Walking along the shoulder of a busy two-lane thoroughfare called Green Valley Road to Pinto Lake on a sunny morning in Watsonville, CA, bringing up the back of a line of 3rd grade students from Amesti Elementary School, I am reflecting on how aptly the road is named when Juan—everybody calls him ‘Jay’— says, ‘There’s too much trash on the ground all the time. Why do people just throw it on the ground? We need to clean this up!’ He starts picking up every plastic bottle, shredded bag, and bit of ravaged cardboard we pass. ‘Wanna help me?’

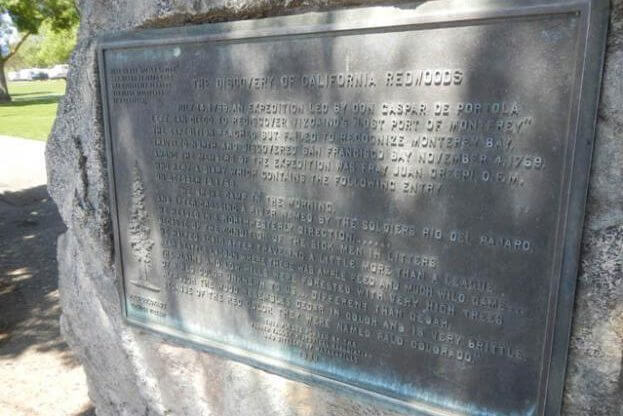

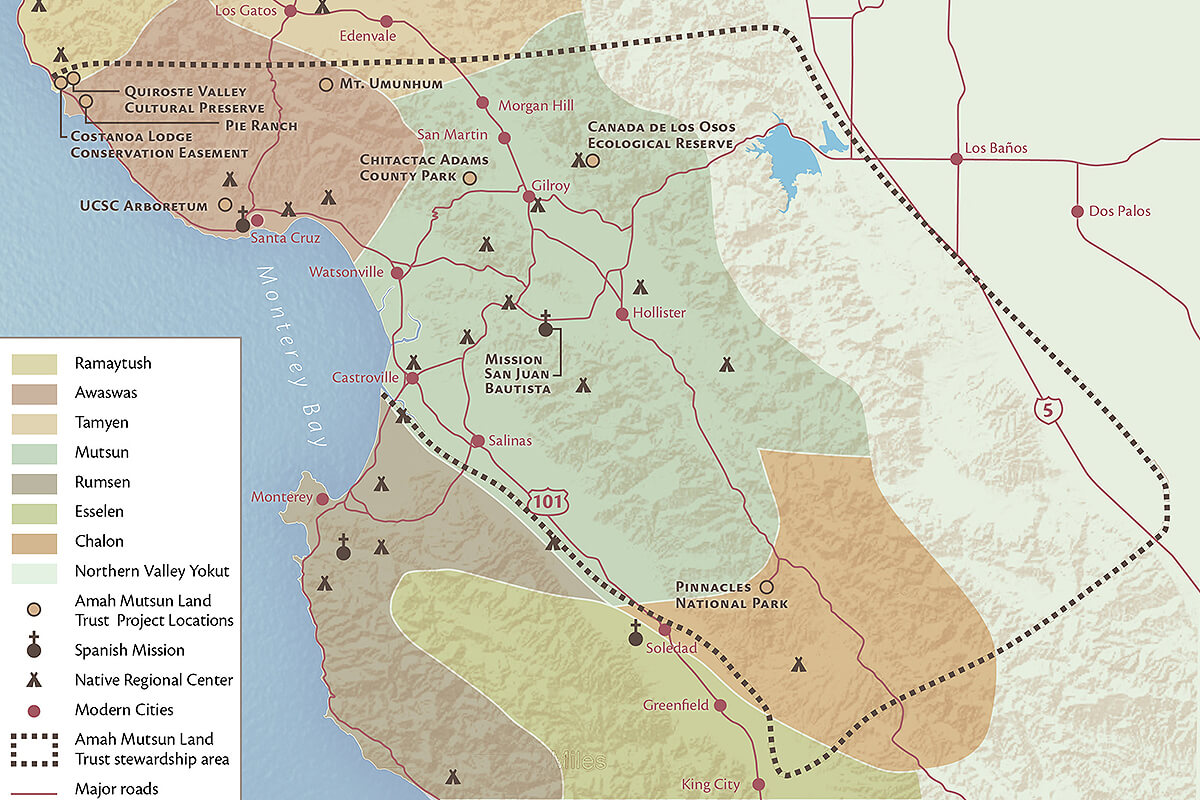

The Pajaro Valley has a multicultural history rooted in the land. Humans have lived in this valley for more than 10,000 years—Indigenous North Americans, Spanish colonists, Californios, Yankees from the east coast, freed African American slaves, Irish, Chinese, Danish, Portuguese, Japanese, French, Italian, German, Slavic, Filipino, Mexican, South American, and Canadian immigrants have all called it home. Watsonville sits in the middle of the Pajaro Valley in the floodplain of the Pajaro River, just south of Santa Cruz and slightly inland from Monterey Bay. Before colonization it was a central point of cultural convergence for the people collectively known today as Ohlone—here, the Amah Mutsun—spread throughout at least nine villages. Every seven years, the Condor Ceremony was held at the mouth of the Pajaro River to honor the dead; it was during one of these ceremonies in the 1700s that the Spaniards in the Portola Expedition arrived and saw a large straw-stuffed bird (pajaro) as they crossed the river. Sometime around October 10, 1769, they became the first Europeans to see a Coast Redwood tree: a bronze plaque at Pinto Lake commemorates the event.

The place that is today known as Watsonville was part of a Mexican land grant made to Sebastian Rodríguez in 1837. In 1847, a second wave of Europeans arrived, forty of whom settled to tend animals and crops. In 1848, the California gold rush began. Migrants from the American east poured in to try their luck in the Sierras, along with wealthy speculators who purchased land for low prices, acquiring acres of property in the valleys. Farming and ranching began to further shape the economy of the area, defining it to this day. In 1851, Judge John H. Watson arrived in the Pajaro Valley, alleging a claim to some of Sebastian Rodríguez’s property and he laid out a township near the Pajaro River. Watson ultimately lost his claim against the Rodríguez family, and in 1862 he left Watsonville and moved to Nevada, never to return.

A cascade of internal reflexive thoughts overlap in a chorus of—I should probably keep this kid with the rest of his class, and There’s way too much trash to do anything about it, and It’s pointless because people are not gonna stop throwing crap out of their cars anyway, and It’s hopeless—it’s not going to make a difference. I understand the collective failings of adulthood and our society in that moment, and say, ‘Sure. Let’s carry as much as we can. But we shouldn’t get too far behind the others.’

