Creative writing, poetry, and placemaking are all ways to connect complex scientific ideas and to explore relationships to the environment. Writing, and the various ways in which humans share ideas and stories, is also part of a longer tradition of storytelling. For thousands of years, humans have expanded the confines of language to define and redefine cultural values and to understand connections to places and community.

At a more practical level for environmental educators like myself, creative writing is also a versatile practice that can be included in any lesson. Creative writing helps students synthesize new ideas and use their imagination freely (Tok & Kandemir, 2015). Writing and the act of placemaking also enhance each other. For example, poetry is a great way for students to explore their connection to nature, express appreciation for a species or an ecosystem, and challenge paradigms that view humans as separate from nature. April is also National Poetry Month and a perfect time to celebrate the adaptable power of poetry across multiple subjects.

Before exploring resources and a few exercises around poetry and placemaking, I want to consider a few abstract concepts and definitions.

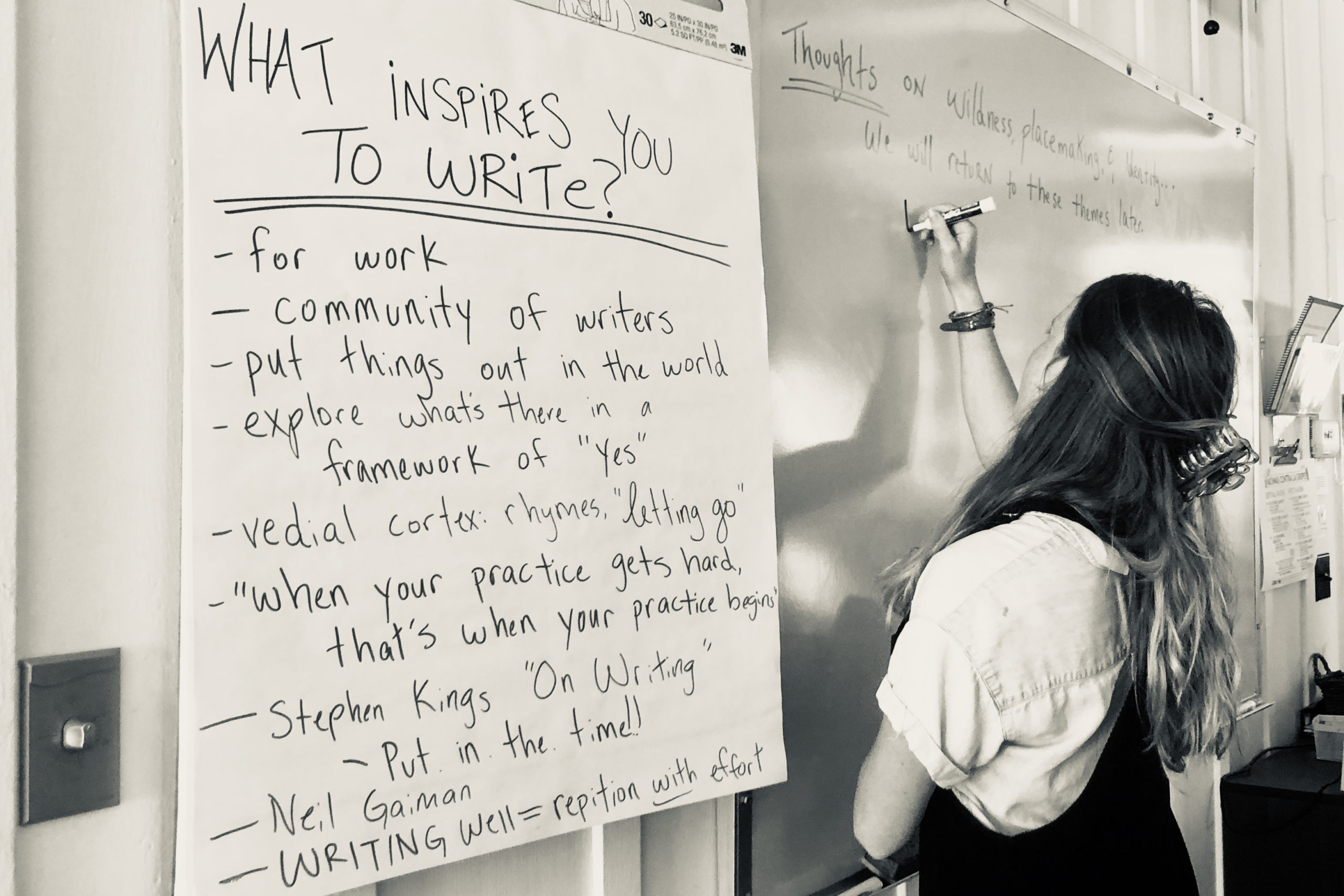

Why Writing? Why Poetry?

