It is a beautiful Friday morning in May when Ten Strands team members Karen Cowe, Ariel Whitson, Mike Howe, and I arrive at Dixie Elementary School in San Rafael, California. After gathering in front of the school’s jungle gym playground, we head to the front office, where we are instructed to sign-in and choose one of a variety of visitor identification badges. Mine is purple and depicts a smiling koala bear.

After donning our badges, we head to a nearby building where we are told we can find Debra DiBenedetto’s second grade classroom. Debra has invited us to meet with her this morning and observe one of her lessons on environmental restoration. When we arrive, Debra greets us with enthusiasm and warmth, and directs us to the front of the creatively and colorfully decorated room. One by one we introduce ourselves: we are from Scotland, California, Arizona, and Virginia—and we are here to see the Dixie Outdoor Classroom.

Located on the banks of Miller Creek, just a short walk away from the school buildings, the Dixie Outdoor Classroom is a space nestled amongst tall green trees and shrubbery where students are able to learn about the environment in a natural setting. The outdoor classroom is home to numerous native California plants, such as Sneezeweed and California Wild Rose, and contains benches arranged in a semi-circle where students can sit.

After we introduce ourselves, Debra asks her students to tell us what they do in the outdoor classroom. The students take turns speaking: “We learn about the creek and how it changes,” “We help animals and plants,” “We help animals and plants because they give off oxygen,” “We pull invasive plants.” Her students are energetic and enthusiastic, and I am excited to see the outdoor classroom for myself.

Just beyond the compost tumbler and a blacktop painted with an outline of the United States, we find the path down to the creek. After we walk down the path and the students take their seats on the benches, Debra tells everyone that they will be split into groups. One group will go down to the creek and use small collection bins to pan the creek for bugs to observe and identify, and the other group will be planting native iris and buckeye. Each group will get a chance to do both activities.

