Take a moment to go outside and inhale a whopping breath of air. Do you take in a breath of fresh air or do you in fact take in a breath of fresh pollution? The answer to this question lies in where you are taking in this precious air. As science educators, we have a duty to address environmental principles and concepts and to ignite student conversations that discuss environmental racism and environmental justice explicitly.

Human impact on the environment not only involves individual habits or obvious polluters, but also the government regulations, city planning, and legislative measures that dictate our everyday lives. Unfortunately, the roots of systemic racism continue to manifest in these types of measures. For example, diesel truck routes pass through West Oakland, California. The 21,000 residents living in West Oakland are predominantly Black and from lower-income households. This situation can ignite a series of the types of questions we want our students to consider. Who created the truck routes? Was air quality taken into consideration when the routes were planned? Were the residents of Oakland considered in the decision to run the routes through this specific part of the city? Was there diverse representation at the decision-making table? Having students consider the multiple facets of environmental situations like these is pivotal in their understanding the root causes of environmental racism.

Do we have time to discuss environmental racism?

The answer is an absolute yes! If as environmental science educators we are not talking about environmental racism, then we are only presenting one side of a multifaceted and deep-rooted problem. Additionally, the field of environmental science typically lacks a diversity of voices to convey the message. We must consider having more representative voices in the field so that the diverse range of students we are teaching can see themselves in this work. That is why we should highlight environmental scientists of color. Dr. Tyrone Hayes, for example, is a world-renowned endocrinologist from the University of California, Berkeley. He specializes in researching the effects of pesticides and herbicides on amphibian populations. He expanded his research to include migrant workers and how the rates of reproductive cancers within this population increase with exposure to pesticides. His work contributes to our understanding inequitable distributions and impacts on different people, which is critical when discussing environmental issues.

How do we teach about environmental justice?

Arguing from evidence and constructing explanations are two very key science and engineering practices in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). As science educators, we must be able to present real-world and authentic examples that enable students to create scientific arguments about issues that directly impact their lives. For example, one teacher presented the case of shipbreaking and how Western countries disassemble and recycle their ships in countries like India and Bangladesh. The industry provides jobs for the economies of these countries, yet the environmental impacts are detrimental to their populations. This type of real-life case study can be presented to students and, based on the evidence, students can craft their arguments about the problem and possible solutions.

Phenomena-based instruction is integral in teaching the NGSS. At STEM4Real, we encourage our teachers to create what we call culturally responsive phenomena, phenomena that sparks not only curiosity but also discussion that incorporates cultural identities. This type of instruction goes beyond simply showing examples of environmental scientists of color and their work. This instruction actually encourages our diverse students to participate actively in their learning. Achieving authentic student engagement involves presenting phenomena that speak to the lived identities of our students. They have to see themselves in the problem, and their voices should be encouraged and validated within the discussions.

We have crafted five steps to creating phenomena-based, antiracist environmental science lessons for your classroom:

- Find your phenomenon: Ask yourself how the phenomenon can ignite curiosity and environmental justice. Investigate local issues that affect the school and community adversely, such as water quality, air quality, or urban heat issues. There are many environmental issues that can be translated to sociopolitical issues.