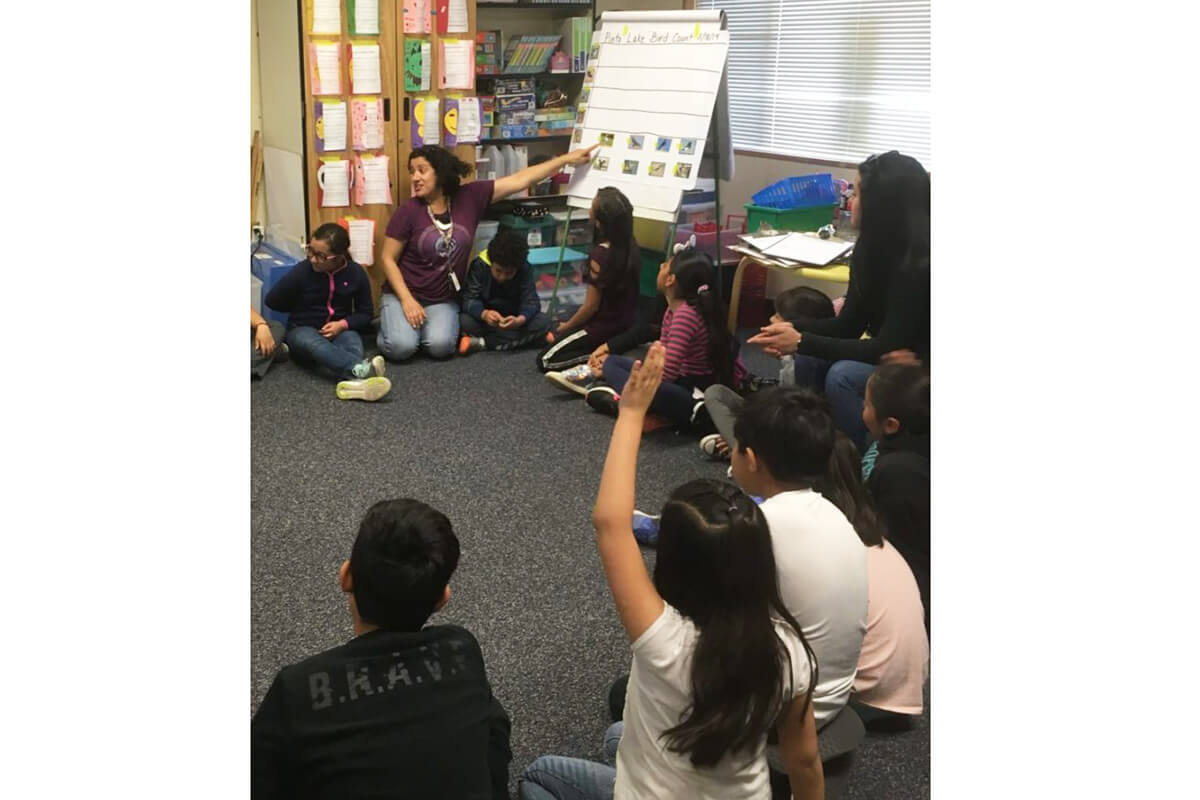

Pajaro Valley Unified School District (PVUSD) has 16 elementary schools, five middle schools, one junior high, and three high schools serving more than 30,000 students. Districtwide, 81% of PVUSD students are Latinx, 42% are English language learners, and in Watsonville 30% of those under 18 are living below the federal poverty line. At Amesti, there are 577 students, 94% of whom are Latinx; 70% are English language learners. Julie Vallens’s class is an energetic and purposeful group of seven- and eight-year olds who have spent the morning reviewing weeks of classroom science lessons in preparation for their walking field trip to Pinto Lake Park.

I join their classroom circle and learn from them about the birds that call Pinto Lake home; their names, what they eat, the sounds they make, and which ones each student is most hoping to see.

I learn from Corina, a young classroom aide, that she is supporting several students in Julie’s class as part of PVUSD’s wraparound programs, which provide focused services to the children of migrant working families in the district. Corina grew up here—she is the daughter of migrant parents—and she tells me that she wants to stay in Watsonville and serve her community by providing the services that she wishes had been available to her when she was a student in the district.

Watsonville’s story is told through the land, through the crops farmed in the surrounding fields, and by the waves of immigrant communities who worked the land—European immigrants in the 1800s, followed by waves of Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino immigrants at the turn of the 20th century through World War II. It wasn’t until the end of the Bracero program in the 1960s, and its residual impact, that migrant Mexican farm workers reunited their families and settled down here. Watsonville’s history includes an unbroken tradition of unflinching community and labor activism among the city’s working class, spanning Depression-era migrant workers walking off the fields to the 1985 cannery strikes, which were led and propelled predominantly by Mexicana & Chicana women in the community.

The morning sun is hot, and as the cars and trucks pass us their size and speed generate gusts of fossil fuel-fragranced wind. There is no sidewalk, but the students have been properly prepared by Julie and are walking safely in their single-file formation. They don’t seem at all scared. Jay and I have our arms full of discarded debris at three minutes into our seven-minute walk. ‘I don’t know how much more we can carry,’ I tell him. A second student, Edwin, who has been walking more slowly than the others because of his asthma, says, ‘I’ll help,’ and joins the effort.

At the Monterey Bay Aquarium (MBA) in 2006, vice president of education Rita Bell was participating in internal conversations centered around new ways of fulfilling their mission to inspire conservation of the ocean. Understanding that the diversity of their immediate community was not reflected in those who visited MBA, they began to discuss ways to widen the MBA community to be more inviting and inclusive.

