Looking at the seventh-grade standards for history–social science (HSS), it is easy to have a panic attack. How is it possible to teach almost 1,500 years of history over five continents in ten months? This has been an ongoing struggle for many seventh-grade HSS teachers, and the result has usually been the same: a survey course, akin to Trivial Pursuit®, in which teachers highlight moments of history through a Eurocentric lens. After years in this spin-cycle conundrum, the emergence and integration of California’s HSS Framework in 2016 now gives teachers across the state the freedom to reimagine what the seventh-grade course could look like.

A teacher presentation at the 2019 California Council for the Social Studies (CCSS) conference about thematic teaching prompted us to consider a new approach. We had been integrating the HSS Framework into our instructional strategies and creating learning targets, but all were based on a chronological approach to history. We realized that a thematic approach allowed us to bring content about the environment, along with content about other important themes, into our instruction in a meaningful and deliberate way.

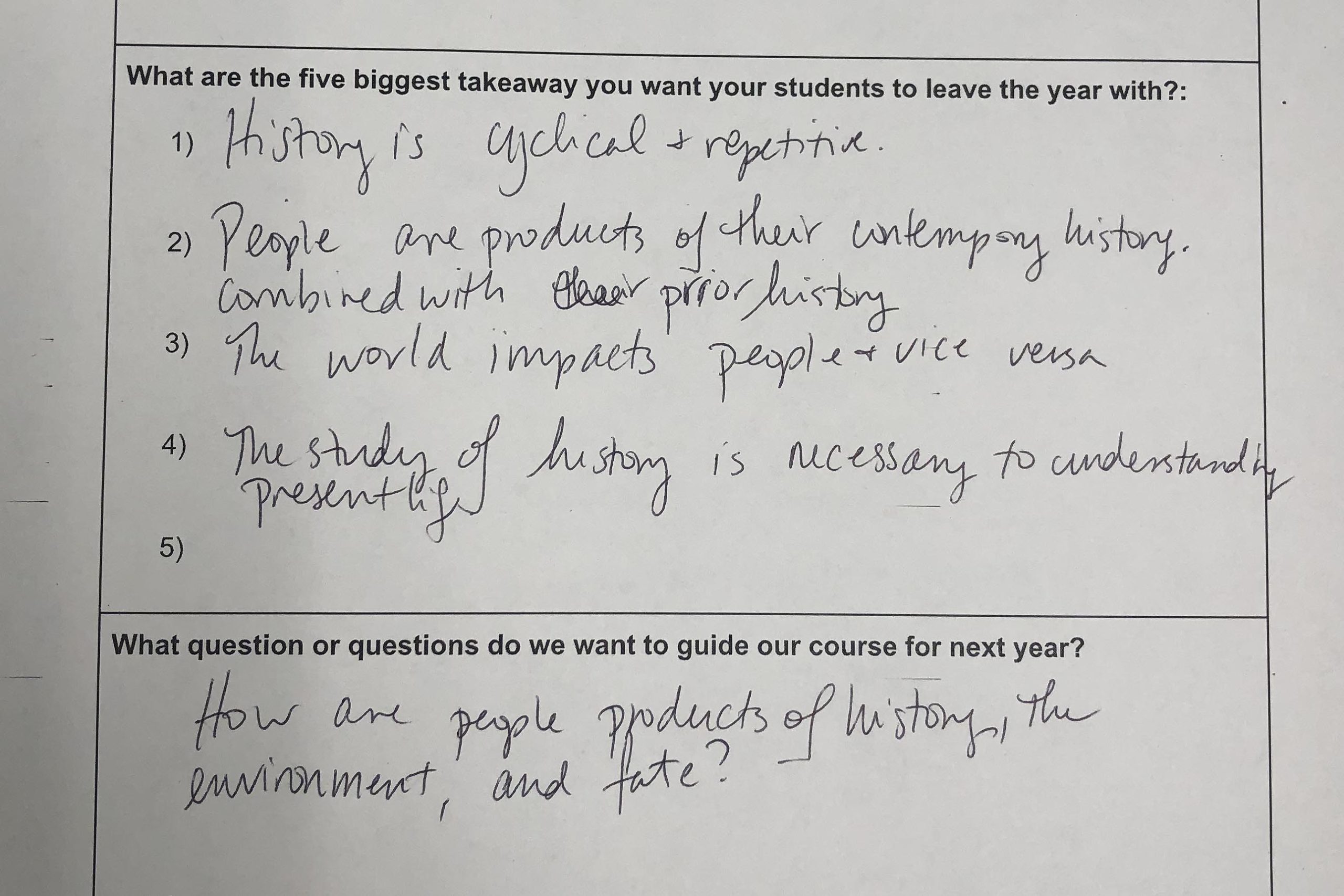

How did we get there? We began by asking ourselves about common historical themes in the seventh-grade material and by consulting the HSS Framework and our new curriculum. Gabriella even asked all her students to review the individual learning targets and group them into common themes. Taking all of this into account, we developed a course that incorporated seven themes: (1) human-environmental interactions; (2) rise of empires; (3) cultural belief systems; (4) order, chaos, and conflict; (5) societal transformations; (6) worlds of exchange; and (7) foundations of American democracy.

