We’re fortunate here at Ten Strands to have a group of folks with a wide range of talents from different backgrounds, locations, and fields of experience. It makes for a strong team—and some very interesting staff meetings as, you can imagine, we each have our own perspective. The work we do has a lot of moving parts, and if you are a regular reader of our blog you’ve likely begun to discern how each part is integral to the whole.

I see Will’s comfort in the realm of big ideas and his talent at the ‘treetops’ level where he consistently highlights the importance of Ten Strands’ mission to the movers, shakers, and policy-makers. I observe Karen’s attention to detail, her ability to identify pathways linking educational standards, resources and instructional materials, and myriad learning strategies in ways that are helpful and meaningful to teachers and their students. I watch as Ariel consistently connects with people, making a strong case for our initiatives and speaking personally about how and why it matters. Our extended team of consultants is a formidable roster as well—but this isn’t a love fest, it’s a blog.

My part-in-this-whole is something like an information air traffic controller. I track things, like the outcomes of Will’s last meeting in Sacramento, the progress of the frameworks revision process, what the development team needs in order to reach grant-making organizations and individual donors, and where our program efforts like the San Mateo Environmental Learning Collaborative stand. I do my best to take in lots of information, organize it, synthesize it, and communicate it in ways that make sense to others so the Ten Strands vision that all people have the knowledge, awareness, and ability to make decisions that promote health and well-being for themselves and their communities one day becomes a reality.

That function was in high relief this week as I was asked by a 10S newcomer to explain what, exactly, is it that we really do. With all the acronyms, policy and ed-world jargon, different stakeholders, initiatives, and strategies it can seem really abstract, disjointed, and hard to sort through—and difficult to see how and where the real impact and positive change occurs. We’re dealing with big packets of information disguised as alphabet biscuits (EBE, EEI, STEM, NGSS, CCSS, LCAP, ELB) each with dizzying levels of details, backstories, tangents and trajectories. It’s easy to get lost in the minutia and lose sight of the big picture. What we really do, I explained, is make the case and a way for environment-based education in the California public K–12 space.

It’s really that simple.

The US defacto model of education, some assert, has not significantly changed since Horace Mann championed the Prussian common school model in the mid 1800s. Arguing that universal public education was the best way to turn the nation’s unruly children into disciplined, judicious republican citizens (and ensure that the children of poor immigrants got ‘civilized’, learned obedience and restraint, became good workers and refrained from contributing to social upheaval), he gained widespread middle-class (i.e.,caucasian male) support, and Massachusetts made education free—and compulsory—by state law. John Dewey’s Progressive Education theory, whereby the purpose of education was not so much the acquisition of a predetermined set of skills, but rather the realization of the student’s full potential and the ability to use those skills for the greater good, sparked discussion in the later 1800s through mid 1900s, but was not integrated in any concrete way into K–12 education.

So what?

The legacy of this model, and its seeming immutability, is that it can be confining and challenging as times change and it doesn’t allow much room for new learning goals and teaching methods to manifest easily. It leaves a lot of learners out in the proverbial (and literal) cold. Those called to the teaching profession often find themselves walking the tighrope in an attempt to create meaningful, real learning opportunities and experiences for kids while under pressure to conform to shifting standards and perform in ways measured largely by flawed standardized assessments. There is a fixation inherent in the system on quantitative data, but we’ve been cautioned by different voices over the years not to assume that only what is measurable is valuable (Plowden Report, 1967).

It’s complicated.

It doesn’t need to be.