They initiated face-to-face outreach to different communities they hoped to engage around this issue, taking the position of co-learners—listening and learning lessons directly from community members about how the aquarium could be more welcoming and culturally relevant.

Alongside this process, the idea emerged that working with a local school district to impact science content taught in classrooms would reach a large number of students equitably, and that what those students learned would transfer to their wider communities. After enlisting external support to research and identify potential partner districts, PVUSD was chosen. They began working with PVUSD’s newest high school, which had an intentional focus on environmental learning, to develop the Watsonville Area Teens Conserving Habitat program, linked to the school’s honors biology class. Their work with PVUSD evolved to include middle- and elementary-level students.

By 2009 MBA was coordinating with the district to provide professional learning centered in science and focused on the local environment, and prioritizing PVUSD teachers.

Simultaneously, Amity Sandage had been working in Santa Cruz County conducting surveys, mapping, and convening local nonformal providers of K–12 environmental education as a California Regional Environmental Education Community (CREEC) regional coordinator. Working part-time at the Santa Cruz County Office of Education under then-superintendent Michael Watkins, who saw the value of expanding student access to impactful, hands-on learning experiences in the local environment, she worked with providers to create Monterey Bay Environmental Educators (MBEE)—an organization supporting collaboration and consistency among providers, and quality of resources for the area’s K–12 teachers and students. Then, in 2013, a few things happened. The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) happened. And just before that, Rob Hoffman happened.

We are halfway to Pinto Lake, having been joined by Sebastian and Fabian. I can still see the rest of the class, so I’m feeling ok about my unconventional chaperoning. The students call me ‘teacher’—by this time I have assimilated the understanding that this is their word for any adult who shows up in the context of school and interacts with them. I do my best to accept it as the honest gesture it is, ignoring my urge to correct them—because teachers do SO MUCH and how can I claim an identity I have not earned? All sets of arms are now at capacity with the trash we’ve gathered. ‘I don’t think we can carry any more,’ I tell them. As the last syllable leaves my mouth I see it: a blob of black plastic, larger than the rest, caught in the branches of some roadside scrub. Jay and I make eye contact; he sees it too. ‘’Una balsa grande,’ I say grinning, tilting my chin toward it. ‘And a REALLY big one!’ he replies. His face breaks into a smile wide as the sky and bright as the morning sun. I ponder the physics of deus-ex-machina as we empty our arms of all we’ve been carrying into the singularity.

NGSS explicitly calls for teaching science in new ways. It also specifically includes the environment in a way that surpasses the content traditionally taught in the geological and earth sciences. The opportunities provided by this shift have been key to ongoing work around environmental literacy that Ten Strands, the California Department of Education, CalRecycle, the California Environmental Literacy Initiative (CAELI), and others have undertaken. When Rob Hoffman moved into the roll of PVUSD’s district science coach pre-NGSS, he connected quickly with the work that MBA and MBEE were doing with teachers and students.

He also made the connection between math, English language arts, and science—a strategy that held particular relevance and positive impact for the population of students he serves.

Working with MBA and community-based partners (like the Watsonville Environmental Resource Center), project-based science institutes, a Literacy in Science Series, and teacher-led teams prioritized professional learning for PVUSD teachers. After NGSS was adopted in 2013, Rob envisioned another opportunity: an NGSS-focused steering committee that would pull together the current community partners (MBEE, MBA, and others), professional learning, and relevant place-based hands-on student learning experiences into a cohesive, districtwide environmental literacy plan that would formally articulate PVUSD’s science goals—and the strategies to meet them. Rob moved into the Science & CTE Coordinator position, and ChangeScale soon took notice.

We make it to Pinto Lake Park with our mostly-full bag. I’m relieved that we’re not late for the circle, where pencils and clipboards with a list of birds and room for observational notes are being distributed. Jay and the others are proud of the bag’s girth and weight; their classmates are asking questions, and as we break into our designated groups of exploratory scientific data collectors it becomes apparent that the students have unanimously made an unspoken, unauthorized addition to their assigned activity. Besides observing and taking notes about the lake and its inhabitants, they are collecting the litter they find on the ground. An elder already fishing at the lake notices—I see him observing, unnoticed by the students. Shortly thereafter, a park employee provides a few more large black bags.

