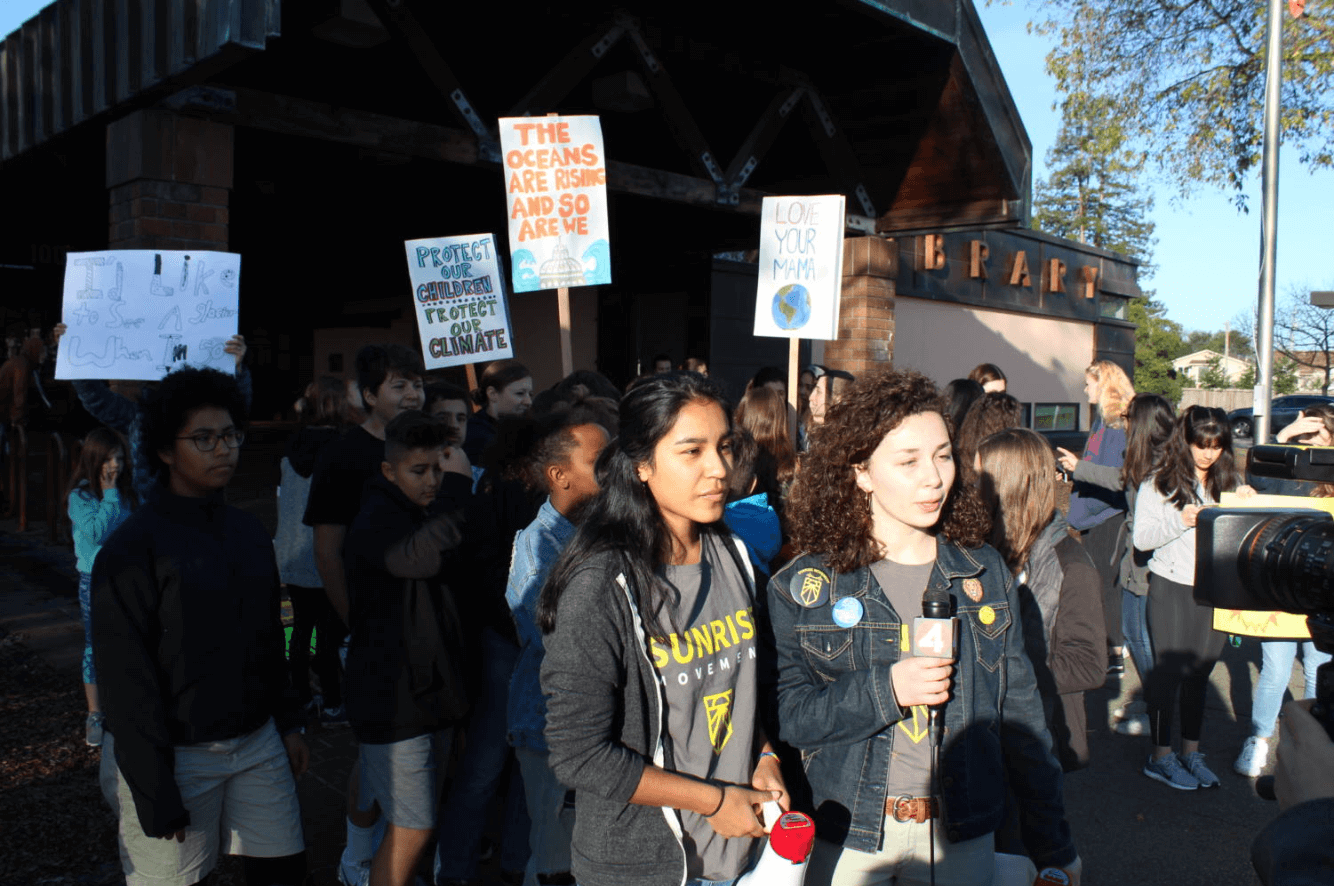

This article is part of our Youth Voices series. At Ten Strands we believe that young people have valuable perspectives and a critical role in shaping our society and our world. We recognize their power to drive dialogue and create positive change, and are committed to providing a platform which amplifies their contributions.

For the longest time, I saw climate change only as the melting of ice caps and the clearcutting of rainforests in faraway, obscure parts of the world visible only in documentaries and news reports. My parents always made sure I was aware of the issue, but I was never awake to it. After all, I lived in California where the seasons were never too hot or too cold, my house was always air conditioned, and I always had enough to eat. I cared about climate change, but I was disconnected from it. It seemed to affect me as much as starvation or malaria.

That all changed on Monday, October 9, 2017. That morning I woke up to a world on fire. I couldn’t go outside because the air was thick with toxic ash. I couldn’t see the sun because black smoke masked the sky. I couldn’t breathe without tears coming to my eyes. I couldn’t believe what was happening until I could see the glow of a fire coming over the hill I can see from my house. My home state was burning.

