The term confluence typically relates to the coming together of two or more streams or rivers. In California’s ever-evolving educational landscape, we can apply it to the coming together and weaving of instructional strategies and priorities that represent an unprecedented opportunity to expand the development of environmental literacy for all California students.

This was not always the case. In fact, when I first became engaged in implementing the Education and the Environment Initiative (EEI) in 2003, the reaction from California’s education agencies and key decision-makers was somewhat tentative at best. This response was understandable because California, like all other states, had just recently adopted statewide education standards and standardized student assessments. Therefore, it was rational for people in the K–12 system to wonder exactly how—and why—environmental literacy fit with all the new educational priorities that they were already responsible for implementing.

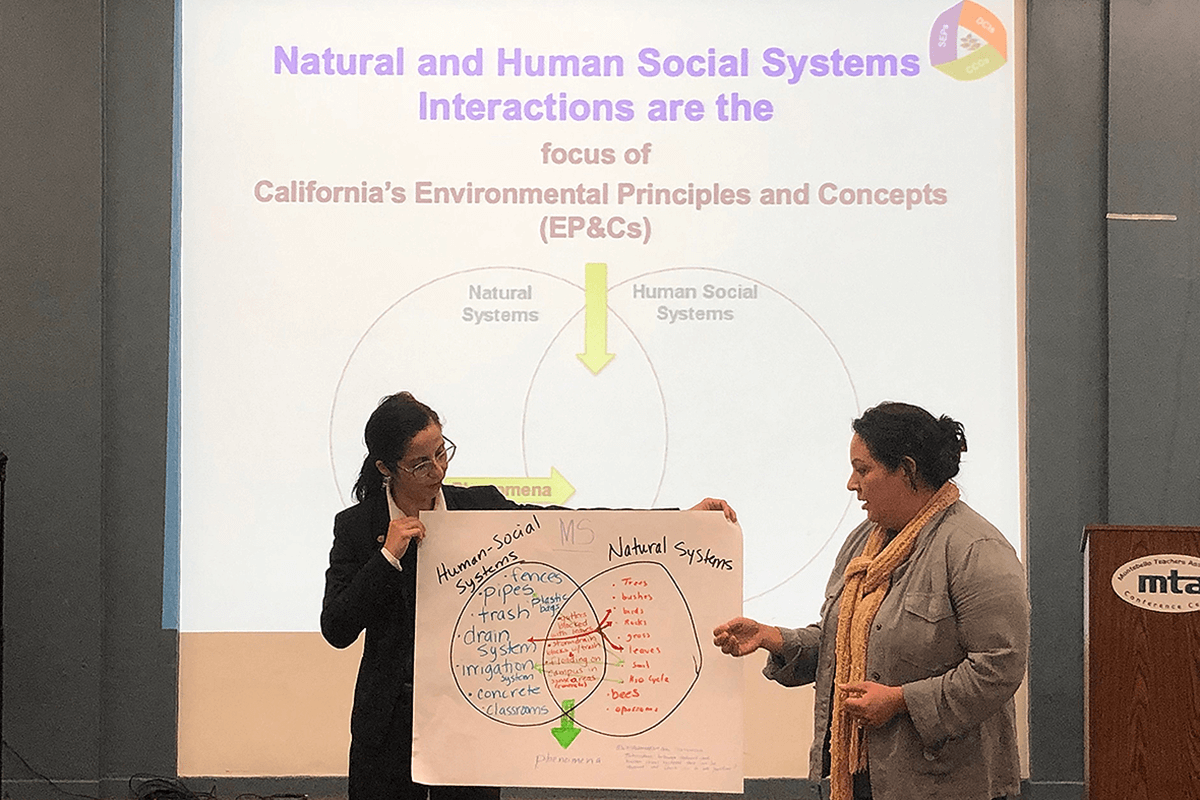

The landscape started to slowly shift with the development and adoption of California’s Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs) in 2004. Over the next six years, during the development, field testing, review, and ultimately approval by the State Board of Education (SBE) of the EEI Curriculum, relationships were built and education decision-makers began to recognize the importance of environmental literacy in preparing students to have “the capacity to act individually and with others to support ecologically sound, economically prosperous, and equitable communities for present and future generations.” (California Blueprint for Environmental Literacy)

At the state level, California’s education system operates on an eight-year cycle. The cycle starts when the SBE adopts content standards in each of the disciplines—English language arts, mathematics, science, history–social science, health, etc. Adoption of the standards is followed by the development of framework guidelines, drafting and review of curriculum frameworks, adoption of instructional materials, and the development of statewide student assessments for the major disciplines.

Following the adoption of content standards, each of the steps in this process offers an opportunity to make the case for strengthening the role of the EP&Cs and environmental literacy in standards-based instruction. Over the past six years, with Ten Strands support, I have been able to collaborate with the SBE and the California Department of Education (CDE) to take advantage of these opportunities to successfully:

- support inclusion of the EP&Cs in the frameworks;

- contribute substantial content for the Science (2016), History–Social Science (2016), and Health Frameworks (2019);

- participate in the instructional materials adoption process; and

- seek inclusion of the EP&Cs in the statewide student assessments—as of now, science is the only discipline that has been added to the statewide assessment system.

