It’s January. The holidays are over. A new year has begun. It’s the time when people who love the cold or snow are relishing winter while folks like myself are pining for the light and warmth of spring.

It’s no coincidence the first month of the new year is named January. Janus was the Roman god of beginnings and endings and therefore gates, doors, doorways, and other passageways. Often depicted as having two faces, Janus simultaneously looks to the future and the past.

As I look back at last calendar year, I smile….a lot.

I was first introduced to the Education and the Environment Initiative Curriculum in late 2013 by Kami Wong, a dedicated employee at CalRecycle’s Office of Education and the Environment. I had the honor of teaching Kami’s daughter (now a junior in high school) and her son who is currently in my 6th grade class. She sent me an email one day saying I should take a look at the EEI website, sign up for a webinar, and try teaching a unit. She got the feeling I’d love the curriculum.

She was right.

After a webinar with an EEI Teacher Ambassador who walked me through the curriculum and answered my questions from the comfort of my classroom after school one day, I requested and soon received my first EEI unit: 5.3b Changing States: Water, Natural Systems, and Human Communities. It took just one lesson to realize I was teaching meaningful content that was engaging and respectful of student learners. The text was well written, the activities well thought out. My students were thinking deeply—we were no longer simply “covering” standards” but taking the time to discuss and work with big ideas as they relate to the environment. The epic California Drought was in the news a lot last year, and my students and I were able to discuss it at great lengths and grasp its effects on our reservoirs, ground water, and food prices.

Our next unit was 6.6b: Energy and Renewable Materials Resources: Renewable or Not? During one of the lessons, I used an LCD projector (and photons of light rather than paper photocopies) to project a series of cartoons. Students worked through a series of questions to aid them in deriving the deeper meaning as it relates to the environment and natural resources.

One cartoon in particular stood out: an image of a father talking to his son in front of a stand of coniferous trees saying, “One day son, all of this junk will be mail.” “Why are they saying these trees are junk, Mr. Bentley?” asked one of my students. The discussion that ensued highlighted a few different things. Many kids understood the cartoon was referencing “junk mail.” All of my students received junk mail at home, and none of my students viewed trees as junk. Most of my students never stopped to consider that tossing junk mail into the recycle bin was equivalent to disposing of trees!

Tossing trees in the trash? That’s ludicrous, right?

Students latched onto the cartoon and analyzed the various levels of meaning. One person’s junk mail is another person’s advertisement. Mail can always be recycled if it’s not wanted. But the energy used to create junk mail that’s unwanted cannot be recycled. Cutting trees and making paper adds carbon to the atmosphere and promotes global warming. Junk mail is annoying. Junk mail sometimes has catalogs with things we want. Trees are consumed to create mail. But trees are renewable.

The trajectory of the lesson took a completely different turn. My students were using the ideas they had been studying and were trying them on for size, discussing junk mail as it relates to natural resources. “How much junk mail do people get each year?” one student asked.

That led to a flurry of Google searches and millions of links related to junk mail and how to reduce it. We found several websites that for a fee will take steps to remove individuals’ names from direct mail marketing lists in order to cut down on the amount of junk mail received annually.

I should pause to let the reader know this lively discussion was taking place in the second week of December 2014, a time when most kids’ minds are clouded with thoughts of Christmas and winter vacation and presents.

One student raised a hand and commented: “Mr. Bentley, I know we get a lot of junk mail and that uses a lot of paper. But think how much wrapping paper gets used at Christmas!” A new round of comments and talking erupted. And moments later we had two experiments crystalize before our very eyes.

First, our class should bring in their holiday waste—the wrapping and boxes and tissue paper—from both Christmas and Hanukkah. Second, our class should collect all our junk mail for one calendar year to see just how much we actually receive.

The Holiday Trash Sort quickly took on a life of its own. We contacted our principal to ask if we could use our school’s gymnasium to sort our waste. We contacted our city’s integrated waste department to train us on what constitutes trash, recyclables, and reusables. We invited our mayor to bring his holiday waste. All we needed was for students to show up.

And boy did they show up. On December 26, 2013 we had 25 out of 28 families bring in their holiday detritus. We had originally allotted two hours to sort and document the process with video cameras. It ended up taking almost four hours to complete the project. We created a time-lapse video of the experience that summarized our findings on just how much waste we generate during the holidays. You can see the results for yourself by visiting our Vimeo channel.