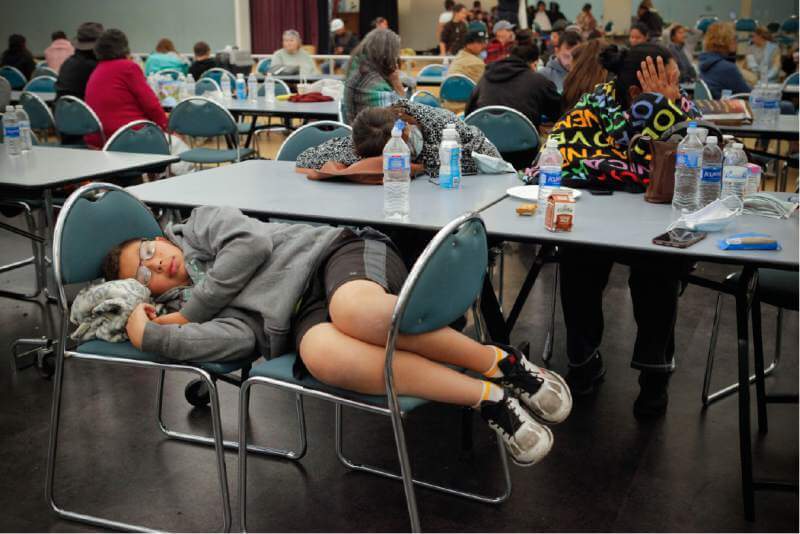

Terrified that the fire would come over the hill and our neighborhood would be the next to burn, my mother moved us to stay with friends at Dillon Beach. Surrounded by the unspoiled California coastline, suntanned surfers, and the rolling waves of the Pacific Ocean, we still couldn’t escape the reality of the fire. Smoke spilled over the blue horizon like a wound ripped open over our lives. Every day my phone buzzed with new alerts. New houses had burned, new lives were lost, further tragedies recorded. After a few days, my mother decided it was safe enough for us to go back home. As soon as we did, we entered a world I had never seen before. We could go nowhere without particulate masks, and the smoke down the street was thicker than the fog that obscures the city of San Francisco. My school was a refugee camp; the gym and classrooms were a temporary shelter for those who had lost everything in the fire. I watched my peers try to console children who had lost everything. I watched my teachers struggle to find medicine and food for the families who had escaped with nothing but the clothes on their backs. I watched my community lose so much, and then rise from the ashes together to rebuild what was lost.

The fires brought out the very best of the people in our community, but we should never have been forced to suffer as we did. The wildfires were unnatural, started by human error and fueled by decades of resource mismanagement. The ecosystems of California are built to be balanced and maintained by regular, small-scale fires. The balance is upset by mismanagement and poor land stewardship, and the fires are the price we pay for neglecting our responsibility to the land on which we live and from which we profit. After the first fires I started to research fire ecology, trying to understand if there was a reason behind all of the destruction. What I know now is that the fires that ruined so many lives could have been prevented.

The destruction caused by fires makes many people afraid, and often their first reaction is to suppress fires, including those in the wilderness, started not by people, but by natural causes. Low-intensity fires, fires that burn low to the ground and at relatively low temperatures, increase the environment’s fertility by burning away an overabundance of underbrush and transferring the burned organic matter back into the soil. These low-intensity fires are usually started by natural causes and are much easier to control. In our California ecosystem, fire acts on the environment in a similar way as grazers, like elk and deer, do. Naturally, fires burn at regular intervals in our ecosystems: this keeps vegetation from becoming overgrown and choking out other species, decreasing the biodiversity, and destroying an otherwise healthy system. Many plants in California depend on fire as much as they do on water or air. The knobcone pine needs a fire of over 350 degrees Fahrenheit to open its sealed pine cones and spread its seeds over the forest floor, devoid of competition now that the fire has burned away all the other plants.

The original land stewards, the Natives of California, knew how to use fire appropriately long before Europeans came to America. These Native Americans often started brush fires in strategic places to flush out prey or even to clear space for desirable plants to grow. Early settlers describe California as a beautiful, diverse, and purely wild place. It’s entirely possible that this was no accident, but the result of thousands of years of land stewardship and careful resource management.

We’ve lost the practices that were so artfully employed to cultivate a diverse and resource-rich biosphere in California. We suppress fires, even in the wild, because we build our homes in their path; however, to suppress fires doesn’t mean we prevent them, it merely means we are ensuring a more destructive result later on. The more often we suppress fires, the more biomass is allowed to accumulate, and the stronger and higher the intensity of fires will be in the future. Eventually there will be another fire, and because we didn’t allow smaller, lower intensity fires to burn as they were supposed to naturally, the result will be an even more destructive and higher-burning fire.

Instead of learning to coexist with the natural forces that surround us, we fear them. The “Smokey the Bear” mindset teaches that fire is an enemy to be conquered. We think of ourselves as separate from the wild, when in fact we are just as animal as the elk, the mountain lion, the hummingbird, and the coyote and therefore just as dependent on our environment, no matter how much we try to change that. Most of today’s conservationists, biologists, and outdoor specialists believe that the best way to conserve nature is to preserve it. We take a hands-off approach to protecting the wild, believing that our best influence on the outdoors is no influence at all. I would argue that this approach fails to take into account that we have already changed the world around us and we cannot separate ourselves from the natural world. Preservation is not the answer to saving our planet and halting climate change. Instead, we must become land stewards, and care for the earth as much as we would our own homes.