As a result of these efforts and some of the instructional strategies promoted in the most recent Science, History–Social Science, and Health Frameworks, the door is now open for California teachers and students to develop environmental literacy by exploring the interdisciplinary connections that exemplify the ways the world works—rather than the traditional discipline-specific strategies that have previously driven most classroom instruction.

I’m in a unique position of having read and contributed to all three recently published frameworks (Science, History–Social Science, and Health) and I’ve observed that there is a confluence of instructional strategies and ideas among them. In addition to these frameworks, CDE published Educating for Global Competency in 2016, which detailed findings and recommendations for improving and expanding globally-focused teaching and learning in California.

Although each of California’s new frameworks use slightly different language, they all call for instructional strategies that encourage student inquiry and civic engagement in their communities.

A few examples of the instructional guidance in these documents include:

- The Science Framework (CDE, 2016) “includes an emphasis on student inquiry. The classroom teacher serves as a facilitator to help students investigate scientific phenomena and principles of engineering through experiments and other activities that foster critical thinking.” This reinforces the CA NGSS (Next Generation Science Standards) emphasis on “real-world interconnections in science” which are best achieved through “hands-on and inquiry-based teaching practices.”

- The History–Social Science Framework (CDE, 2016) is guided by a focus upon student inquiry “where students ask questions, develop and support arguments, conduct independent research, evaluate interpretations and evidence, and present findings in a cogent and persuasive manner.” It supports student engagement with “inquiry-based learning, organized around questions of significance,” highlighting that the development “of a knowledgeable and engaged citizenry is the goal.”

- The Health Framework (CDE, 2019) calls on educators to “allow students to generate their own questions and to choose health-related activities.” It promotes inquiry and autonomy, stating that health education experiences should be “relevant and responsive to students’ interests, everyday life, or important current events,” include local environmental health issues, help students develop “the ability to analyze internal and external influences that affect health” such as air and water pollution, and “the ability to use decision-making skills to enhance health” including addressing issues around community health and environmental justice.

- The Educating for Global Competency report calls on educators to provide “opportunities for students to achieve global competence through content and skill development in history, geography, civics, economics, and other social sciences, especially in such areas as human geography, world geography, or contemporary issues.” It takes the position that “inquiry-based learning supports the attainment of disciplinary literacy while also facilitating progress toward the goal of becoming a more civic-minded global citizen.”

Considered together, these documents lay the groundwork for what, in most classrooms, represents a new way of teaching and learning. Interdisciplinary instruction that involves students in investigations of local, community, and global environmental issues provides them with opportunities to build and bring together their knowledge of science and understanding of history, economics, and social sciences—as well as communication skills, analytical and mathematical thinking, and an awareness of how people and government agencies make decisions.

Vitally important to these new instructional objectives is the idea of providing students with experiences that, as stated in the History–Social Science Framework, develop a “knowledgeable and engaged citizenry.”

Each of the subject areas approaches the objective of civic engagement through different strategies that support instruction in their discipline-specific standards; all seek the goal of “authentic engagement.”

A few examples of the instructional guidance in these documents:

- The Science Framework calls on students to develop engineering design solutions that engage “students with major societal and environmental challenges they will face in the decades ahead and gives them tools to design solutions to these problems.”

- The History–Social Science Framework highlights how “service-learning is an instructional strategy that engages students in real-world problem solving. Students work on community issues/problems that matter to them, applying critical thinking skills as they analyze causes and effects, discuss possible ways to address the issue/problem, and plan and execute service activities. The Framework outlines that “there must be an intentional link” between academic content, skills, and service-learning activities, which “can provide opportunities to make what is learned in class even more relevant to students.”

- The Health Framework calls on teachers to educate students “about environmental health, from both a personal and community health perspective, is a strand in the standards that continues from kindergarten through high school where students are expected to learn, among other issues, about the impacts of air and water pollution on health.” Further, it calls for rigorous “standards-based instructional methods and strategies [that] can support students in achieving more positive health-behavior outcomes and address the complex community and global health issues that impact the natural world and their personal health.”

- Educating for Global Competency includes mention of “opportunities for authentic engagement in topics of global significance,” and recommends that California schools “identify alignment and connections among global education, environmental literacy, and civic education.”

Although it will still require years to achieve the goal of environmental literacy for all California students, the confluence of instructional strategies across the frameworks is a crucial and never before achieved step in the right direction. Statewide efforts to raise awareness of how school districts, administrators, and teachers can use their local environment as a context for teaching and learning can help them achieve academic goals, build student inquiry skills, and demonstrate how students can be actively engaged in solving local environmental issues.

These approaches will ultimately move us closer to the goal of giving all students “the capacity to act individually and with others to support ecologically sound, economically prosperous, and equitable communities for present and future generations.”