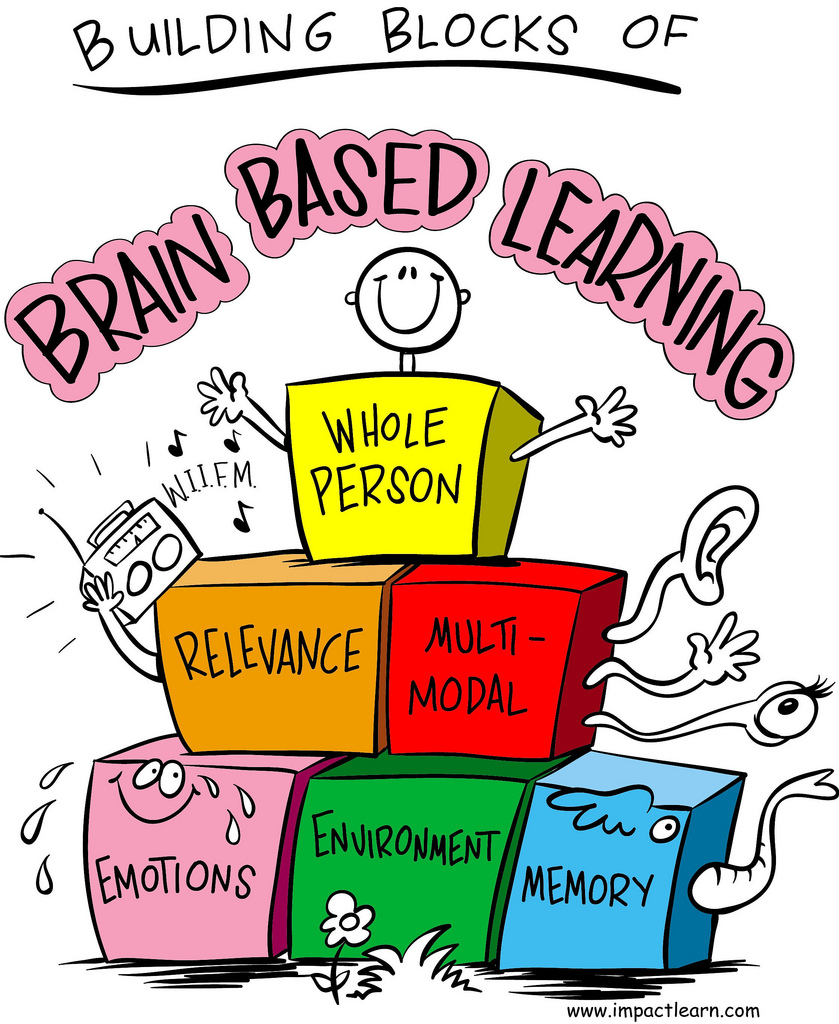

There is a strong movement toward student-centered learning. Recent research and scientific understanding around how the brain learns physiologically seem to support and explain the mechanics of what Jean Piaget expressed in his theory of cognative development: To Piaget, cognitive development was a progressive reorganization of mental processes as a result of biological maturation and environmental experience. Children construct an understanding of the world around them, and then experience discrepancies between what they already know and what they discover challenging them and expanding their reality.

If we’re not going to engage in an immediate exercise in reforming, restructuring, or straight-up revolutionizing K–12 education here in the states, we need to bridge some seriously enlarging chasms. We can build the bridge with high standards, learner-centered education practices, tools for teachers, customizable assessments—in other words, environment-based education. If California’s Local Control Funding Formula works like it’s supposed to (moving decision-making to the school district level and requiring community input) it could mark a significant shift back to communities having a greater voice in setting educational goals and accessing the means to achieve them.

Our perception of reality is intensely and intimately tied to our environment. It instructs us and shapes us from the moment we enter the world until that moment we depart it. It is the construct and the context that allows us to discern, discover, question, define, and grow. Our immediate environment—combined with capable and well-equipped guides and mentors—is the fundamental foundation of learning. There can be no capacity to comprehend ‘The Environment’ without first connecting in a conscious way to our own present surroundings.

So what does Ten Strands really do? We do our best to observe, listen, and understand the shifting landscape of education and the needs of teachers and students with an appreciation for and focus on the environment—the matrix that provides us with both an awareness of ourselves and a larger reality we experience together—so that as many California students as possible can learn from and connect to each other and this place we call home.

It’s simple, really.

(click on the image above for some stellar audio!)