More than a year ago, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the closure of traditional schools, residential outdoor science schools, and many other environmental education programs.

After the initial shock of having to shut down the outdoor science programs that I managed, I asked myself, “With decades of experience teaching outdoors, how can I help traditional classroom educators move education outside to make students and staff safer during the pandemic?”

The answers to that question led me to an innovative collaboration, interesting new areas of information, and a couple of unique projects.

As I developed resources for outdoor learning, I was introduced to a fellow advocate for outdoor learning environments at the Los Angeles County Office of Education, where I run the Outdoor & Marine Science Field Study unit.

LACOE facilities director Jema Estrella is a colleague whose work does not normally cross over into my area of environmental education. In an unusual cross-divisional collaboration at our large organization, she recruited me to be a part of a project to help schools envision and create outdoor learning spaces. She also enlisted the volunteer efforts of HMC Architects.

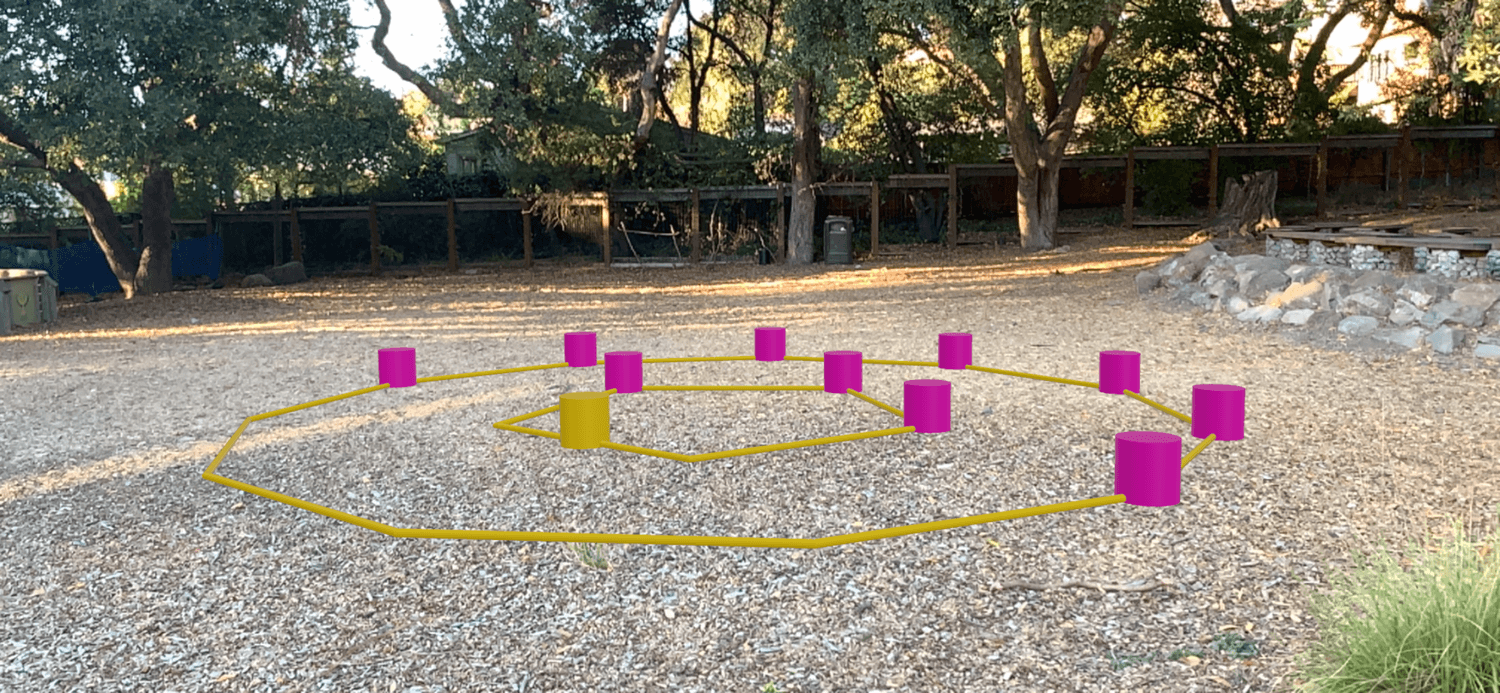

After collaborating on an outdoor learning spaces pilot project with a K—8 school, we eventually produced the Design Guidelines for Outdoor Learning Environments. These free guidelines are meant to be a resource for Los Angeles County schools for envisioning, developing, and using outdoor learning environments, but can also be used across various school settings in California and beyond.