ChangeScale was founded as a collaborative of nonformal environmental education providers in 2011 to build cohesiveness, effectiveness, and prominence in the field of environmental education in the San Francisco and Monterey Bay regions.

Their goals include building capacity for quality, relevance, effectiveness, and increased access to environmental education for all students.

ChangeScale member organizations, along with other stakeholders across California, were instrumental in the creation of former State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson’s Blueprint for Environmental Literacy, and served on California’s Environmental Literacy Task force (CAELI’s predecessor). At Amity’s suggestion, Rob Hoffman applied on behalf of PVUSD to ChangeScale’s School Partnership Initiative for Environmental Literacy, and Pajaro was selected to join the first cohort to build out districtwide environmental literacy plans. The work that Rita Bell (MBA), Amity Sandage (CREEC/MBEE), Michael Watkins (SCCoE), Rob, and the teachers and community partners had done was unique, inspired, and strategic: there was clearly capacity for long-term sustainability and success, and ChangeScale recognized this.

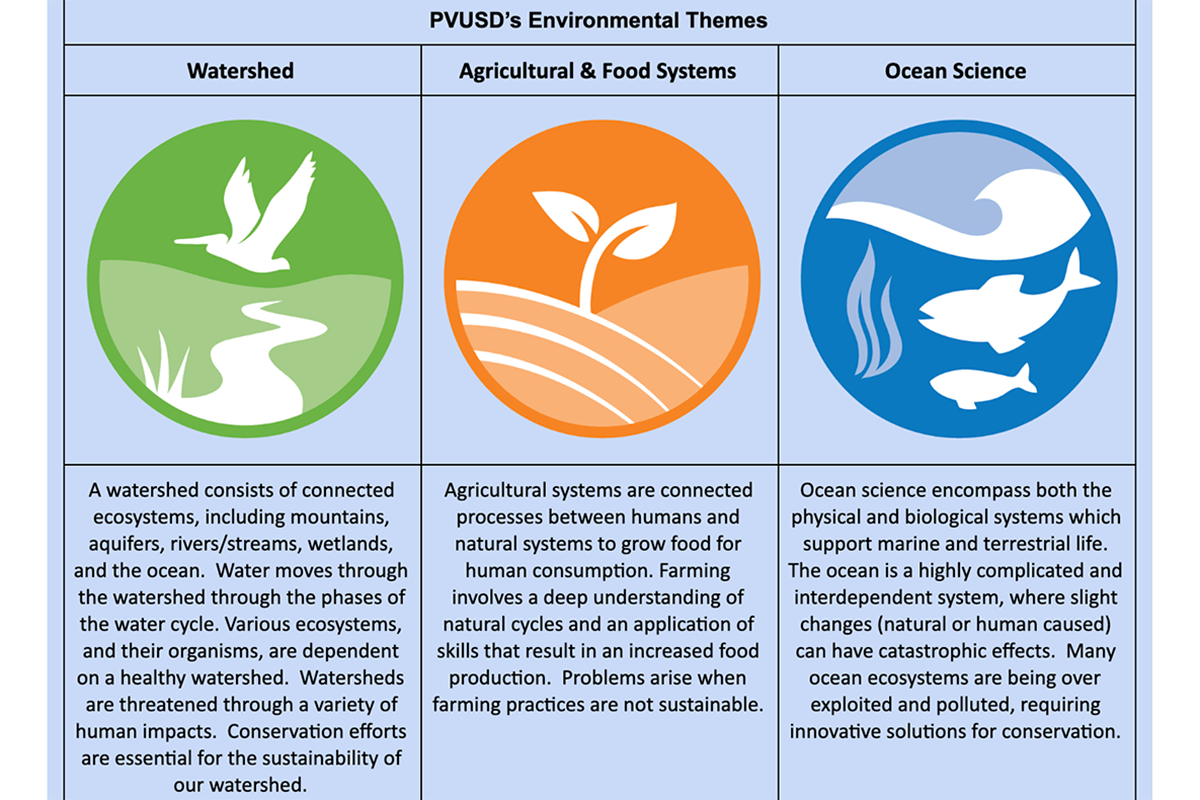

They brought with them the Lawrence Hall of Science and the Hall’s BaySci program. Their combined expertise included NGSS resources, transition mapping tools, and collaborative processes that encouraged the district to identify innovative educational goals to meet new state standards. Additionally, they worked to expand on the initial work Amity had done, built upon her mapping and landscape analysis, and contributed structural support to the work already underway, assisting in identifying placed-based themes that support opportunities for inclusive, equitable, and culturally relevant learning for PVUSD students.

