Are we experiencing a “Goldilocks Moment” for Ten Strands’ efforts to be successful in environmental education? In The Big History Project by David Christian, he describes the reason the earth began supporting life to be that conditions were just right: not too hot and not too cold, but just right. I think the same can be said for why Ten Strands’ efforts in environmental education are taking off.

Let’s look into those conditions, and assess if the Goldilocks Moment has truly arrived. To start us off, here is a list of some current conditions:

- California now has a Blueprint for Environmental Literacy, as do 20+ other states.

- The California Department of Education invited Ten Strands into the process of revising the Science Framework to ensure that the Environmental Principles and Concepts are appropriately interspersed throughout the Framework in accordance with California law.

- The California-adopted Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) make environmental connections throughout.

- At the U.S. Conference of Mayors last month, mayors across the country in cities including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, Fremont, Boston, Phoenix, and Seattle passed a resolution calling for the “swift implementation” of climate education in high schools nationwide.

- The California Parent Teacher Association (PTA) adopted a resolution in May stating that students and parents need to become environmentally literate around climate change’s impact on children’s health.

- Pope Francis published his encyclical “to all people of good will” in June, imploring all to interpret “dominion over earth” to mean that we must take later generations into account as we consume resources. We must not be so profligate in our consumption of earth’s resources that we leave future generations a decimated world.

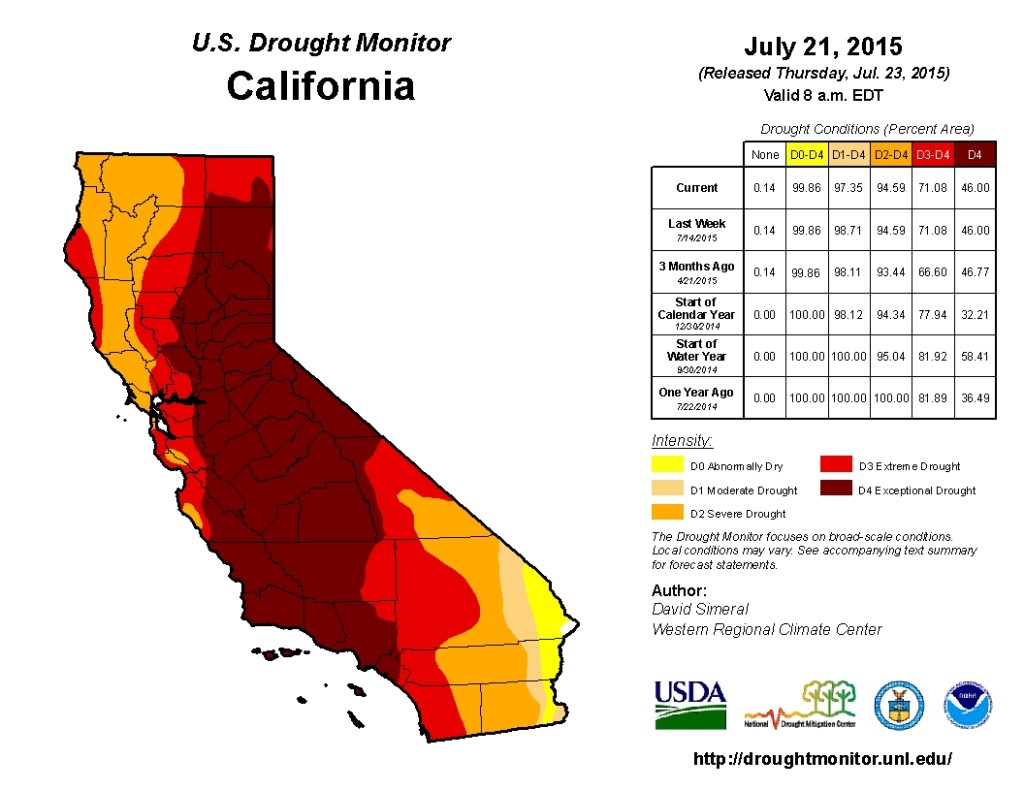

Locally, add the California drought and you get the Goldilocks Moment that just might be sufficient to catalyze interest in environmental literacy for everyone.

As I consider our readers “people of good will”, I’d like to explore what the Pope’s encyclical suggests about the importance of education to achieve environmental literacy.

Around the world, the encyclical is raising hopes that governments will take bold climate action. Bonn-based Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, said, “Pope Francis’ encyclical underscores the moral imperative for urgent action on climate change. This clarion call should guide the world towards a strong and durable universal climate agreement.”