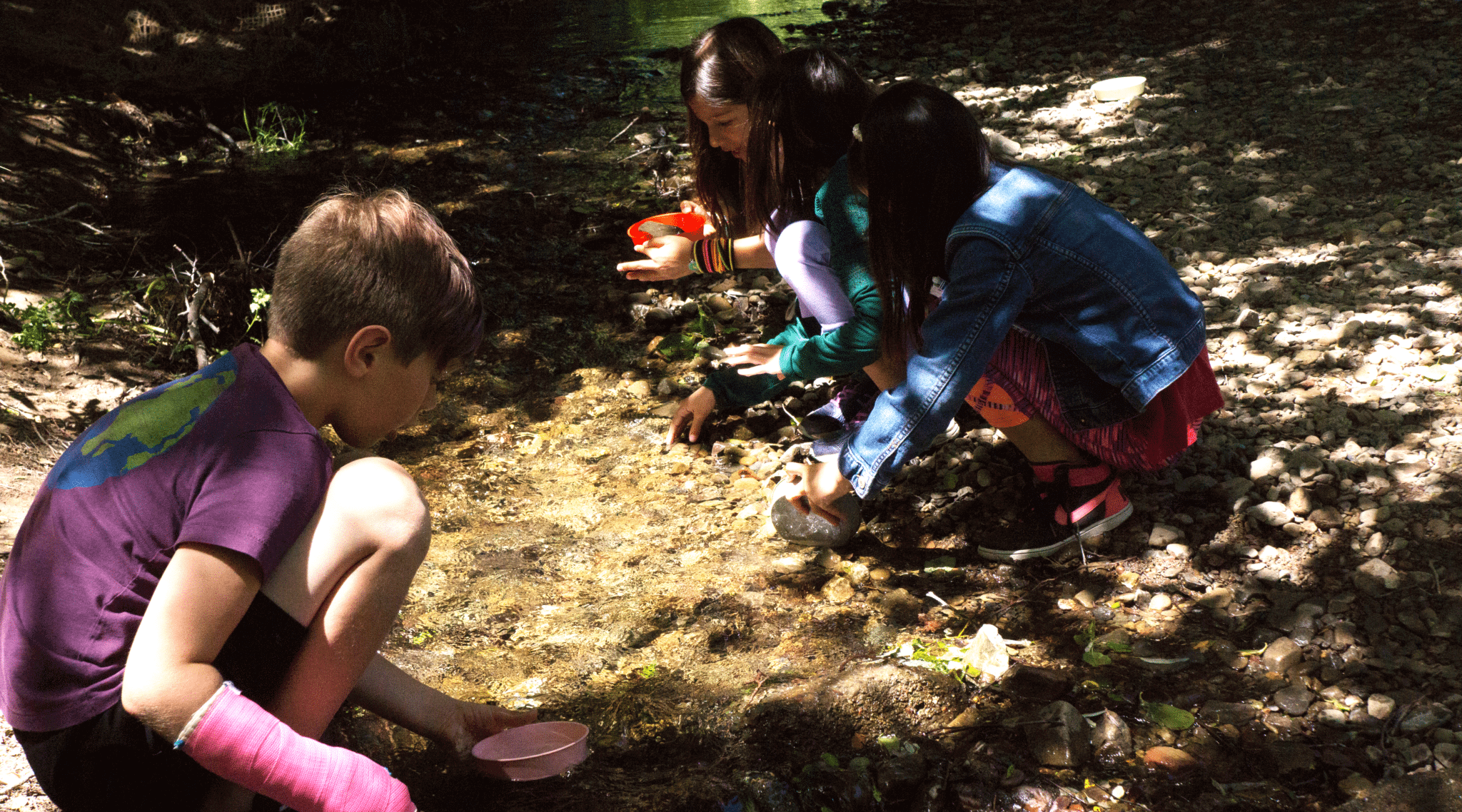

As I join the students studying the creek, I hear “I found a fly!” and “I want to find a water skater!” While listening to Debra give instructions to the planting group, I envision the planting process Debra describes: first dig the hole, then measure the hole’s width using the “palm test”, massage the plant to gently remove it from its casing, add water to the hole, place the plant in the hole, and re-cover it with soil. I listen as one student reflects on a past experience of using too much water. In passing, I also overhear another student tell Karen about the activities, “We planted iris and saw a lady bug.”

Walking between the two groups, I am struck by how much the students are enjoying themselves and how much they are fully immersed in what they are doing. At the creek, I see the students teaming up to help each other search for insects. They share in each other’s enthusiasm when one student finds something, and it is a group effort to figure out exactly what they discovered. What is the shape of the bug? What does its thorax look like? Does it have wings? The students help each other sort through their insect identification materials, and return their discoveries back to the water when they are done.

Walking between the two groups, I am struck by how much the students are enjoying themselves and how much they are fully immersed in what they are doing. At the creek, I see the students teaming up to help each other search for insects. They share in each other’s enthusiasm when one student finds something, and it is a group effort to figure out exactly what they discovered. What is the shape of the bug? What does its thorax look like? Does it have wings? The students help each other sort through their insect identification materials, and return their discoveries back to the water when they are done.