As I gathered materials to support schools on outdoor learning in spring of 2020, I was directed to Green Schoolyards America for helpful information. The substantive National COVID-19 Outdoor Learning Initiative (NCOLI), cofounded by Green Schoolyards America, as well as Lawrence Hall of Science, San Mateo County Office of Education and Ten Strands, helped me gain more insight and resources to add to materials shared with schools. Their resource of photo examples was critical in my workshops as I helped others envision new possibilities for teaching and learning. NCOLI’s excellent resource of photographic examples was critical in my workshops as I helped others envision new possibilities for outdoor teaching and learning.

While the other collaborators on the Design Guidelines for Outdoor Learning Environments project focused on design elements of outdoor learning environments, I focused on the educational aspects of how to maximize the assets found in outdoor spaces.

For me, the educational dimension of outdoor learning begins with acknowledging and understanding the differences between indoor and outdoor learning, which require different approaches.

CHANGING MINDSETS

An essential step in creating significant and lasting change involving a group of people is getting the support of those involved.

Getting educators to support and actually use outdoor spaces can be a very significant shift. I believe the key to gaining support for any change is building trust through sincere listening and addressing concerns and fears as early as possible.

Given enough time, most of us can come up with convincing arguments as to why a proposed change is a bad idea. Experience has shown me that it’s always better to address concerns earlier, before arguments and fears build. We have to remember that most of us are uncomfortable with the unknown. Having a positive experience with a new situation as soon as possible can go a long way in convincing people that change is good. In that way, educators creating new outdoor learning environments or practices will benefit from early strategies of recruiting support.

DIFFERENT AMOUNTS AND TYPES OF PHENOMENA

There are often radically different amounts and types of phenomena — observable things or events in the universe — available for the teaching and learning process.

Many indoor educators consider the phenomena in the outside world to be distractions that can only detract from the process of education. However, being a science educator, I view natural phenomena as the necessary ingredient that makes education meaningful!

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and our more recent understanding of science education put phenomena at the very center of effective lessons. Another way to frame this contrast is that some educators may think there are too many distractions outdoors, while others might see inside environments as too sterile and lacking the quantity or quality of natural phenomena to help students fully integrate science concepts.

I have found that outdoors an educator must help students focus amid all the phenomena, whereas inside conditions require the addition of phenomena to make lessons effective. For example, if a teacher is teaching inside about differential heating, that teacher could set up a light to shine on several surfaces to have students understand or make predictions about this phenomenon.

However, if the teacher took students outside to observe that same phenomena on the school grounds, students could observe that phenomena in context. They may even gain an understanding of the thermal mass of concrete that you hadn’t planned on!

INSIDE LESSONS OUTSIDE VERSUS PHENOMENA-CENTERED APPROACH

Embracing the natural phenomena found outdoors leads to two strategies for teaching outside: inside lessons taught outdoors, or intentionally using phenomena available.