I think the biggest take-away from sorting our holiday waste was this: most packaging can be recycled if we take the time and effort to sort it. We also learned that cardboard boxes with plastic windows need to be pulled apart. These “composites” are not recyclable

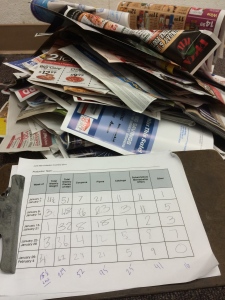

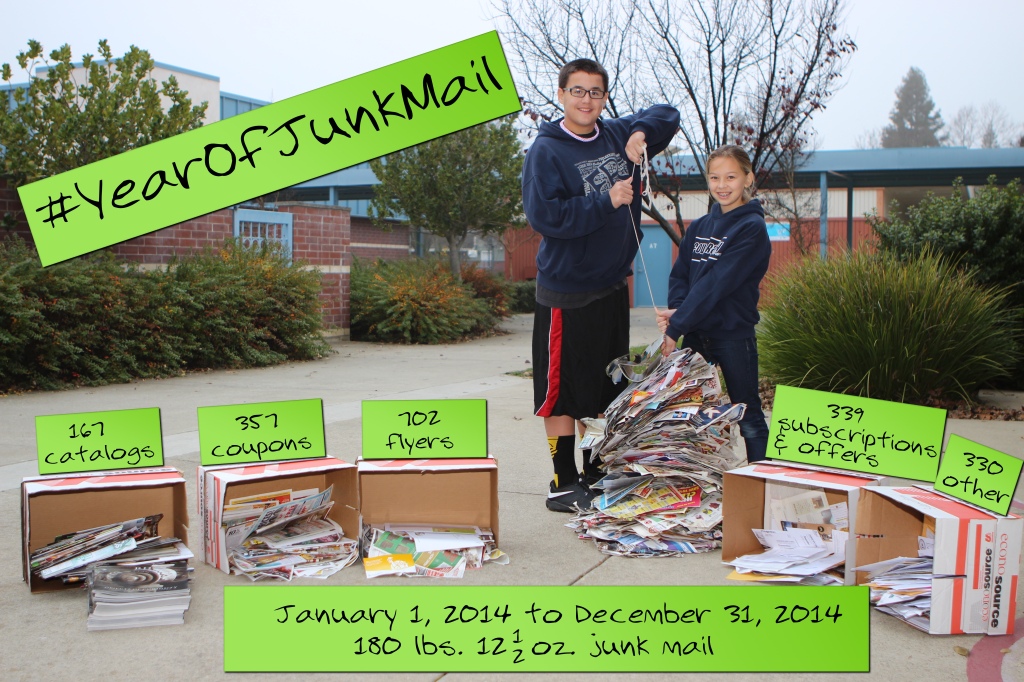

The junk mail experiment concluded December 31, 2014. For one year we weighed, sorted, and counted each week’s direct mail totals received by just one household—mine. My students were eager to bring in their mail as well, but we quickly did some speculative calculations and realized that 28 households’ junk mail would add up to a lot.

The results: last year I received 180 pounds and 12.5 ounces of direct mail marketing. We are now embarking on a project-based learning adventure to create a documentary film on the impact of junk mail on the environment. Students have broken up into teams to answer five essential questions:

- How can we define “junk mail?”

- What is the history of junk mail?

- What are the benefits of junk mail?

- Are there alternatives to junk mail?

- Is anyone doing anything about junk mail?

What started as a science lesson on natural resources has evolved into something much bigger than I had ever expected. Students are not only thinking scientifically, they’re viewing issues through multiple lenses: as consumers, as environmentalists, as historians, as writers, as researchers, as mathematicians, as documentary filmmakers, as storytellers, as activists. My students have stepped outside of a textbook and are engaging with real issues in our world that affect them right now and into the future.

It’s January. And as I look back at last year’s lessons and learning and look ahead at the calendar, I realize there is so much to do in so little time. My students and I find ourselves working with a sense of urgency.

“We’ve got to finish this film before we go to seventh grade, Mr. Bentley,” one student remarked in class this week, and I agree. We do need to finish our documentary on junk mail. My students and I are driven to work on big projects inspired by the EEI Curriculum because we want to share with the world what we’re learning and why it matters.

Trees aren’t junk. And the paper created from trees isn’t junk either. Natural resources have value and their harvesting and extraction have an impact on our environment. And while the need for a business or nonprofit to communicate with prospective customers or supporters is real, there are alternatives to the kind of direct mail marketing that generates 180 pounds of mail a year in just one household.

American biologist Barry Commoner is widely considered to be one of the founders of the modern environmental movement. In his 1971 book The Closing Circle he shared his four laws of ecology one of which states that “Everything must go somewhere. There is no “waste” in nature and there is no “away” to which things can be thrown.”

As my students and I explore big ideas together, I’m encouraged. My 6th grade students haven’t met Barry Commoner or read his book, but they have figured out—with the help of EEI—Commoner’s law that there is no “away.”

Janus, the Roman god of doorways. I believe my students are acquiring the skills and knowledge and habits of mind to make a conscious choice to open a new doorway to a greener future. I can’t wait to see what the future holds for us all.