When I think of environmental literacy as a kinder[garten] teacher, I carefully look at how I will provide my students with a strong base to feel comfortable exploring their environment to not only gain an appreciation of their surroundings, but to understand the crucial role they play in caring for it.

So said one of the teachers attending our 2018 Alameda Elementary Environmental Literacy (AEEL) summer institute this past June. The AEEL project is a three-year environmental literacy professional learning program for teachers that was created by the Bay Area Science Project and the University of California, Berkeley Natural History Museums with support from Ten Strands, the Lawrence Hall of Science, and the Alameda Unified School District. We think the words of this teacher capture the essence of what we are trying to do: support K–5 teachers to engage their students in Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) three-dimensional learning about the environment, and help students build a relationship with the natural environment through outdoor inquiry experiences. What do teachers need to accomplish this? They have to be comfortable taking their students outdoors for learning activities. They also have to know how to integrate outdoor learning with curricular goals in science and social studies as well as language arts and math. And they have to be confident in their knowledge of environmental science and local environments. Our professional learning model brings together science pedagogy expertise, teacher leaders, and scientists in a collaboration to develop and present activities that offer substantive content and strong learning experiences to help teachers achieve these goals.

At our inaugural summer institute in 2017, we emphasized outdoor learning and exploration of life science themes by investigating local habitats and biodiversity, and considered their value to humans along with our role in protecting and conserving them. The 2018 summer institute had an earth science focus, exploring earth system interactions, water, weather, and global warming. Our activities targeted a selection of NGSS core ideas that are appropriate for elementary students and are foundational for understanding local environmental phenomena and challenges. It is also especially important at the elementary level to build knowledge about environmental problems without leaving students feeling helpless or scared. For this reason, AEEL activities are focused on the natural processes that underlie understanding of environmental challenges, and on the positive actions that people can do to care for the environment. Each summer institute day-long session included time outdoors observing earth science processes in the schoolyard, neighborhood, local parks, and nature areas. Our investigations were framed by a pair of questions; one directed at a basic science component and a related question based on the Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs). Our teacher-leaders also presented related grade level environmental science lessons from Alameda’s science curriculum, modelling literacy strategies, data analysis and sense-making strategies, building in an outdoor component, and highlighting EP&Cs connections.

On the first day we worked on earth systems and their interactions asking, “What are some of the interactions among earth systems?” and “How do earth systems provide resources for humans and other living things?” A 20-minute morning walk around the schoolyard gathering observations was the basis for developing the vocabulary of earth systems (atmosphere, hydrosphere, geosphere, and biosphere). Deeper investigation of system interactions followed with a water cycle simulation game and an EP&Cs-based activity exploring how different earth systems provide resources for everyday man-made products, and grade level lessons on earth materials and weather. Our University of California (UC) scientists wrapped up with a content presentation about earth systems and how scientists study them.

On the second day we asked, “How does water affect the landscape?” and “How do erosion and deposition affect human habitats and resources?” Teachers explored the effects of water on landscapes with stream table experiments run outdoors, and then walked to the local beach to look for examples of earth system interactions and erosion of all kinds in a local environment. Our scientist talk this day covered how erosion and deposition by wind and water have shaped the San Francisco Bay and Alameda Island. Themes of wind and soil were further explored by teacher-leaders in grade level breakouts in the afternoon.

On the middle day of our summer institute we held a one-day workshop to which all Alameda Unified teachers were invited (not just the summer institute participants). The themes for this day were environmental literacy, inclusion, and tools for connecting with nature. The morning keynote speaker was Jose González, the founder of Latino Outdoors. His inspirational presentation included an interactive session in which we explored cultural perspectives, interpretations, and relationships to nature, including ways to view and study nature as a means to engage with diversity, equity, and inclusion—and vice versa. He offered a number of tools for supporting students and personal identity in relation to place, using nature as a grounding space for learning and connecting cultural identity to nature. He reminded us to bring magic and wonder and emotional connections to our explorations of nature, and to be open to all our students’ personal stories.

This keynote session was followed by a field experience on nature journaling as a tool for science learning, led by naturalist educators John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren. The question for this part of the day was, “How can field and nature journaling contribute to, and support, environmental literacy for all students?” Participants were guided through a series of fun and eye-opening activities for engaging students in the exploration of local natural phenomena, and a means for expressing individual perspectives. We learned a variety of journaling techniques in combination with NGSS science practices and cross-cutting concepts that will help students develop skills for observation and interpretation of the environment. The energy and knowledge of leaders was wonderful. One catchy and useful strategy they offered for any student of natural science was to make observations on the other side of done–in other words, when you have the feeling that you are finished observing, of being done, look some more!

