Outdoor learning has taken on many meanings over the last hundred years, especially since the global pandemic. It can be seen as learning about local ecosystems, survival skills, agriculture, or simply taking the lesson that would otherwise be taught within the four walls of the classroom and bringing it outside to a circle of stumps. The benefits of outdoor learning are numerous. What remains difficult is the arduous task of replicating what is happening inside the classroom under the natural elements and the students’ tendency to view “outside” as play time. We cannot simply move the classroom; the teaching method also needs to change. Educators need to approach outdoor learning not just with outside-of-the-box thinking but perhaps as if there is no box at all.

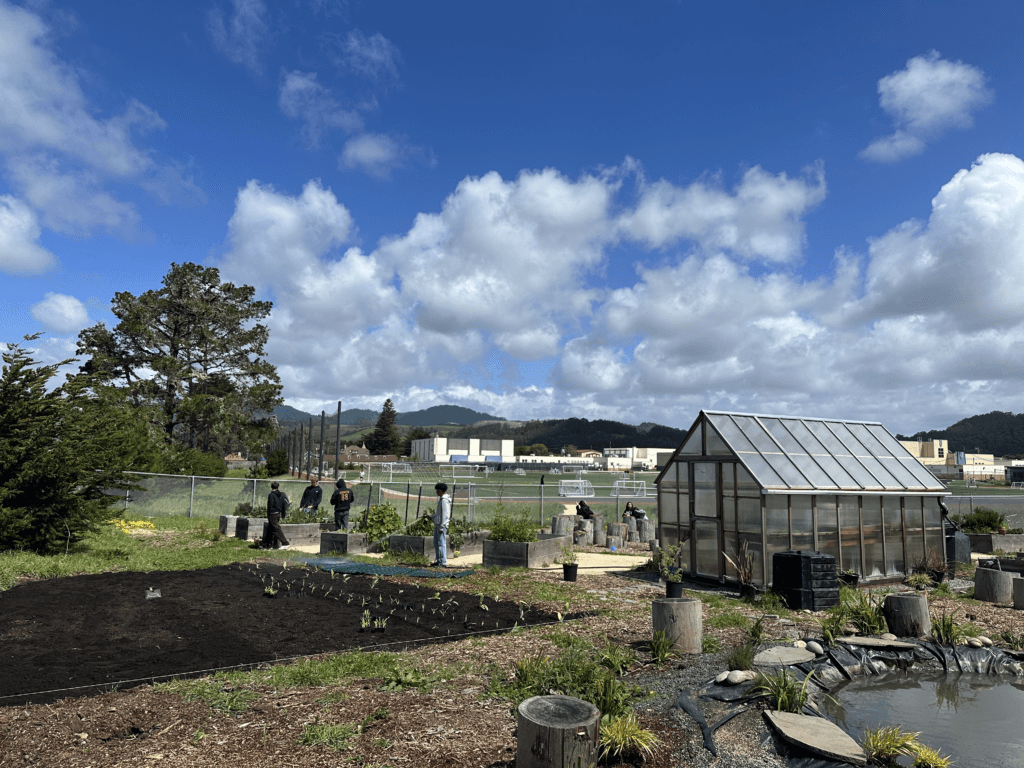

Four years ago I started in Half Moon Bay at Cunha Intermediate School, a public middle school, after seven years at a private elementary school. There was a space for teaching one elective in my schedule, and I was given a choice. I immediately chose a gardening and composting class. We live in a coastal agricultural town where many students have parents who are farm workers and who own farms and ranches. Our local high school established an agricultural science pathway in 1945 and is the only high school in our county that offers this program. All of the local elementary schools have a gardening program through The HEAL Project. The middle school was missing this component that would create continuity within our district. This is where I decided to build an outdoor classroom, by way of a farm.

When deciding to begin a project of this scale, there needs to be an understanding of the long-term commitment that it entails, and the first thing you need to do is ask yourself why. Why is outdoor learning important, and why do I, personally, want to offer this to my students and future students? When we know our why, we can build upon this foundation and stay the course when times get tough. Outdoor learning allows students an opportunity to connect with the land and with their community so that they learn to appreciate it and in turn want to care for it as stewards. I wanted to offer this to my students because I too wanted to be outside, I am not afraid to teach unconventionally, and I desperately wanted to bring back the simplicity of learning and put education into the hands of the students. My model for outdoor learning was based on student choice, autonomy, and learn-by-doing. The objectives were simple: helping students find their place in the natural world, creating a sense of stewardship with the land, and promoting advocacy.