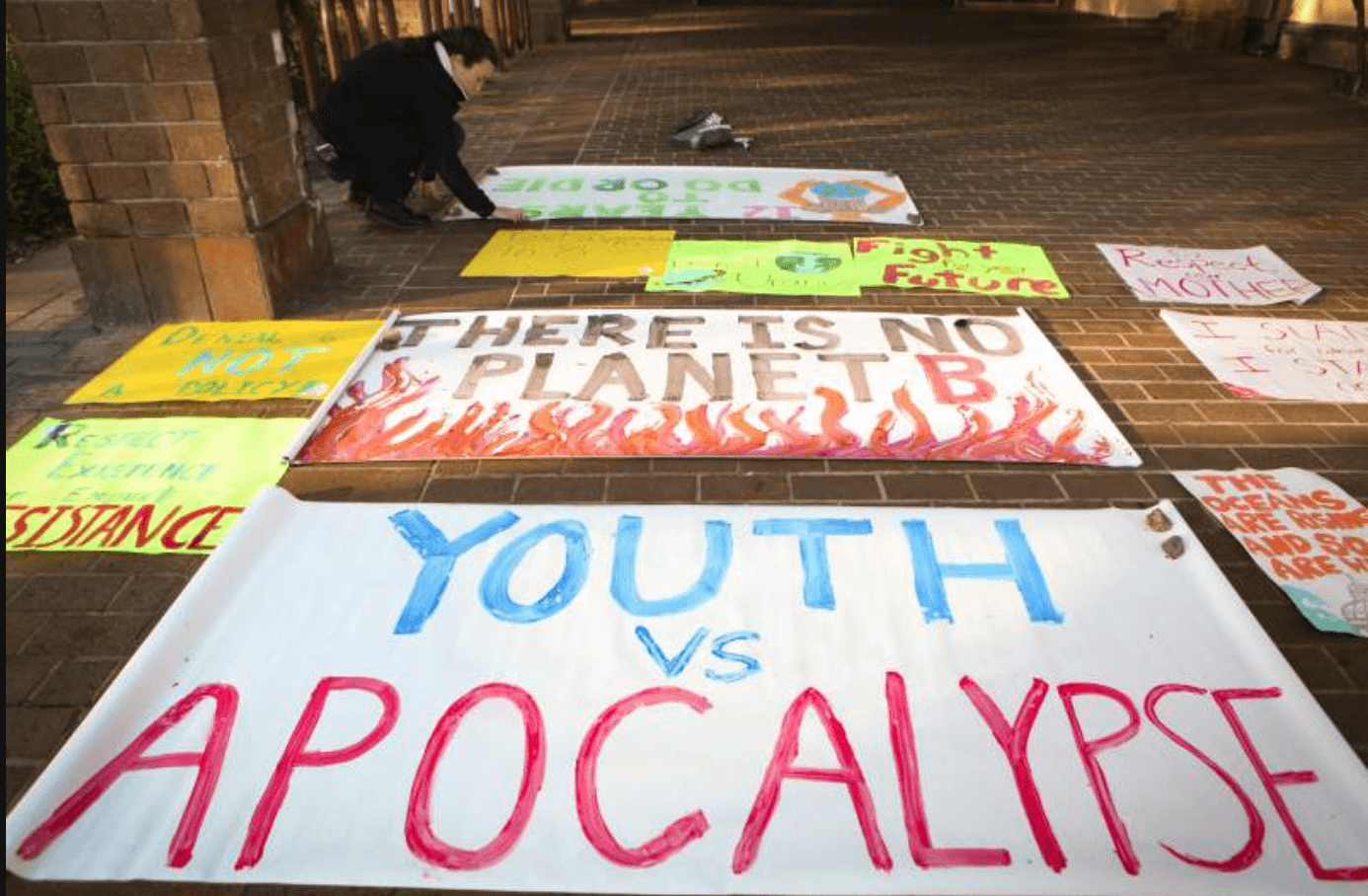

I have stood on the front lines of climate change. I believe that the only way to keep California from burning, to keep Antarctica from melting, to keep the Amazon from shrinking, to keep the Middle East from being parched dry from any water is to accept that we are not separate from our world, we are a part of it. With this knowledge, we may be able to cultivate not only a thriving ecosystem, but a better world.

5 Responses

We stand proudly with you

Yes, Lucia, I agree we must “accept that we are not separate from our world, we are a part of it.” Wonderful reporting!

Thank you!

Awesome writing. So proud of you!

Lucia, I hope I speak for all of the octogenerians in your life and in mine in saying we are so proud of what you and your generation are doing to save our planet. Your Grandpa Tom was a good friend and fraternity brother of mine. I know he would be as proud of the work you and your contemporaries are doing as I am. Keep it up. Wish that we had done 1/4 of what you are doing.

Hear hear Lucia! Splendid job of succinctly describing the local effects of our global existential crisis. We support you in your efforts to bring light into the darkness of human unconsciousness.