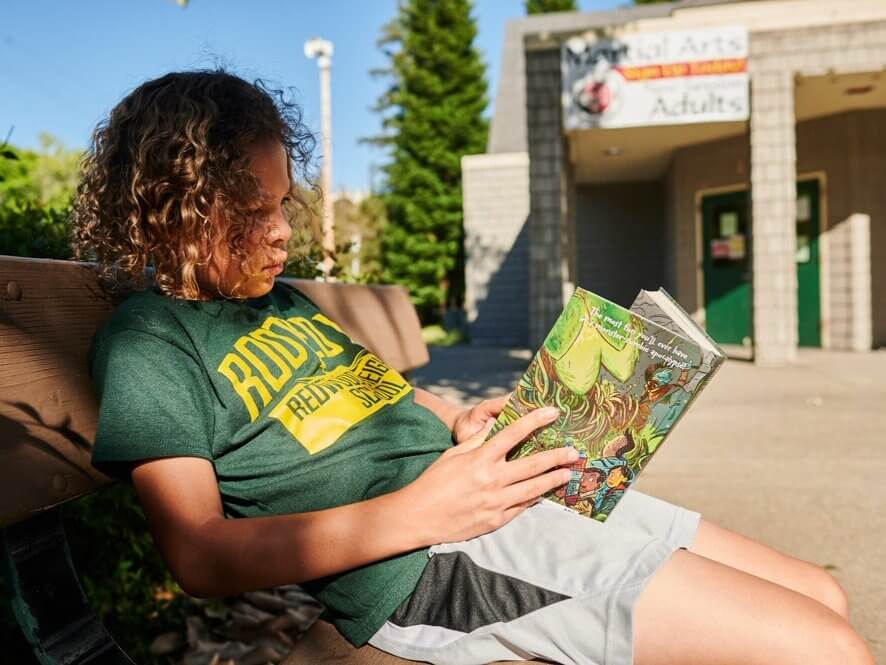

Recent and historical accounts have shown that traditional inside lessons are possible to teach outside in reasonable conditions. For example, I’ve used this traditional lesson approach, having students complete word puzzles outside when they seem to need a refocus.

The other approach is to intentionally use and anchor lessons on the phenomena available in outdoor settings, such as having students make observations and drawings of plants to explore and explain plant adaptations.

While this strategy is usually highly engaging for students, it requires significant flexibility from the educator. If you are planning a lesson around gravity, that phenomena will reliably be present inside or outside. However, if you want to teach about butterflies or sound mapping using bird calls or any other ephemeral phenomena, there will be many times of the day and year when there will be none available.

The ability to pivot as unique or interesting phenomena become available is essential to excellent teaching outside. The skill of pivoting to integrate new or unplanned phenomena into a lesson does take practice to master but can be learned. The first step in learning that pivot is valuing the potential lessons and excitement of new phenomena.

PHENOMENA IN CONTEXT

Outside learning environments, particularly functioning ecosystems, can provide not only rich phenomena but also a context full of related information about that phenomena. That context provides the clues that help us unravel the mystery of whatever we are exploring with science.

A real-life example might happen when discovering an unusual rock in an ecosystem. To figure out what it is, we first look around to see if it matches the bedrock or other rocks in the area. We also might wonder how it got there and compare its rounded or angular edges to other rocks or landforms nearby.

The context provides so many of the answers when we seek to understand things in nature. Realistically, could a schoolyard provide enough clues in our process of discovery to help learning? Maybe.

Unfortunately, cohesive ecosystems on or adjacent to schoolyards are extremely rare. However, even the most developed of urban schoolyards can often provide additional information as we investigate.

In the most sterile of environments nature inevitably creeps in giving learners and educators more opportunities to explore. Even if the environment is a schoolyard, the sun will still cast shadows, and the weeds will push through the cracks in the concrete to provide an opportunity for wonder.

PHENOMENA IS GOOD FOR MORE THAN SCIENCE

Having students make detailed observations is an essential step in science but can also be key to refining Language Arts skills. Exploring outside phenomena can be integrated into poetry, map making, creating visual arts, music, understanding geometry, storytelling, and much more.

Not only are opportunities everywhere for utilizing outdoor phenomena in most areas of education, but phenomena are also the very ingredients that can make learning more profound.

ADVERSITY AND CREATIVITY

Going outside often involves adverse conditions. The Design Guidelines for Outdoor Learning Environments include discussions of the logistics to address weather and difficult conditions.

After 30 years of teaching science outside, I admit that there are some days, rare in California, that inside is safer and better for learning. At the same time, facing adversity and responding to it is vital to learning and social-emotional development. I’m fond of saying that adversity can often ignite our greatest accomplishments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought tragic and often insurmountable adversity to many. For those of us lucky enough to survive, that adversity forced us to find solutions to huge obstacles and reexamine almost every aspect of our lives, including education.

Amid the massive social upheaval resulting from the pandemic, many creative ideas have emerged. A few of those ideas are worth keeping. The benefits of outdoor learning are some of those gems I hope we can embrace and cherish.

One Response

Thanks, Shaun! What a great piece. It makes so much sense, seems that the return on investment is so great in so many spheres from health to wellness to connection to nature to LEARNING, why is the uptake in (other) districts so slow?