Since fictive language emerged around 70,000 years ago, humans have been predicting imminent futures and forming important relationships via symbols, shared beliefs, and stories (Harari, 2015). These messages, stories, poems, and so on, help us, individually and collectively, make sense of things, whether forming a sense of place or establishing cultural norms of behavior. For thousands of years, humans have depended on stories to bond with one another and to answer questions like “What is my role as a human on this planet?” Thus, to write and tell stories is to continue an ancient practice of making meaning of our surroundings.

As COVID-19 makes educators around the world rethink the educational system, it’s important to remember that storytelling and the various mediums in which stories are told are fundamental to the human experience. Looking ahead, integrating writing and science is one way for any educational program to teach environmental literacy. As Peggy Harte writes in her article “Using Environmental Literacy as the Through Line, All Standards All Students: A Focus on Equity and Access,” literacy and science can bolster each other by strengthening students’ reading, analyzing, and writing skills.

Poetry enters the scene as an emotional form of writing that centers the role of feelings. As many ecologists and writers have expressed, from Baba Dioum to Richard Louv to Rebecca Solnit, people write about what they care about. I’d extend this idea to argue that once students care about a place and feel connected to it, then they are excited to learn more deeply about it. Hence, play and poetry can be an excellent way to invite students to bond with their local places.

Poetry can also be adapted for all ages and is a way to unleash imagination, link new ideas, and create brighter futures for the world and people and the places we inhabit. That’s why programs like the River of Words® (ROW) out of the Center for Environmental Literacy and the Kalmanovitz School of Education are vital. Every year, ROW celebrates youth art and supports educators by offering a Watershed Explorer Curriculum, poetry writing guides, and a plethora of online resources.

Placemaking and Outdoor Education

During my years as a naturalist at Walker Creek Ranch, which is part of the Marin County Office of Education, I taught 20 to 25 students each week. Together, we explored the pungent bay forests, the warm grasslands, the alder-lined creek, and the wind-blasted rocks on Walker Peak. Our curriculum was student-centered and place-based, and writing was an instrumental part of it.

Poetry and placemaking can be integrated into any educational experience in ways that enrich students’ connection to themselves, to one another, and to their environment. Plenty of resources abound, especially with organizations like North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE) and curriculum from the Education and the Environment Initiative (EEI).

One recent webinar that expands the possibilities of poetry and placemaking is Small Marvels: Reflective Writing to Understand Place and Equity with Naamal De Silva, who emphasizes leading with wonder and exploring what is nearby. NAAEE, who offered this webinar, has so many resources to explore. The NAAEE’s 2020 virtual conference offers over 400 workshops, which are all available through September 2021.

If you’re an educator who wants to incorporate more creative writing into your daily teaching, but you are overwhelmed with the abundance of resources, I recommend starting small. Maybe introduce students to the haiku, a Japanese art form that often alludes to seasonality. If you can, explore a nearby place together with a few sensory-based activities. Then let students find a quiet “sit spot” to write a haiku about a beetle found in that place or a feeling the place invokes. Nature journals are great for students of any age, and observational poems can lead into lessons on local phenomena and community mapping. Observational poems can also be a gentle lead into a more extensive unit that focuses on poetry written by youth that addresses the need for climate action and environmental justice.

Introduce students in high school and beyond to publications like Orion Magazine for expansive environmental writing, or find ways to experience poetry with Krista Tippett’s On Being Project.

Reflection as Part of the Learning Cycle

Poetry and creative writing do not have to be the center activity; they can be explored at the end of a lesson. One of my favorite parts of the learning cycle, as explained by the BEETLES project, is the reflection stage. This is a learning stage in which students solidify connections they made during a lesson and in which educators get to witness any “aha” moments students have had. Often the reflection stage is the part of a lesson that outdoor educators drop because time is running low. It’s really important to budget your time to make sure there is time for a reflection, no matter how brief.

For example, after an afternoon of local exploration at a nearby park or schoolyard, end with a metacognitive prompt like “What observational skill or tip helped you notice something new today?” or a creative writing prompt such as “Write a poem about decomposition from the perspective of a fungus, bacteria, or invertebrate.”

The world of poetry and placemaking can be as expansive as imagination itself. Students and educators often just need a few ideas and permission to create new possibilities and connections with pen and paper.

References

Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Vintage Books. 2015.

Tok, Sükran, and Anil Kandemir. “Effects of creative writing activities on students’ achievement in writing, writing dispositions and attitude to English.” Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 174: 1635–1642. (2015). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/81948038.pdf