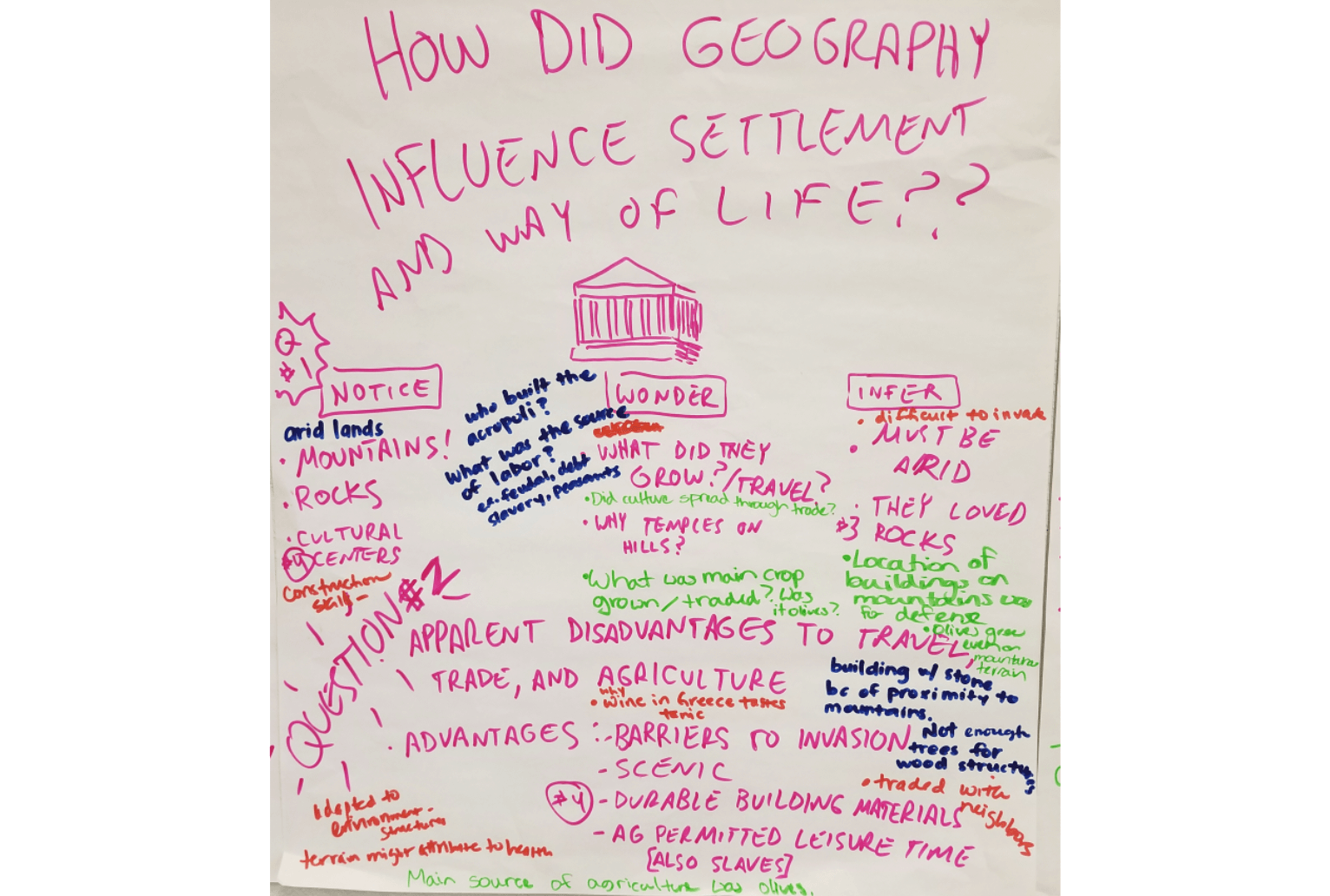

Last summer we began development of the human-environmental interactions theme for our course. As our first unit, we thought it paramount to provide students a relational understanding of their role in the environment. The HSS Framework encouraged an environmental lens, and we recognized that students need to conceptualize humans as part of their environment rather than as separate from it. With this in mind, we leapt at the chance to attend a UC Davis seminar in the summer of 2019, “Landscapes in History: Teaching with Primary Sources.” At the seminar we learned from subject-matter experts about teaching landscapes through the lenses of rural, suburban, and urban. We also received instruction regarding the role of indigenous people in the environment of the pre-Columbian Americas.

Inspired by the seminar, we developed our first unit to show the mutual dependency of humans on their environment. As we discussed how to develop the curriculum for students, we noted two important viewpoints: (1) the environment is both the setting and the actor; and (2) human manipulation of the environment is a historical constant, but human exploitation of the environment is a recent manifestation of this manipulation. For example, historians at the seminar spoke of the historic use of fire by indigenous people to manage and promote plant growth through controlled burns. Colonizers suppressed this practice, which to this day contributes to the massive wildfires California and the West routinely face. Because students are most familiar with modern slash-and-burn practices that can be destructive, they were surprised to hear that fire is not always a destructive force that pollutes but can be used as a tool to cultivate and protect important resources when employed with intention. To illuminate the difference for students, we juxtapose the historic use of slash-and-burn practices with their modern incarnations.

