Public Education System Historical Context

The K–12 public school system is where students are given an opportunity to gain knowledge and skills for a successful life. It’s important for children from all communities to receive a high-quality education to thrive as individuals and become contributing members of society.

Beginning in the mid-1900s, in the US, children from all social classes could theoretically get a free formal education under the compulsory education laws, although overwhelmingly, schools were attended by white male students. Schools taught national unity and “American” values to support the burgeoning industrial economy requiring laborers who could read, write, and do arithmetic. Education’s goal was preparation for success in a life steeped in Manifest Destiny, individualism, competition, and survival of the fittest. Equitable distribution of education across social classes and the economic strata was not a priority. Many factors—including slavery, discrimination, and discriminatory laws against Black, Indigenous, and people of color as well as individual towns having to create their own educational system with vastly differing financial capacities—led to the inequitably funded education system operating across the US today with enormous inequality in educational opportunities.

Public schools, working in partnership with parents, caregivers, families, businesses, and community-based organizations, can become hubs of opportunities for children from all backgrounds to learn together and from each other. Huge disparities in wealth and educational opportunities still plague educational systems.

In 2021, public education is still the largest social institution responsible for preparing students for a successful life. Along with all the existing challenges, a new one has emerged—climate change.

Only recently emerging in the public’s consciousness is the existential threat of climate change to all of humanity. Human decisions have not only triggered climate change, but massively exacerbated it. Being prepared for success in the 21st century must now include learning about how complex decision-making, individually and collectively, will either help or hinder progress against the global menace of climate change and environmental injustice disproportionately experienced by systemically under-resourced communities and people of color.

As our nation moved from an agrarian to an industrial society, education had to change. It now needs to change again, deep into the information age, as we move toward an age threatened by climate change, tensions around reckoning with racism, and inequitable funding of schools worsening as income disparities grow. The acceleration of climate change, and other societal issues, is giving the K–12 education system an opportunity to again rethink how to implement its purpose of preparing students to be successful in life as well as contributors to a better world.

The need has become paramount for humanity to recognize how the destinies of eight billion people, and growing, are interconnected not only to their communities, but to the health of planet Earth’s natural functions. Astronaut William Anders’s 1968 photo of the earth rising above the moon’s horizon provided evidence of Earth as a closed system with finite resources, not infinite, relying much more on cooperation than competition for its health.

This photo galvanized the position of Earth as a closed system with finite resources working with cooperative functions. Photo credit: William Anders.

This photo galvanized the position of Earth as a closed system with finite resources working with cooperative functions. Photo credit: William Anders.

Education for All Students to Become Contributing Members of Society

I founded Ten Strands with the belief in education’s ability to embrace the task of giving all students an opportunity to learn how decisions they make throughout their lives can alleviate and even reverse climate change and the environmental injustices associated with it that disproportionately affect the communities that are the most impacted.

Teaching K–12 students about the interdependence of humans and the environment engages them with ideas they already are keenly interested in. In my ten years teaching high school environmental science and senior civics, I learned how deeply our students want to understand environmental topics relevant to their lives. I also learned how to use our students’ own environment as an engagement strategy to boost overall learning.

One day, I brought a Twinkie into the classroom and started a discussion about the inequities around fresh food availability in many Bay Area neighborhoods. For weeks, the seniors were engaged in conversations about food deserts, unhealthy diets, poor access to clean water, asthma associated with power plant smokestacks, and so many other topics. Civics suddenly became real to them as they saw the potential for finding solutions to the environmental issues plaguing their neighborhoods by getting involved with community wellness efforts and civic engagement. The students from the most impacted neighborhoods brought their own lived experiences into the classroom and enriched the conversation far more than any readings or videos could have done.

Using the environment as a context for learning is both a means and an end. Learning about climate change and environmental injustice issues weaves a cohesive tapestry among all the core subjects and makes them more interesting, relevant, and engaging. Students get an opportunity to learn critical thinking skills in real-time problem-solving settings, and to work in cooperation with each other preparing them for an age when focusing on climate change solutions will be a societal imperative.

