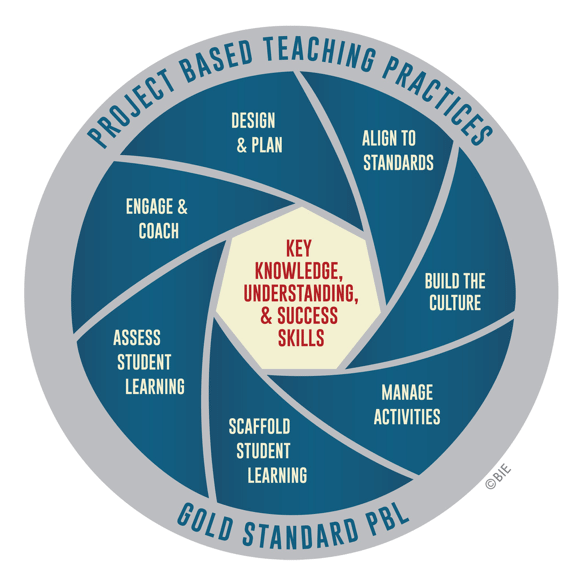

If a teacher decides to adopt a project based learning (PBL) approach, even the Gold Standard Project Based Learning unit, the most comprehensive tier of PBL strategies, starts with a simple question: What’s the content that teachers will use to foster a successful classroom?

There is no shortage of sources from which to choose: individual state frameworks and standards, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for English Language Arts and Mathematics, the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), and district-adopted curricula with ancillary online and analog components.

Harvesting the right content is just one step toward implementing a project based learning-oriented classroom. How can we as teachers best design PBL experiences that effectively integrate content standards, activities, and textbooks?

I’ve learned that designing a unit through an environmental literacy lens can effectively integrate these components, as well as closely connect students to the communities in which they live.

According to California’s Blueprint for Environmental Literacy, an environmentally literate person “has the capacity to act individually and with others to support ecologically sound, economically prosperous, and equitable communities for present and future generations.” The goal for educators working with students is “developing the knowledge, skills, and understanding of environmental principles to analyze environmental issues and make informed decisions.”

This concept was launched with the passage of California Assembly Bill 1548 (Pavley) which established the Education and the Environment Initiative (EEI) Curriculum. Following that, more than 100 scientists and experts created the Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs), which align with modern educational standards and integrate an environmentally literate focus into curricula for various subjects. These five principles and fifteen concepts will now be included in all future K–8 science and history–social science instructional materials adopted throughout California.

How can the EP&Cs coalesce project based learning content?