The ChangeScale–BaySci work was focused on responsiveness to SCCoE’s and PVUSD’s high-level vision: alongside the academic success of their students, they prioritized long-term sustainability of district structures and systems, cohesive math–science models, high quality professional development for teachers, deep community partnerships, and culturally relevant place-based learning.

Every person I encountered at each level—including district leaders, program partners, community-based organizations, nonformal providers, and teachers—shared a common refrain without exception: the most critical element for achieving sustainable success is working together in partnership with others.

There is no deterring the students in their lakeside endeavors, and the excitement upon spotting a hoped-for bird has become inseparable from the logical responsibility they feel to remove the unnatural misplaced human debris from their new friends’ home. To her credit, Julie doesn’t even try; she rolls with the changes of timing and plans like a blackbelt in some form of martial arts that all educators who are deeply committed to their students seem to embody. When the students’ additional activities and exuberance threatens to cut into a predetermined, future-oriented recess, she lets them know then lets it go. Regrouped and reorganized, we prepare to head back to Amesti. The wagons that had previously transported clipboards and juice boxes are now laden with full black bags.

As state-level leadership in California transitioned, so did the Environmental Literacy Task Force. In 2018 CAELI evolved from that work, building upon the foundation that had been laid. ChangeScale, LHS, CDE, CalRecycle, the State Education and Environment Roundtable, the California Subject Matter Project, and Youth Outside among others have been instrumental, committed, longstanding partners in the work from the very beginning. CAELI works from a theory of action consisting of three main components—creating a supportive statewide context for environmental literacy, infusing environmental literacy throughout the K–12 education system, and demonstrating through pilot programs that any school district can successfully work toward districtwide environmental literacy programs to achieve academic success and equity of access to culturally relevant environment-based learning for all California students.

Several districts and county offices of education are now engaged in this work of infusing standards- and environment-based learning as a foundational component of their students’ K–12 educational experience in science, history–social science, health, and other subjects with CAELI partners. Pajaro, along with Alameda, Petaluma, Evergreen, San Francisco, Montebello, Rialto, Fontana, and Anaheim are part of this critical work.

As a result of these partnerships, teachers at every Pajaro school have participated in high quality professional development focused on culturally relevant science learning based in the local environment.

Every Pajaro student visits the Monterey Bay Aquarium, engages with other community-based providers to access expanded educational opportunities, and regularly participates in outdoor learning. Like Jay’s actions alongside Green Valley Road—and Rita, Amity, and Rob’s activities in Pajaro—CAELI’s work with PVUSD caught the attention of those nearby. This has led to a separately-funded, countywide effort by all ten districts in Santa Cruz to implement NGSS with special attention to environmental literacy and cultural relevance. CAELI supports these efforts by bringing additional resources to districts, affirming models of partnership that empower students, teachers, administrators, and communities to set and attain goals, while honoring each other and all the places we call home.

I look at Jay, who is taking in an improved stretch of Green Valley Road with much satisfaction as the class walks back to Amesti; I can’t help but see Rob and all of the good work in Pajaro. How many visionaries might we be losing, falling through the cracks of a system we can instead shore up by working together? How many future solutionaries are being lost, locked in cages in prisons and internment camps on this land America has claimed as its own, but has failed to care for? How do we avoid becoming numb to the garbage, remaining ignorant to the learning available through community, failing to initiate the actions that restore balance? How do we preserve hope so that we do not walk, unaware, right past the gifts and opportunities hiding in plain sight?

The students, once again, have the answer: our charge is to hear them, and join in the work of enacting the solutions. Please take a moment and listen to their voices.