On April 21, 2020, the California Subject Matter Project (CSMP) held a virtual environmental justice charrette. The charrette brought together CSMP leaders, environmental justice organizers and scholars, and student leaders with the goals of exploring the following questions:

- What is environmental justice?

- What does teaching for environmental justice look like in practice? How does it compare and contrast to what we teach in specific disciplines?

- How might we best integrate environmental justice into the work we are already doing in professional learning and in classroom instructional programs?

The charrette follows earlier work done by the California Environmental Literacy Initiative (CAELI), which includes representatives from three of the CSMPs, at a meeting held in May 2019 focused on environmental justice. Originally scheduled for October 2019, the charrette was delayed because of wildfires and then pushed online in response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. These two seemingly disconnected issues can actually be connected to and through the central issue of environmental justice. Many marginalized communities experiencing environmental injustices are also those most vulnerable to the disparate impacts of wildfires and disease as a result of the interlocking relationships and inequities produced by race, class, the environment, and public health. As such, the issue of environmental justice is more relevant than ever.

Welcome, introduction, and breakout

The virtual event began with a welcome from CAELI project director Karen Cowe, who shared the goals of the initiative, explained Ten Strands’ partnership and the role of CSMP support in environmental literacy work, and expressed gratitude to Breakthrough Communities for the technical assistance and planning support they provided leading up to the charrette. Karen’s welcome was followed by an introductory speech by CSMP executive director Claudia Martinez, who recognized the ongoing commitment of CSMP toward environmental justice and environmental literacy in education. Charrette participants then broke out into groups to share with one another their prior knowledge and experience around environmental justice.

Keynote

Environmental education advisor José González gave the keynote speech of the day, addressing why environmental justice should matter to educators. José framed his speech in terms of “nature-rich just-communities,” purposefully tying together nature, justice, and equity to produce a more holistic vision. Part of environmental justice work is thinking about this big picture: identifying where environmental injustices come from, who is privileged and who is marginalized, and who has been involved in the environmental justice movement and activism from the start. These topics raise issues of racial- and class-based privilege, which require recognition of the constant, sometimes invisible, fight of indigenous peoples and people of color for environmental justice. Education is integral in the fight for environmental justice because people need to acquire knowledge in order to act effectively. Empowering students through environmental literacy thus provides youth with the tools they need to address both local and global environmental issues.

First panel discussion

The first panel discussion addressed the question “What is environmental justice?” This panel consisted of three individuals involved in community work around environmental justice: Ei Ei Samai, culture designer of the Samai Group; Sammy Nuñez, executive director of Fathers & Families of San Joaquin; and Bernadette Austin, acting director of the Center for Regional Change (CRC) at UC Davis.

Ei Ei began by talking about how life is “groundless” for those experiencing various modes of oppression and discrimination and how this groundless state ties into the future of work. Because of increasing automation, shifts in the labor market, and the lack of a social safety net, among other issues, today’s youth are facing an increasingly volatile future, which they can only prepare for by learning to deal with these ongoing uncertainties. In the realm of design, Ei Ei suggested shifting from human-centered design to life-centered design, using systems thinking and decolonization as frameworks to shift practice and take socioecological issues into account.

Sammy continued by presenting on the community work being done in Stockton, California, first identifying the inextricable relationship between environmental justice and racial justice and how these issues have been manifested historically and institutionally via redlining, urban renewal policies, incarceration, and more. As a result of directly experiencing the negative impacts of these structural practices, low-income Black and Brown communities are the most intimately knowledgeable about their local environmental injustices, and so should be meaningfully involved, rather than ignored, when addressing these environmental hazards. As Sammy stated, “Anything about us, without us, is not for us.” Sammy went on to provide examples of collaborative community work, from indigenous environmental stewardship practices, to youth participatory action research, to geomapping and citizen science.

Bernadette rounded off the panel with some concrete examples of and resources for environmental justice education. Bernadette offered suggestions on how to engage students in environmental justice issues in their own communities, using media like PhotoVoice to document local environmental discrepancies such as differences in park access and maintenance. In terms of resources, she suggested publicly available data maps such as CalEnviroScreen 3.0, data sets like the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, and the CRC’s toolkit for youth participatory action research. Bernadette concluded by reminding the audience to follow principles of environmental justice in their teaching: engaging with communities who are already involved and impacted by the issues students are learning about should provide a mutually beneficial relationship in which educators and students collaborate with community organizations and offer their support while learning.

