“I need a glue gun!”

“Should we use black or white paper?”

“Think about the angle.”

“Let’s try putting the foil here.”

“Should we seal it completely?”

If you were at Bay Farm School in Alameda on June 12, 2019, you would have heard these phrases coming from teams of teachers who were designing, building, and testing solar ovens. It was the first day of the Alameda Elementary Environmental Literacy (AEEL) Institute, the last in a three-year series that has brought teachers together with scientists for a week each summer to explore how to use environmental literacy as a lens for science learning, and how to integrate science with other subjects K–5 teachers teach in their classrooms. In the previous two years of AEEL our sessions explored local natural and human habitats, examined interactions among earth systems, studied climate and the greenhouse effect, and dug into the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and California’s Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs). This year 32 teachers, an agroecologist, and a solar engineer spent the week planning integrated lessons and tackling questions about how energy and garden systems work using NGSS engineering principles.

Now, back to the solar ovens. The first day was all about solar energy, starting with an engineering challenge to create an oven that could cook s’mores with the sunlight available on the schoolyard. After struggling with designing and testing the first oven models and figuring out what worked well and what didn’t, both the power of the sun and the value of the iterative NGSS engineering process was very clear! As we savored the last bit of chocolatey marshmallow, we started thinking about other aspects of solar energy. The oven-building activity lends itself to a wide range of discussions about how to capture and harness solar energy, how it is used around the world, and how renewable energy is different from burning fossil fuels.

Like the sun, we often take for granted the energy that powers our homes. What is really happening when you flip a light switch or turn on your microwave? Do you think about where that energy is coming from?

Most of us probably hope that it comes from a renewable source like solar or wind farms, or maybe a hydroelectric dam, rather than the more traditional fossil fuel-based energy generating plants. But what we might not think about is the challenge of moving energy from source to consumer. That is the job of the electric grid, as we learned from our solar engineer Mohini Bariya. As she beautifully explained, the grid is a complex web of energy movement that must consider demand and availability, as well as how to accommodate the challenges of shifting to newer, sustainable sources of energy and novel loads such as electric vehicles. To explore this process, Mohini led us through a simulation in which we matched energy sources in California with the demand from different kinds of users.

After exploring solar energy for cooking and its use in the electric grid, we began to think about energy and agricultural systems. It turns out that almost a third of the world’s biodiversity resides in the soil. These organisms contribute to a complex ecosystem below our feet that depends on organic matter, supports our agriculture systems, and is an important site for carbon storage. Under the guidance of Yvonne Socolar, a graduate student in the field of agroecology, teachers designed and refined experiments to study organic matter in soil and think about its connection to energy flow and soil biodiversity. Of course, above ground biodiversity is also important. Think pollinators—without them plant productivity would plummet! Using a card game to simulate pollinator-plant interactions, Yvonne gave us a deep look into the value of native pollinators and the connection between them and soil health. To an ecologist, it is not surprising to find that soil health, organic matter, pollinator diversity, and plant diversity affect the health of our gardens.

A real-world connection to local issues and action can be a powerful motivator for students.

On the third day of the institute, we left the school setting and got out to explore local environmental and sustainability issues, and to learn about related actions being taken by local government, community groups, and businesses. We heard from local practitioners about Alameda’s own electric utility and energy challenges, the Alameda Climate Action and Resiliency Plan, how the city manages runoff with rain gardens and bioswales, and how to join the Green Schools Challenge. Later in the day we toured a local LEED certified business campus and visited two local engineering operations, one using solar energy to power seafaring sail drones and the other building submersibles, both in support of ocean research. There are so many ways for teachers to build on what they heard and saw and, if this quote is any indication, I think they will: “The local field trips were amazing! I can’t wait to continue researching and to share these resources in my classroom.”