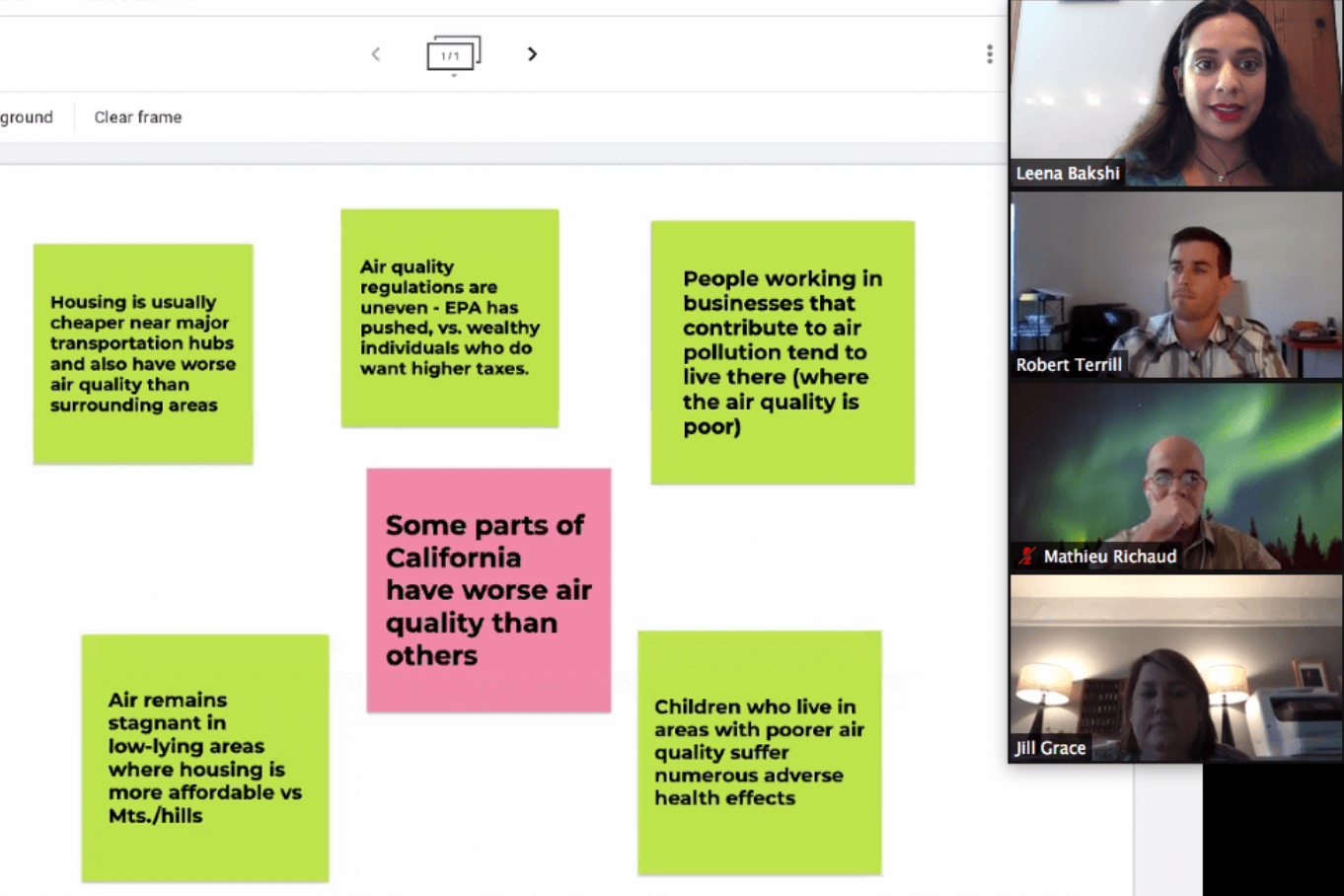

- Generate questions and observations: Present the inequitable environmental issues to your students, and ask students to generate questions and observations. Teachers can set the stage for the unit or lesson by starting with a brainstorming session of student-generated questions.

- Explore students’ communities to find evidence: Ask students to consider the phenomenon within the context of their community. It is the responsibility of the educator to present these situations to students so that they can weigh the evidence themselves. This step grounds students in crafting their arguments. Tap into the local communities of our students and elicit examples that provide students with first-hand experiences. This allows students to understand the multiple perspectives involved when discussing complex community issues.

- Create a culture that facilitates social justice: A good resource for discussing social justice is the Social Justice Standards at TeachingTolerance.org. This resource can help facilitate building community within our classrooms, anchored in the pillars of identity, diversity, justice, and action. Another good resource is Ibram X. Kendi’s children’s book Antiracist Baby, illustrated by Ashley Lukashevsky, (Kokila, 2020), which serves as a guide for antiracist norms at all ages. He writes, “Open your eyes to all skin colors.” Norms like this reiterate inclusivity and set the stage when discussing social justice issues.

- Do the science: Engage in active and hands-on science activities that bring the phenomenon to life. For example, when looking at water quality, have students boil different samples of water and then test for purity, pH, and clarity.

To help implement these steps in classrooms, STEM4Real, K12 Alliance, and Ten Strands teamed up to design environmental science and NGSS units for high school students. Our collaboration focused on the inclusion of climate justice and culturally responsive teaching in the sequences. Intentional coaching for each cadre also focused on making explicit references to opportunities that highlighted racial and climate justice.

When engaging in social justice work, it is vital as educators to obtain ongoing professional learning focused on antiracism and social justice. This goes beyond a single workshop. This is a continual journey on which we must dig deep into our own implicit biases and educate ourselves on sociopolitical injustices. As we learn about the relevant phenomena, we can educate not only ourselves but also our students on environmental issues that create societal disparities. Take time to continue professional learning on antiracist teaching practices that address racism, implicit bias, and microaggressions in the classroom. Identify and connect with other equity-driven teachers or staff members and form committees to consistently advocate for social justice, diversity, inclusion, and equitable access in all areas of environmental science curriculum and instruction, #4Real.