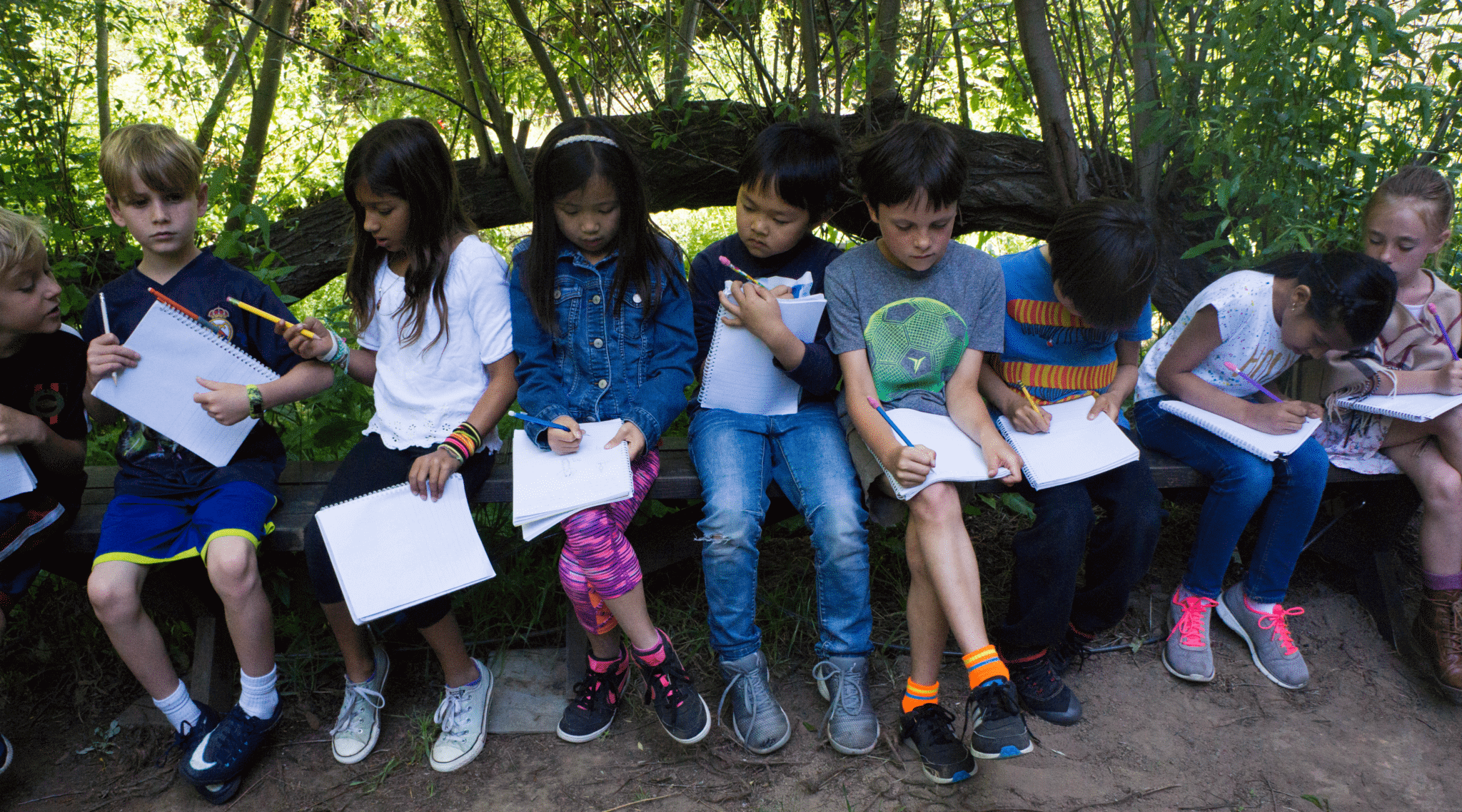

At the top of the path, I observe the students diligently digging and measuring their holes and planting their California natives. The students work in pairs, one shovel and one plant between them, and collaborate with one another to sort through the planting process. There are only a couple of watering cans for all the students to use, but they help one another by passing the cans around so that each pair gets a chance to complete the project. After everyone has finished, Debra instructs the students to return their shovels to the top of the path, take out their journals, and write about what they have planted. I see books opening, pencils scribbling, and students whispering to make sure what they have written is correct.

As class time comes to a close, Debra collects everyone at the benches. She asks her students to reflect on what they learned from the day’s activities and what they noticed about the creek in particular. What were the changes since the last time they visited? Is the creek narrower or wider? What about the current? Where is it moving most quickly or slowly? The students reflect on their learning quietly and aloud, and after everyone has finished writing in their journals, they are dismissed to recess.

Later, as we talk to Debra about her work, one of her comments stands out to me: the outdoor classroom “makes science and learning about the environment engaging and real to students, whereas otherwise it could be intimidating or negative.” Being outdoors and engaging with the environment allows students to exercise and grow their critical and creative thinking skills, and learn how to collaborate with one another to solve problems and complete assignments. By interacting with nature and their own environment, students can begin to understand the world around them, how they fit in, and how they can make an impact.

Through hands-on, fun, environment-based learning, Debra DiBenedetto is using the Dixie Outdoor Classroom to teach her students about restoration, the importance of protecting native species, and about the joy that comes from being an environmental steward. As the newest member of the Ten Strands team, I believe in the importance of environmental responsibility and bringing environmental literacy learning opportunities to students, so this ‘field trip’ to the Dixie Outdoor Classroom was especially enjoyable. I was delighted to see the Dixie elementary schoolers interacting and connecting with nature in an outdoor space near where they live and learn. Thank you for having us, Dixie students and Debra—and keep up the great work!