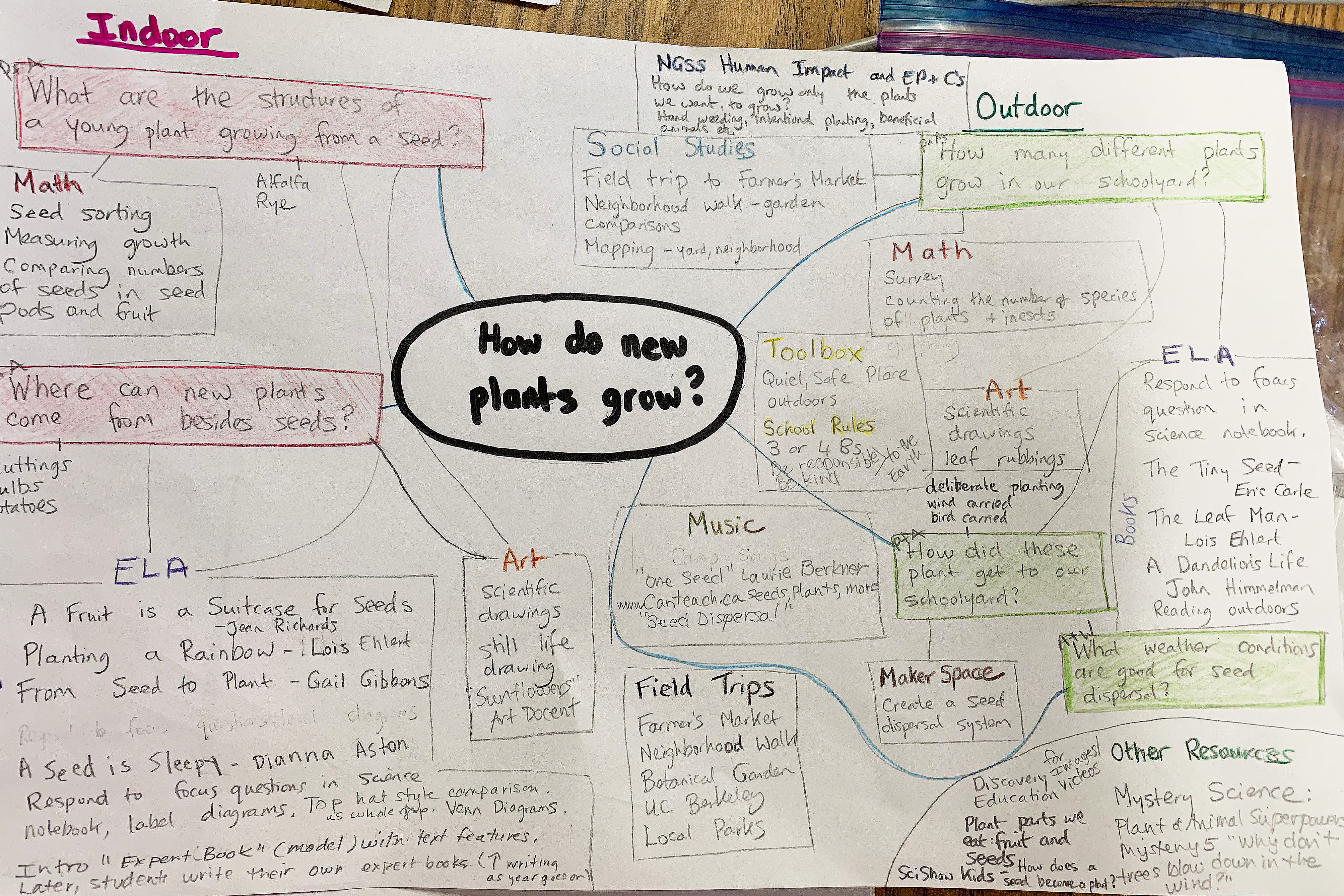

Finally, teachers built their own integrated lesson sequences. Everything we did on the first three days was designed to provide experiences and resources for using environmental literacy as a lens to create integrated lesson sequences. The planning started with mind maps centered on a science unit and an environmental connection. Building from there, teachers incorporated math, language arts, social studies, art, and outdoor activities that would mutually reinforce learning goals. Time for planning is essential for teachers to bring environmental literacy to their curricula, and there was a lot of enthusiasm for the process and the outcome. It was exciting to see the work the teachers had done and what they were taking away at the end of the institute. But it was a bit sad too, closing the last day of our three-year journey. One teacher’s reflection on the 2019 AEEL summer institute helps us feel that this program was successful in what we hoped to accomplish.

“It helped me see how much there is to learn, wonder, and analyze outside, without needing a whole lot of materials. Simply studying natural resources such as sunlight, temperatures, water, and wind can be so interesting! I feel more confident to wonder with my students and to learn together.”

Perhaps the best thing to say now is thank you: to Ten Strands, the Alameda Unified School District, and the Lawrence Hall of Science who supported the Bay Area Science Project and the University of California Berkeley Natural History Museums to create the program; to the graduate student scientists from UC Berkeley, businesses, and local environmental practitioners who shared their expertise and experience; and most especially to the participating teachers who made it all work by bringing their teaching skills, interest, and curiosity to everything we did.