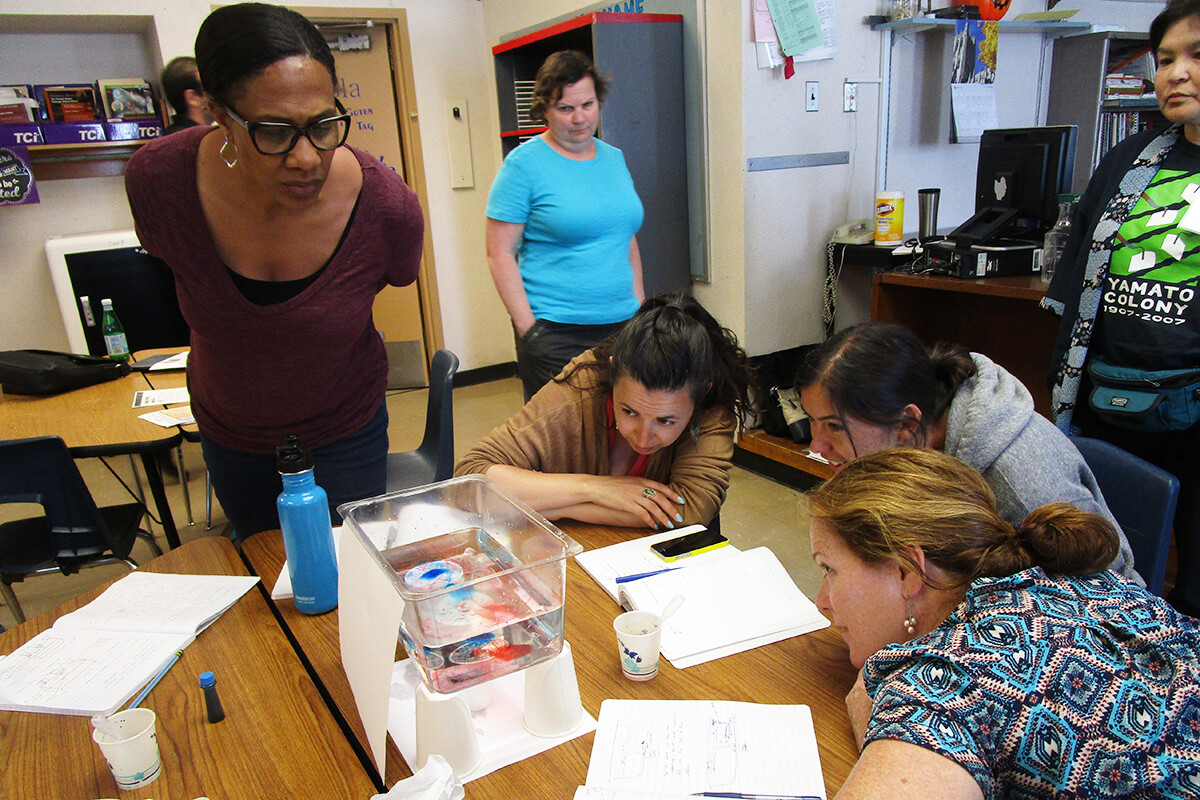

We continued our exploration of earth science on day four, moving to processes in the atmosphere, i.e. weather! Our theme questions were, “How does water move in the atmosphere? How is weather a distributor of resources? Why is it valuable to be able to predict weather?” We started with outdoor observations of the atmosphere in the school yard. Next, we explored and modeled condensation and convection in the classroom, leading ultimately to the building of a conceptual model of fog formation and movement in the Bay Area. After exploring the phenomenon of fog we turned to a human consideration and explored historical accounts of the effect of weather on agriculture.