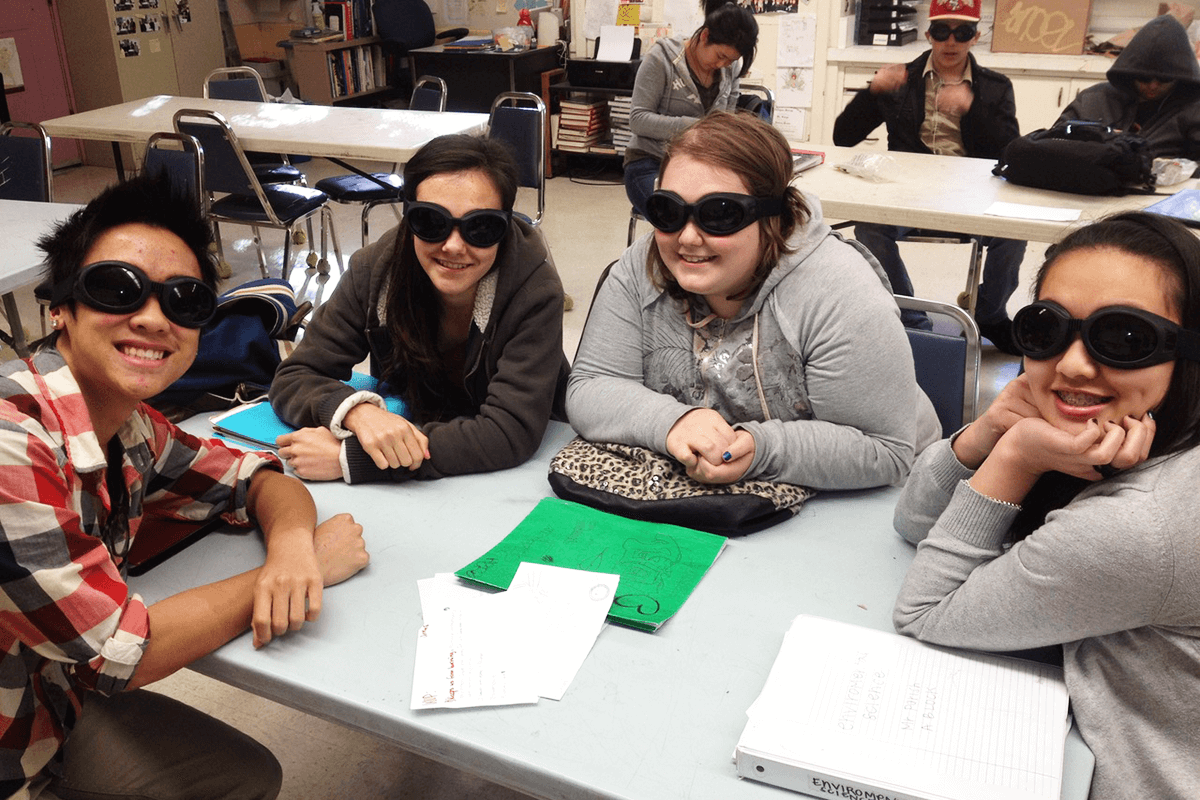

Mr. Parish’s Gateway High School students preparing for a solar project.

Mr. Parish’s Gateway High School students preparing for a solar project.

Making environmental and climate literacy a priority in schools is Ten Strands’ objective: to move toward current ideas about learning; toward understanding how our well-being depends upon the collective action of eight billion individuals; and toward embracing the world environment as a closed and finite system in the throes of a human-caused extinction event already in motion. It must be reversed.

No other institution is up to the task. It has to be public education—on a large and sustainable scale. Without education, we won’t see how the environmental catastrophes we read about almost daily are connected to human activities altering the environment. We cannot afford the consequences of mass environmental ill-literacy!

Student activists like Greta Thunberg and Isha Clarke, the climate protests, and the nonprofits fighting fossil fuel companies are the emergency flares illuminating climate change catastrophes and environmental injustices. These efforts are absolutely critical, but they don’t provide the sustained daily learning needed to generate the massive education to create the societal commitment required for a wholesale shift in civic consciousness and habits. While we can see local flooding, smell forests burning, feel temperatures rising, and witness social and environmental injustices, we can’t know the deeper systemic causes until we learn about them.

Students don’t come into the classroom with a blank slate. They bring with them their lived experiences as mentioned above. Having voices in the classroom of people who are actually living with environmental injustices makes the learning visceral and vivid and real. What an asset in a school setting to have voices providing a diverse array of perspectives.