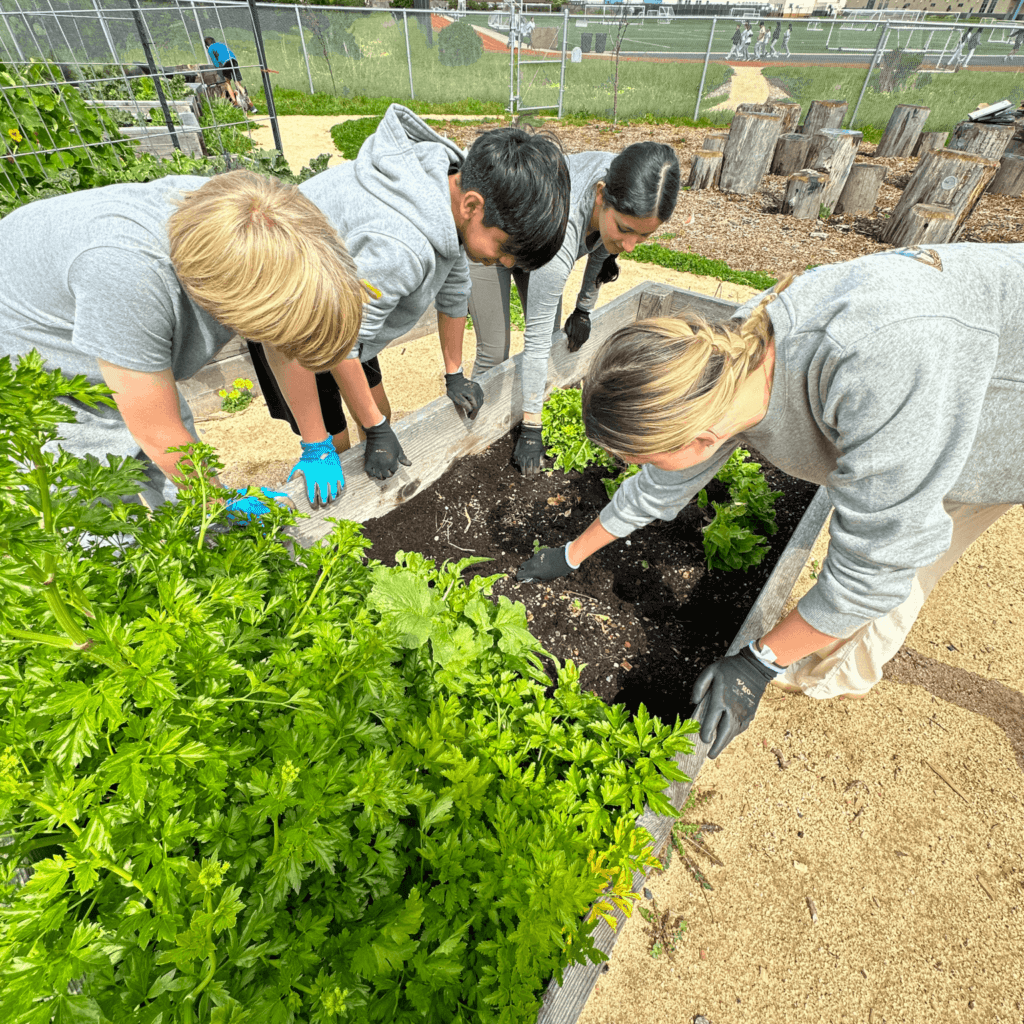

Everything grown on the Little Cunha Farm is either used in the kitchen, taken home with students, shared with staff, or given to our chickens. Students are directly involved in all processes

Once the why is established and you have committed to the longevity of the project, then comes the work of building your classroom. If I were to chronicle the last three years of the building of the farm, the curriculum, and the program, I would need a publishing contract for a full-length book. Instead I will give you the top ten action items that helped me build a successful outdoor learning environment (a.k.a. The Little Cunha Farm):

- Do your research. Go out and physically talk to the people that are already building outdoor classrooms. Sit with them, listen, and see their operation. Step out of your comfort zone and just reach out. Take pictures, make notes, ask questions. This proved to be invaluable to me. One teacher in particular gave me access to all her lessons, outlined all the obstacles that will indefinitely come up, and then reminded me that this would be the students’ favorite class.

- Build a network of community partners. There are valuable resources and contacts that are offered in your county and communities that you may be unaware of. The San Mateo County Office of Sustainability helped me with composting, in-school field trips, connections to others, and resources. Our local Resource Conservation District gave me direction on what and where to plant, aided with grants, and was a helpful platform for throwing out ideas. The Environmental Literacy and Sustainability Initiative at the San Mateo County Office of Education offered professional development, an actual person to do a site walk and help create a blueprint for the space, and on-going support in grant writing.

- Get to know your maintenance staff. Problems will arise, and there will be projects you’ll want to engage in that will require labor and problem solvers that you do not want to write a grant for. If water is shut off and your plants in the greenhouse are soon to dry up, you need to know who to call.

