’ underlying values and beliefs about science teaching and how students should learn, influenced by culture, identity, implicit biases, personal experiences, views of schooling, and so on.

It’s never too early to teach about environmental stewardship, the changing earth, and how climate change currently impacts living species and ecosystems. Although it was definitely hard to see my three-year-old cry when the last truffula tree was cut down in The Lorax (Seuss, 1971), as a five-year-old now, he is already a climate warrior who appreciates nature and the free, magical gifts it gives us, such as oxygen, energy, food, and medicine. And these days, my current three-year-old can be seen carrying around We Are Water Protectors (Lindstrom & Goade, 2020) while exclaiming, “Take courage!” as we learn about the dangers of the Keystone Pipeline.

Young people across the world are leading the movement on climate change, and we can rise to this opportunity to help develop scientifically literate young citizens who make informed decisions that will bend the curve. Because climate change is a politically controversial issue, students will be bombarded with messages and claims about it on a daily basis. Without safe spaces in classrooms to explore these issues, students will be susceptible to misleading information. How many more times can we listen to young activists say they did not learn about climate change or the severity of its impacts in school? Collectively we can change this.

It’s not fun having to reflect on my own schooling experiences, but I know firsthand the power that teachers have in the classroom to elevate, affirm, and empower students’ ideas and identities. Because we have so much decision-making power over what takes place in the classroom, take time to explore your beliefs and values about teaching and learning. I firmly believe that, as educators, we have the power to teach science in ways we know will be more meaningful, equitable, and culturally relevant so that students will become the informed agents of change we need to take on the climate crisis. Our collective call to action can be amplified if we support, share, and learn from one another.