In Washington, World Bank President Jim Yong Kim, said, “We must now seize this narrow window of opportunity and embark on ambitious actions.”

Kumi Naidoo, Executive Director of Greenpeace, said that the Pope’s encyclical “brings the world a step closer to that tipping point where we abandon fossil fuels and fully embrace clean renewable energy.”

There are three things Pope Francis said that give me the most hope.

The first is that he left no doubt about who’s to blame—he totally supports the scientific findings that climate change is man-made, highlighting that compelling conclusions of credible scientific studies “indicate that most global warming in recent decades is due to the great concentration of greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen oxides and others) released mainly as a result of human activity.” (Emphasis added)

The second is how he reinterprets the idea of human dominion over earth. He says that each generation must keep later generations in mind as it makes decisions about consumption, as “nowadays we must forcefully reject the notion that our being created in God’s image and given dominion over the earth justifies absolute domination over other creatures… Each community can take from the bounty of the earth whatever it needs for subsistence, but it also has the duty to protect the earth and to ensure its fruitfulness for coming generations… Clearly, the Bible has no place for a tyrannical anthropocentrism unconcerned for other creatures.” (Emphasis added)

The third is his caution about thinking that technology can simply fix everything that is wrong with the environment. He acknowledges that technology is good at solving short-term problems, but cautions that complete faith in technological solutions is based, “on the lie that there is an infinite supply of the earth’s goods, and this leads to the planet being squeezed dry beyond every limit. It is the false notion that an infinite quantity of energy and resources are available, that it is possible to renew them quickly, and that the negative effects of the exploitation of the natural order can be easily absorbed.”

He goes on to say, “Technology can solve one problem at a time, but it can’t solve for the larger confluence of the interconnectedness to the whole of nature, environment and the poor…This very fact makes it hard to find adequate ways of solving the more complex problems of today’s world, particularly those regarding the environment and the poor; these problems cannot be dealt with from a single perspective or from a single set of interests.”

He absolutely crushes it here with his statement that technological solutions only hit one problem at a time. Comprehensive solutions must be delivered in context with social mores, using education and spirituality to provide context for the whole:

“Ecological culture cannot be reduced to a series of urgent and partial responses to the immediate problems of pollution, environmental decay and the depletion of natural resources. There needs to be a distinctive way of looking at things, a way of thinking, policies, an educational programme…To seek only a technical remedy to each environmental problem which comes up is to separate what is in reality interconnected and to mask the true and deepest problems of the global system.”

He acknowledges that just passing laws is insufficient to create behavior change: it is the power of education that creates conditions for reforming the way humans interact with the environment.

“If the laws are to bring about significant, long-lasting effects, the majority of the members of society must be adequately motivated to accept them, and personally transformed to respond… Education in environmental responsibility can encourage ways of acting which directly and significantly affect the world around us, such as avoiding the use of plastic and paper, reducing water consumption, separating refuse, cooking only what can reasonably be consumed, showing care for other living beings, using public transport or car-pooling, planting trees, turning off unnecessary lights, or any number of other practices.”

He continues in this line of reasoning: “Ecological education can take place in a variety of settings: at school, in families, in the media, in catechesis and elsewhere. Good education plants seeds when we are young, and these continue to bear fruit throughout life. Our efforts at education will be inadequate and ineffectual unless we strive to promote a new way of thinking about human beings, life, society and our relationship with nature. Otherwise, the paradigm of consumerism will continue to advance, with the help of the media and the highly effective workings of the market. “

In summary, the Pope’s encyclical gives me hope that the Goldilocks Moment for real education about the environment may be occurring. We are achieving traction at integrating environment-based themes into core subjects and are giving voice to a perspective that has hitherto been relegated to special courses called “environmental studies” or “environmental science”. Don’t get me wrong—these subjects will continue to be important and critical to delve more deeply for those interested—but all students can incorporate a more sophisticated knowing about humanity’s deep connection to natural systems within core subject areas. Our public schools are best situated for that intellectual and experiential knowledge to grow, especially since teachers overwhelmingly want to teach material that ties to the environment. Our dependency on nature down through the ages has not changed, and thus it will be as far as my eye can see into the future.

The guidance provided by our country’s mayors, our Parent Teacher Associations, leaders of the World Bank and the UN, and even the Pope gives me hope, as Julia Louis Dreyfus says about Ten Strands work, “Hope that the next generation will rally to support the decisions to make the world healthier and more sustainable for everybody.”