- Learn about career technical education (CTE). CTE is a long-standing program that outlines a pathway for students after high school. While this may not seem applicable to you, what is of value is the program’s focus to see a task done over a span of years and a different approach to learning. I was part of a “green career pathway” for middle schools that offered professional development, access to grant money, field trips, materials, and resources. Our local high school CTE coordinator was instrumental in helping with grants and finding opportunities that lifted our new program up and out.

- Write grants. It takes a lot of money to build a proper outdoor learning environment. Apply for as many grants as you can, keep writing, ask for help in editing, and don’t give up.

- Get in touch with local businesses. There are people that want to help and support outdoor school programs. Let people know what you are doing and see where they can help. I have done it with our local feed store, flower shops, nurseries, and landscaping businesses.

- Try new things. Be open to new ideas. Where can your lessons lead? Some of our projects led us back inside to the kitchen, where we used food we grew and learned some history alongside.

- Learn-by-doing. Learning outdoors cannot be taught the same way an indoor class is taught. Let go of traditional ways of teaching, and give students more autonomy in their tasks. Allow them to make mistakes, and give them the space to come up with their own ideas.

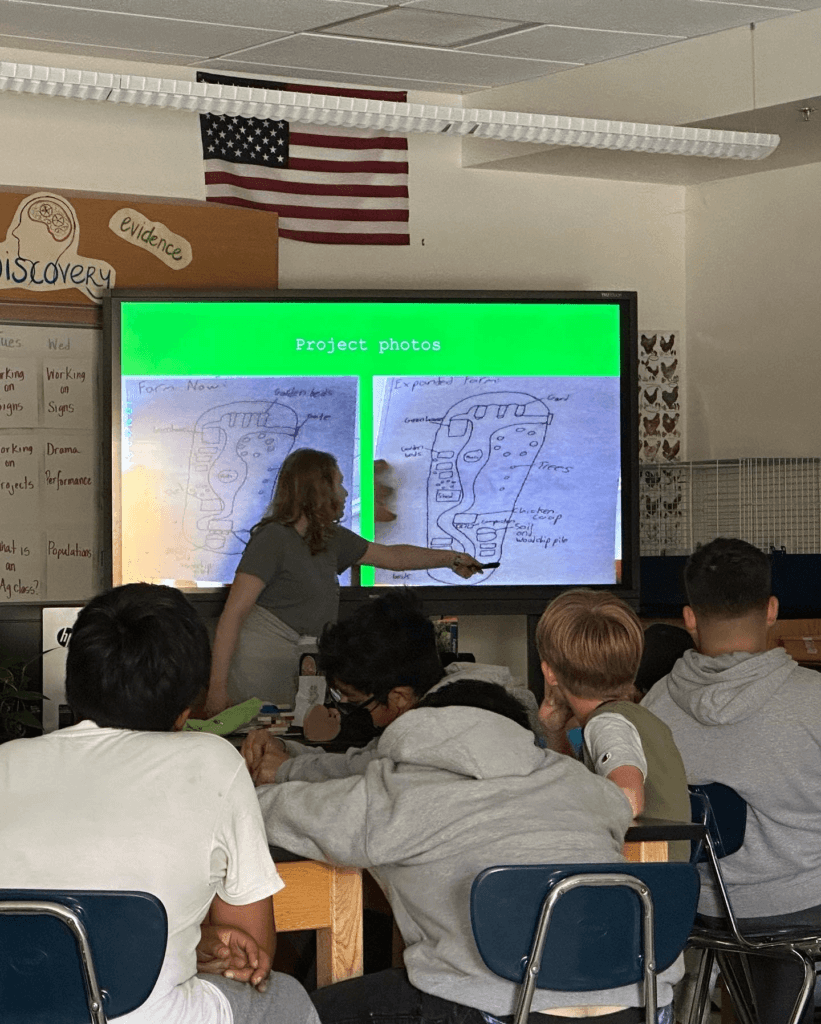

- Assign student action projects. Everything on our farm came from the ideas of students. At the end of the term, students have a project answering one question: How can we use sustainability, stewardship, and regenerative agriculture to create spaces for all students at our school to enjoy and thrive? Listen to your students’ ideas, give them space to be creative, and then find the money to make their ideas come to life.

- Assign student action projects. Everything on our farm came from the ideas of students. At the end of the term, students have a project answering one question: How can we use sustainability, stewardship, and regenerative agriculture to create spaces for all students at our school to enjoy and thrive? Listen to your students’ ideas, give them space to be creative, and then find the money to make their ideas come to life.

Our story is ongoing, ever evolving, and it comes with a lot of ups and downs. The day-to-day can feel like trekking through thick mud, but what started with a few garden beds has grown to three progressive classes (sixth, seventh, and eighth grade) involving fifty percent of our student population, a farm with an egg business, and continuity of outdoor learning in our district that was honored with the 2024 silver level Green Ribbon Award. The beauty of this program is that there are constant modifications and extensions. I chose to “go big” because I wanted to alter the culture of the learning environment to truly put students at the forefront.