Recognizing the importance of incorporating content about environmentalism into all units of the course, we have consistently included geography content in every unit and have constantly spiraled back to what students learned in Unit 1 about the environment in order to deepen their understanding and reinforce key concepts. In addition, Gabriella made it a professional goal to incorporate California’s Education and Environment Initiative (EEI) curriculum into every unit to ensure that the environment remained both the setting and the actor. Both of us have kept the environment in the foreground, even incorporating the theory that natural climate change was a possible factor in the fall of the Roman Empire. Ultimately, the goal for both of us is that students know that when studying the social sciences, the environment is not separate from the human story but, rather, is intimately connected to it. If students can understand this, then they have a greater chance of understanding the role they play in history and on the planet.

Since this school year is the year of our great magical curriculum experimentation, we have taken great delight in discovering new ways to deepen the content for student understanding. Integrating the EEI curriculum, current events, ethnic studies, action civics, the environmental lens, the FAIR Act, and the HSS Framework has meant that our seventh-grade students are getting a rich world history experience that is applicable to other content areas and to their future education. Our ultimate goal is to share our scope-and-sequence model with our district colleagues and then, eventually, with other seventh-grade history teachers throughout the state. We were only half kidding when we told students and administrators that our goal this year was world domination.

One Response

I am a Middle School Social Studies Supervisor in New Jersey. Our teachers have been teaching World History Thematically for a few years, but continue to struggle with making sense for students. Are you willing to share your curriculum so we can see how ours compares?