For the last 15 years, we have collaborated to create standards-aligned integrated learning models for environmental literacy and the arts in order to support issues of justice. Using these models in the classroom has ignited our students’ imaginations. In early August 2020, as we approached an uncertain school year, we sat down to reflect on our thinking and the approaches that have helped us grow as educators whose mission is to encourage students to love and take action to support our natural world.

Trena: Ana Raquel, one of our core ideas is to create multiple entry points for students to express their learning. We use the strategy of teaching environmental literacy principles through hands-on experience and the arts to foster deep learning over time so that learning is experienced in the same way that environmental scientists investigate. This strategy allows students to feel like they have an important role to play in the learning process, elevating their ideas and voices.

Ana Raquel: Paulo Freire said, “Children read the world before they read words.” Each year I take students out on an ocean research vessel in the San Francisco Bay. During this trip students get to see firsthand how real scientists are studying the ocean. They get the chance to work side by side with these researchers. They use tools and get nose to nose with creatures in specimen tanks. After a few of these trips, I started to see a pattern with early language learners—the experience made them go from being quiet and reserved to sharing pages of facts in follow-up meetings. I also realized that when we all have an experience together that we can draw from, it equalizes the playing field. For example, people are touching tools as an entry point to vocabulary words like salinity. And in the classroom, experts who come in to share live research from the field give my students immediate access to environmental justice information that is relevant and current before it’s published.

Once our students create meaning with new information and decide what matters, they are then purposefully offered multiple ways to communicate about that topic: writing a song, a rap, or a poem; designing an interactive outdoor learning station; or making puppets and creating a performance. As they use their creations to teach back to the community, students cultivate art skills, life skills such as leadership, technology fluency, communication strategies, and more. The real assessment is when students teach what they know to live audiences and answer real questions rather than complete racist/classist standardized testing.

Trena: Hands-on/minds-on deep understanding takes time. Elongated learning, or learning about a theme over time, moves away from being exposed to a concept with one or two discrete lessons to deeply understanding big concepts about our environment. Projects often take a whole school year, so students begin to understand what it feels like to be a researcher in the world, building attachment to the creatures and natural systems they are learning about. Ana Raquel, I have seen some of your students build a kind of holy reverence for native bees as they study them throughout the year. Having that kind of experience is when real, deep care takes hold for kids.

Story 1: When J came to my fourth grade classroom, we were starting a year-long study of native bees with Trena and Dr. Gretchen LeBuhn of the Great Sunflower Project. J was a so-called struggling student all through elementary school. But he became so attached to the bee project that he became one of the class experts. We saw over the year that diving deeply into this study built his confidence in amazing ways. He learned how to deeply observe the details of the natural world. He became a leader in our marine debris project and led other peer educators. In middle school, after a jog around the neighborhood, he came back home to report to his grandmother, “Wow, the world is so beautiful.” In his first two years of high school, J did internships that focused his passion for nature: working with a master gardener in Oakland community gardens and completing wilderness training in Bay Area parks. Now J is tending a garden of his own.

Trena: We can’t use the old models anymore, because they are highly inequitable. That’s what Freire was fighting against. Teachers are often curious on their own and have a perspective of inquiry. When they share their interests and perspectives with students as a model for participatory learning, they create the constructivist learning environments that Friere talked about, in which cycles of inquiry start with students’ and teachers’ collective curiosity and excitement begins to build collective actions.

Ana Raquel: Freire had the belief that dialogue is a deeper kind of listening. So the first step in setting up a participatory research process is building trust with your group, large or small. The deep listening piece allows students to come forward to name oppression and share experiences that made them feel unsafe in the past. There has to be some serious work around safety and trust-building for a healthy classroom. But this trust-building work leads to meaningful collective action.