Students come to school influenced not only by their lived experiences, but with the information they stream on their devices. Much of it includes a lot of counter-education, pushing consumption and competitive individualism with devastating impacts on the environment.

California Lays the Foundation for Environmental Literacy

In 2003, then state Senator Fran Pavley brought to the California legislature the idea of using public school education to foster a deep understanding of human to nature interdependence. She had been a classroom teacher for 30 years. She knew the widespread reach of the public school system and the inherent interest children have in understanding, and wanting to care for, their own environments.

Her legislation launched a decades-long educational effort, more robust today than ever. It began with education experts developing Environmental Principles and Concepts to be taught in history-social science and science, producing a literacy, spiraling upward in complexity, about human interdependence with the environment, as a student moves through the K–12 system. In grades K–5, the effort is toward generating awe, curiosity, love, and an understanding of how everyone is not separate from nature, but a beautiful part of it and dependent on it. Students learn the complexities of where food and other goods and services come from, how goods are transported, the natural cycles, and other topics.

In grades K–5, the effort is toward generating awe, curiosity, love, and an understanding of how everyone is not separate from nature, but a beautiful part of it and dependent on it. Students learn the complexities of where food and other goods and services come from, how goods are transported, the natural cycles, and other topics.

In grades 6–8, students learn the ways in which humans are inextricably dependent on nature for the goods and services supporting life like photosynthesis, the water cycle, industrialization, urbanization, and my favorite, decomposition. By the way, a 2018 study estimated the value of those services, which form the basis of all economic activity, globally, at $125 trillion annually.

In grades 9–12, students assess data and evidence to evaluate the damage caused by human activities and consider the pros and cons of solutions such as using renewables and nuclear energy rather than fossil fuels. Ultimately, high school seniors should be well equipped to viscerally and intellectually understand how humans are part of and not separate from nature to the point where sacrificing the environment for short-term human gain makes about as much sense as giving up an arm or a lung. Going into higher education, career technical education, or the job market, students will already speak the language gaining currency worldwide embodied in environmental literacy, including climate change and environmental justice. Environmental illiteracy leads to environmental injustice. Environmental literacy leads to environmental justice.

Strands for Advancing Equitable Environmental Literacy

Schools are investments in our children’s well-being. Schools also improve society’s collective well-being by graduating skillful individuals who have knowledge, attitudes, and values emphasizing how each individual contributes and makes choices affecting their communities and the world. Teaching the science, history-social science, and economics of the environment, and using language, the arts, technology, math, and experiential learning will provide skills and knowledge to improve students’ chances of personal success while improving society overall.

The public education system is our best bet to instill curiosity, wonder, knowledge of shared problems and solutions, and to foster a stewardship ethic. All students can learn how to read the signs of humanity’s toll on the health of the planet and their communities. Peripheral programs, environmental education camps, and one-off field trips are crucial in a child’s education, but alone they are not enough to fully prepare students. Environmental and climate literacy must be an integral part of every child’s formal, standards-based education, woven into the fabric of teaching core subjects, examining evidence, data, and history to deeply understand the interdependence between humans and nature.

Ten Strands belongs to a community advancing environmental literacy as a top priority of a public-school education, rather than a nice addition if teachers have time. Together, we need to reach those who are skeptical about the power of education to support a sustainable future and reverse the existential threat of climate chaos. Advancing our work means spreading the word, enlisting new partners, and of course accessing more resources. We all need to support the teaching of environmental literacy, justice, and climate change—in all 10,000 schools in California—and beyond!

4 Responses

Will,

Thank you for the article and founding Ten Strands. I’m curious how your programs counter all the misinformation spread by those who not only deny climate change but spend $$$$ to disseminate misinformation to protect the fossil fuel and others, such as Big Ag who block all progressive policies to alleviate the problem.

Will,

Thank you for writing this article and your work integrating environmental literacy in K-12 schools. I am currently pursuing my Earth Science teaching degree and my goal is to establish more env. literacy in NYS, and am particularly interested in the role of legislation. Would love to ask you a few questions. Would you be able to contact me via the email address that I left?

Keep up this amazing work! I enjoyed reading it

Great work, but unfortunately you have been hijacked by the “social justice” campaign. Can we not have a environmental conservation and preservation program free from Critical Theory?! Answer: we can and we should.