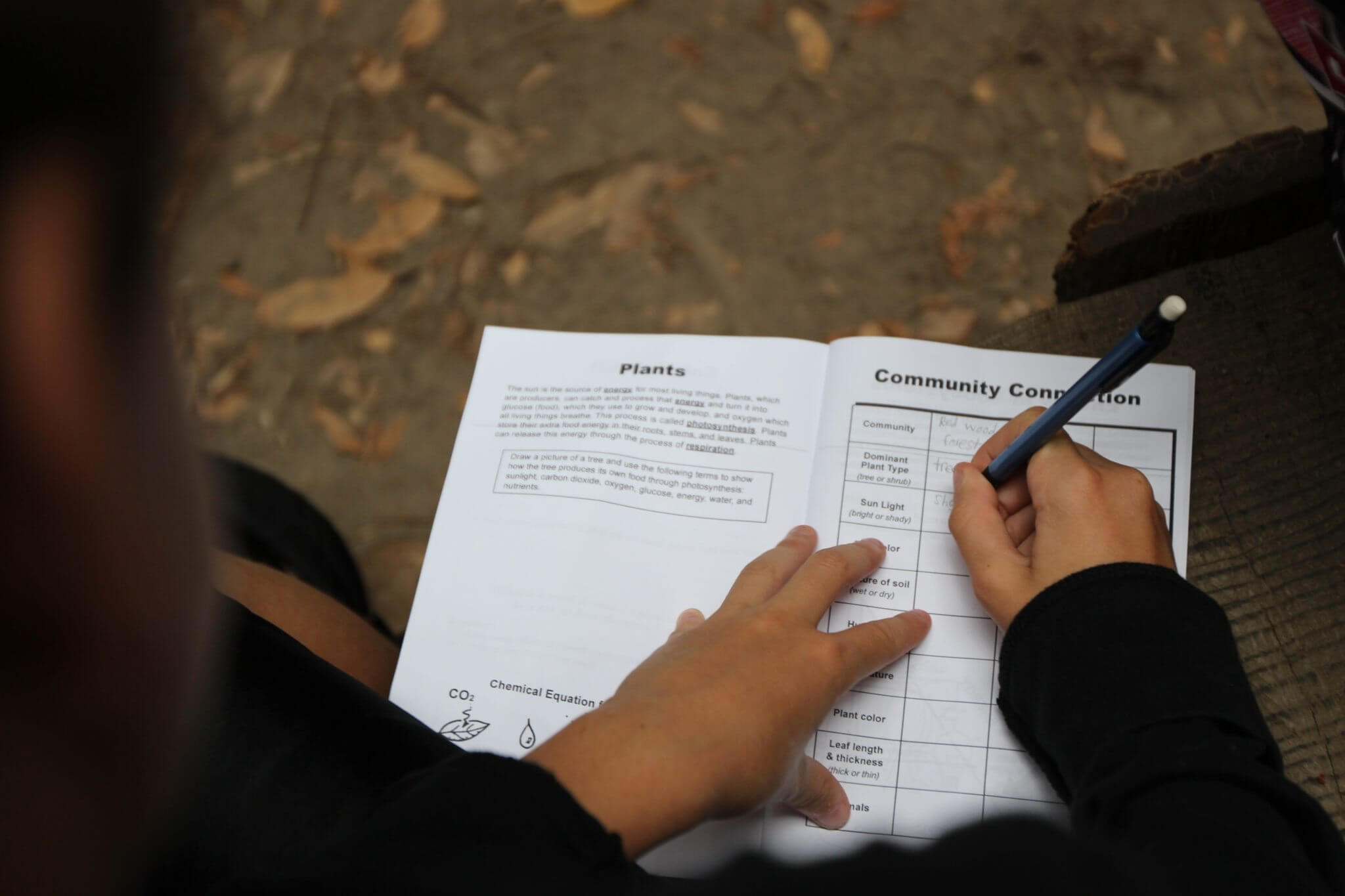

Here’s an example: When my 6th graders study the water cycle, as called for in NGSS standard MS-ESS2-4, we do more than simply “Develop a model to describe the cycling of water through Earth’s systems driven by energy from the sun and the force of gravity.”

We drill down into the topic with help from the EP&Cs while simultaneously integrating reading, writing, math, and civic education with speaking and listening, and even visual and performing arts standards.

When a previous class studied the water cycle using the EEI Curriculum alongside our textbook and a Newsela text set, they learned that one source of groundwater pollution came from improperly disposed of batteries. Less than 1% are properly recycled due to a lack of education on the part of consumers, and a lack of revenue on the part of local integrated waste departments. As students dug deeper, they uncovered the concept of extended producer responsibility (EPR), which holds manufacturers of certain products financially and legally responsible for their planned disposal. Students identified one solution to this problem was lobbying our state legislature to enact EPR legislation regarding battery manufacturers.

In an example of how the EP&Cs can be used as the backbone of a civics-oriented unit, Environmental Principle II focuses on how “ecosystems are influenced by their relationships with human societies,” something my students witnessed in their inquiry into the causes of groundwater pollution. The concept of EPR connected students’ findings to Environmental Principle II, Concept D which explores how government policies affect the “viability of natural systems.”

Students went beyond the NGSS and opted to lobby our city to install battery recycling bins in elementary schools throughout our district. The proposal was not accepted due to safety concerns, but what resulted was a multi-year collaboration with our city’s integrated waste department. We now produce instructional films on the proper disposal of trash, recyclables, green waste, and most recently organic waste. You can see my students’ work on our city’s video library website. We also created a documentary about the battery disposal project showcased on our YouTube Channel.

This project integrated a variety of standards, but it was the big ideas expressed in the EP&Cs that served as the canvas for the learning experience.

Writing and refining driving questions in a project based learning unit are essential to help students stay focused on what a project is all about. A teacher also needs a set of optics to help organize the various standards and 21st century skills to be taught.

Not sure how writing and creative connections can anchor an environment-based unit using PBL techniques? This year, I’ve turned to Principle IV, which focuses on how “the exchange of matter between natural systems and human societies” affects the health of ecosystems, and Principle V, which looks at how the decisions we make regarding resource use involve a “wide range of considerations and decision-making processes.”

The driving question for this unit: How can we as student filmmakers educate businesses about organic waste and its impact on climate change?

Students are informing businesses in our city about mandatory organic recycling programs, resulting from the passage of California Assembly Bill 1826. They’ve researched and read about various types of organic waste. They’ve learned that, as organics break down, they generate greenhouse gases that cause climate change. Students have scripted a series of 7 films and are now shooting video, or finding footage allowed for use under Creative Commons Licensing or in the public domain.

The Environmental Principles and Concepts, developed in my home state of California, have helped me look past standards as the foundation for designing units of project based learning. I no longer focus solely on the “what” of teaching. I now seek to explore the interconnections between content, students, our environment, and our role in it.

The recent appointees to head the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Departments of the Interior and Energy, have led many to question the direction of these institutes’ priorities regarding federally-mandated protections of the environment. This uncertainty signals to me that our roles as teachers requires more than simply teaching content to students. It’s preparing them to be critical thinkers, citizen scientists, and advocates for problems that may not even exist yet—and to do that will take an understanding of the nuanced interconnections that exist between ourselves and our environment.

One Response

Jim, you are an incredible teacher. I would love to be teaching alongside you. I am a 30-year retired veteran of teaching students in grades 3, 4, and 5. Just reading your description of project-based learning in your classroom made me wistful for the days I was designing instructional units. Your students are fortunate to have you in your lives. As you mentioned, in light of the questionable policies being developed by our present EPA, we desperately need to be producing environmentally literate and civic minded citizens.