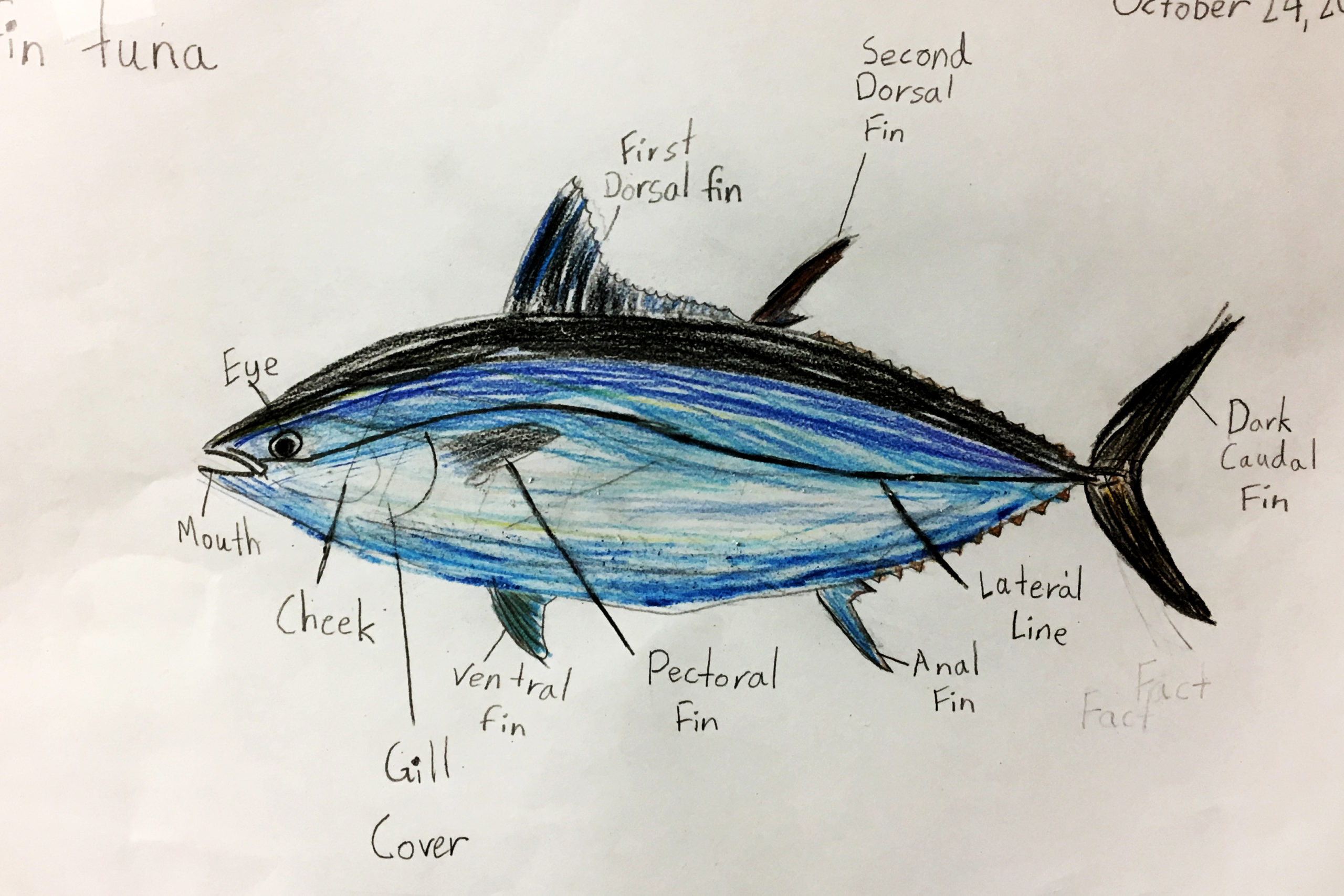

When you create a cooperative research space, students help each other read articles, ask each other for help when they need it, and feel safer about writing. Our class is a think tank in which everyone has gifts to offer. When we start with a living lab space like a school garden or even a fish tank, we lean in together and generate questions. We find the answers together by reading, dialoguing, illustrating, building models, observing, and talking to experts. We study scientific illustration techniques by John Muir Laws, because he struggled with feeling excluded by schools and, sadly, children relate to what he talks about.

Story 2: D was a student who was a loner in my class when it came to engaging in group work. This was very stressful for her. When we began the marine science and bee projects, we needed someone to manage our microscope station. My strategy was to have her be a resource for other students because she was brilliant and quickly learned how to use a microscope. Becoming an expert created a space of security for D. From that point on she was able to work seamlessly with others in small settings, and she quickly became well respected by the other students in the class for her expertise.

Trena: In participatory research, the arts and collective expression are important pieces. Ana Raquel, the plays and animations your students have created about native bees, the important and urgent messages they have constructed about why the wetlands are so important to our lives—these collaborative processes become really engaging teaching tools for others, and they help your students coalesce around urgent local environmental issues that are important to our community. All the songs and raps students compose for these events, the puppets they figure out how to construct in order to help tell the story—allow your students to embody the learning. This facilitates even deeper understanding.

Ana Raquel: Artists are not celebrated enough in the academic world. When we are assigning class jobs and I ask which students want to be the class artists for our research projects, there is always a sigh of relief. When we sit down to write scripts or raps because the children just learned that bees are a keystone species and that they want to protect bees, the voices and brilliance of students who are often not heard in more traditional learning settings emerge strong and clear.

Trena: It is important for students to be in conversation about their learning with experts. Dr Gretchen LeBuhn has been collaborating in your classroom with students since 2011! It is amazing to have a local environmental scientist make that kind of commitment to a learning community! That collaboration has brought so much knowledge and empowerment to students across the school.

Ana Raquel: This moment is an opportunity to educate young people in a unique way. Let’s line up global climate change and pollution experts in the field and have them present research directly to students via Zoom. Let’s not wait for articles and books to be written—let’s get students a direct pipeline to urgent information now. When we intentionally put dynamic activists, scientists, artists, designers, and fired-up teachers who are people of color on the mic, young people will see themselves in the future of this work.

As veteran educators, we propose to reframe this moment as an age of invention, with our students leading the way. Today’s generation of students will have a unique ability to create radical change, to break from systems that have oppressed their learning for too long, that have abused our earth and natural systems without care. We believe our students will become the solutionaries we have been waiting for. Let’s create change now by trusting them and lifting up their brilliance. Let’s go!

2 Responses

Hi. I just wanted to give a shout out to the Marine Science Institute (MSI) in Redwood City, who owns the Robert G. Brownlee Research Vessel. I first learned of MSI when my then kindergartener took a field to their facility. As a chaperon parent, I was extremely impressed. The Marine Science Institute has been educating San Francisco Bay Area students about the environment through a Marine Science lens for some 50 years. From school field trips out on the bay and tide pool discovery classes to researching the the SF Bay sloughs by using canoes to an enriching summer camp, MSI has something for every age group of our community….young and old! Check it out at http://www.sfbaymsi.org and start learning about the importance of our local environment, it’s habitats and creatures today! And check out my favorite fish, the Starry Flounder!

I love that this work combines art, science and environmental justice. It’s awesome that you encourage students to engage in this manner and that they demonstrate talents that may not show up in a more traditional classroom setting.