Second panel discussion

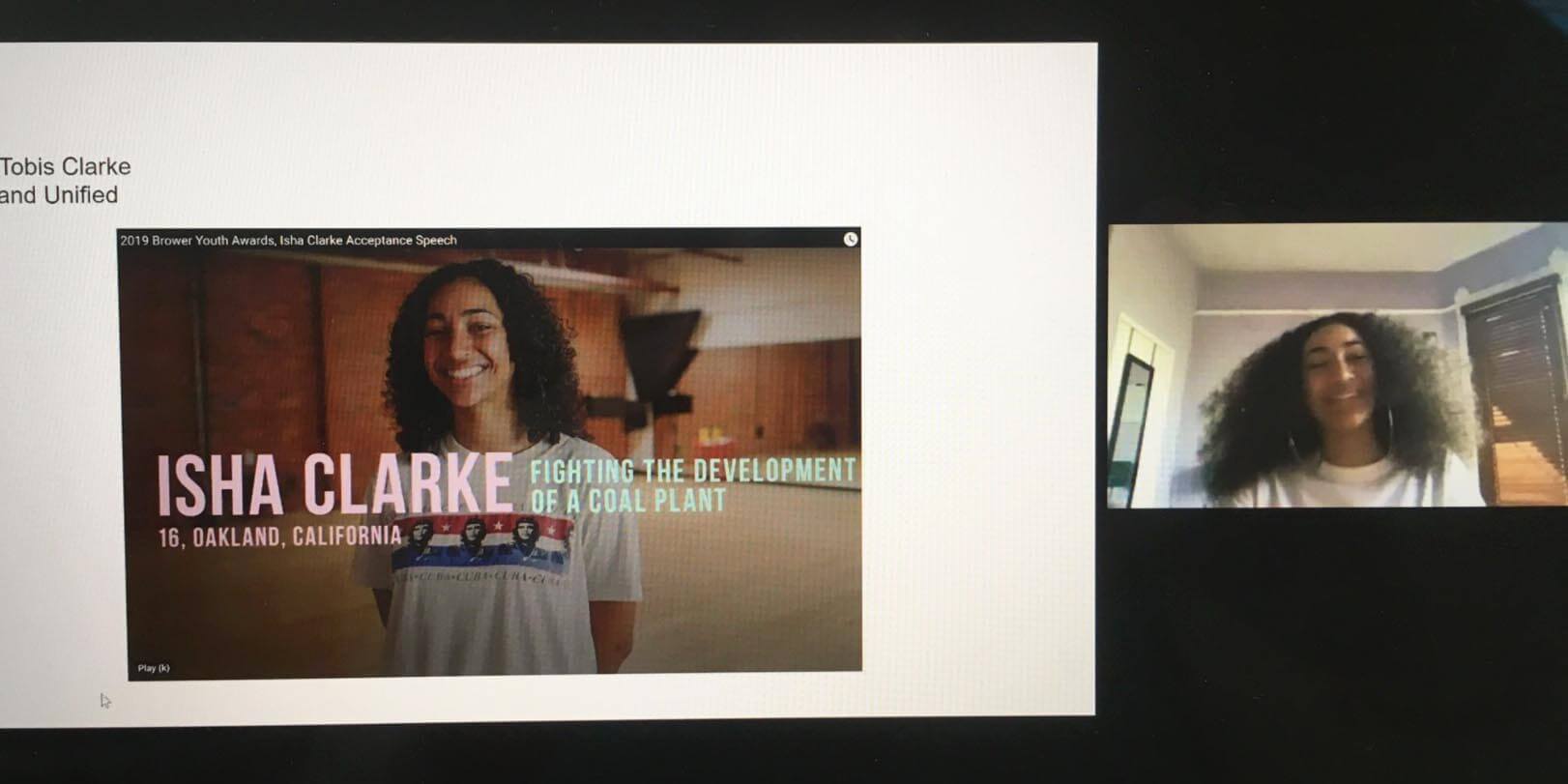

Following the first panel’s broader look at environmental justice, the second panel focused on education, addressing what teaching for environmental justice could look like in practice. The panelists included Isha Tobis Clarke, a student and organizer from Oakland Unified School District; Juanita Chan, STEM coordinator for Rialto Unified School District; Ana Thomas, a teacher at Peralta Elementary School; and Andra Yeghoian, environmental literacy coordinator for the San Mateo County Office of Education (COE).

Isha began by discussing how schools currently fail to address relevant life skills and issues, and how the separation of subjects prevents interdisciplinary and intersectional thinking and understanding. Isha’s call to action centered around climate justice, which she called “the most encompassing movement” because climate change is a result of white supremacy, racism, and colonialism and these issues can be addressed only by breaking down all systems of oppression.

Juanita followed by identifying issues of equity and access in school districts, the limited power of individual educators in making structural changes, and the need for environmental literacy to be fully integrated into the regular curriculum so that it is available for more students. Juanita suggested building yearly grade-appropriate lesson plans and involving parents and wider communities as ways to start to address these issues.

Ana’s presentation built upon Juanita’s suggestions by calling for student-centered learning in which educators meet students at their level and context of understanding, build on topics of interest, and use hands-on activities to keep students engaged and learning.

Andra then provided a perspective from the COE level. She discussed the need for all educators and administrators to do their part in incorporating environmental justice into students’ education because there is no singular position involved in environmental justice work and because environmental justice naturally lends itself to integrated learning.

Overall, environmental justice learning presents opportunities for students to learn about and participate in their own communities and can be applied across various contexts and subjects, encouraging community engagement and critical thinking. It is clear that environmental justice is a relevant, interdisciplinary topic that should be a part of K–12 education and that this integration can only be meaningfully implemented if educators are provided with the proper professional learning opportunities and structural support.

Conclusion

After a final Q&A session, the day ended with a short speech from Dr. Maria Simani of the California Science Project, reminding all participants that this charette marks only the beginning of a long conversation around environmental justice in environmental literacy education. She highlighted the development of CSMP environmental justice action plans by the nine subject-matter projects as next steps.