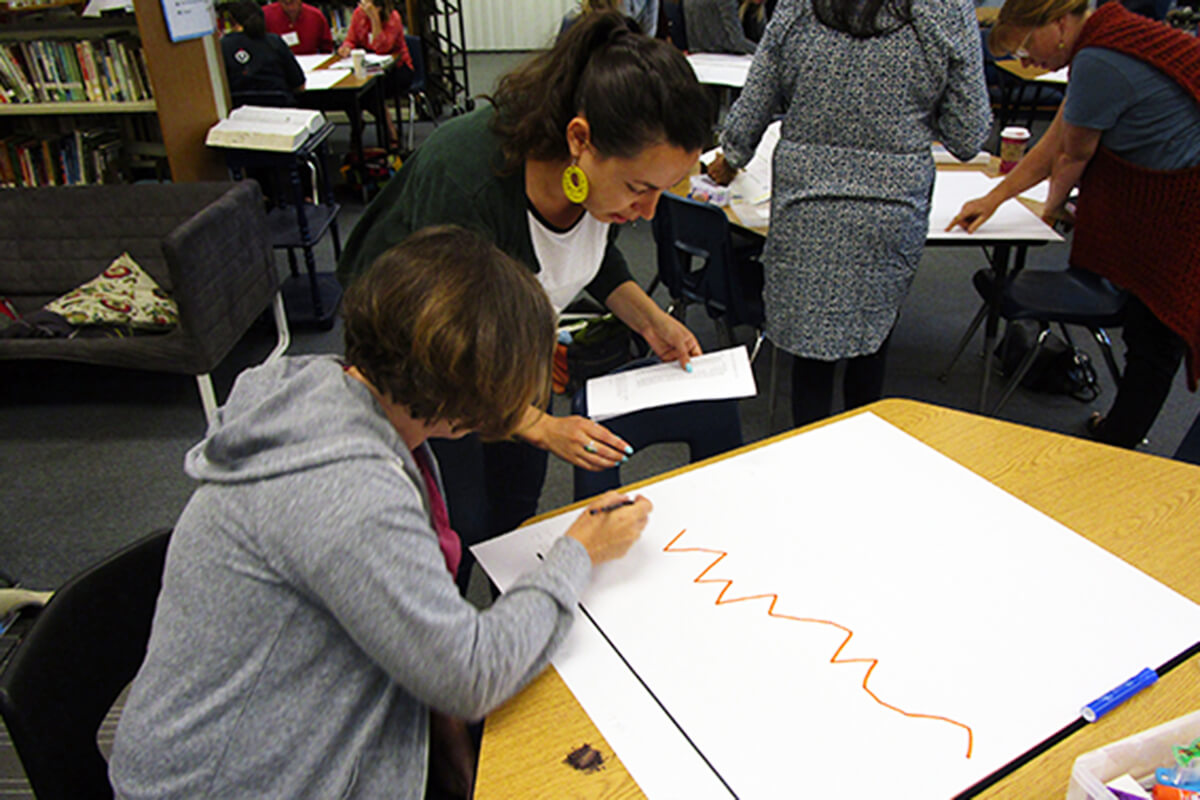

On day five we turned to a topic on everyone’s mind: global warming. Our questions were, “How does global warming work?” and “What can we do as individuals and as a community to reduce global warming and its impacts?” We started by looking at global temperature and CO2 data from 1850 to the present and searched for patterns. Small groups of teachers each received a 20-year increment of global temperature data and CO2 levels to plot on individual panels with pre-made axes. Once each group had plotted its data we assembled all the panels, taping them to a wall in the schoolyard to form a 20-foot wide graph showing the continuing increases in both temperature and CO2. A lively discussion ensued as we explored the trends, asked questions, and interpreted the data together.

But, while the association between temperature and CO2 is strong, it is only a correlation. How could this relationship be further explored? One way is to learn about the mechanism that links temperature increase to CO2—the greenhouse effect. We did this with an energetic simulation game called Greenhouse Gas Tag. This simulation shows how the greenhouse effect works to keep the earth warm enough to support life, and also how it causes global warming when there is too much greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. Armed with knowledge of the pattern of temperature and CO2 rise, and the mechanism connecting the two, teachers made and shared conceptual models of global warming and were ready for a content presentation by our UC scientists about the causes and effects of CO2 increases and human actions and policy that begin to address the problem. This led us into a jigsaw discussion of a variety of graphs and readings about the positive steps people are taking to try to stem global warming. Such a discussion in an elementary classroom would build knowledge about environmental issues that is empowering to young students, leaving them hopeful and confident.

It was a fun and action-filled week of outdoor learning, science content, and thinking about the relationships between humans and the environment. Are our participating teachers going back to their K–5 classrooms ready to teach environmental literacy that integrates science, language arts, outdoor learning, and the EP&Cs? Are they more confident going outside? Our survey suggests that they are—the teachers’ average self-rating of confidence increased in all areas (e.g., teaching with outdoor inquiry, using the EP&Cs, integrating literacy in science, better understanding of environmental literacy). An example of teachers appreciating the power of taking students outside can be seen in this comment from the post-survey:

Outdoor learning experiences are energizing. Students return to class ready to report, write, and share.

Another teacher beautifully articulated her understanding of the integrative nature of environmental literacy in this remark:

What is environmental literacy? Knowing how land, sea, air, sky, atmosphere, and water are related, knowing and learning what can be done by people to keep our homes, habitats, regions, and the world healthy and thriving.

Going forward, we will meet with these K–5 teachers again for a school year follow-up and another summer institute. There we can revisit how they are implementing their learning, and we can continue working together to make the environment a central theme in science, language, and social studies teaching. If their enthusiasm and diligence at this past summer institute is a sign of what these teachers are bringing to their students this school year, we can feel very hopeful about environmental literacy for students becoming a reality.