In May 2019, the California Environmental Literacy Initiative (CAELI) Leadership Council came together to have their second meeting, with a focus on environmental justice and environmental literacy. The goals for the day were to:

- develop a common understanding of environmental justice concepts and explore the interrelatedness of environmental justice and environmental literacy in K–12 education; and

- discuss and apply the lens of environmental justice to CAELI objectives and work to advance environmental literacy in California K–12 schools.

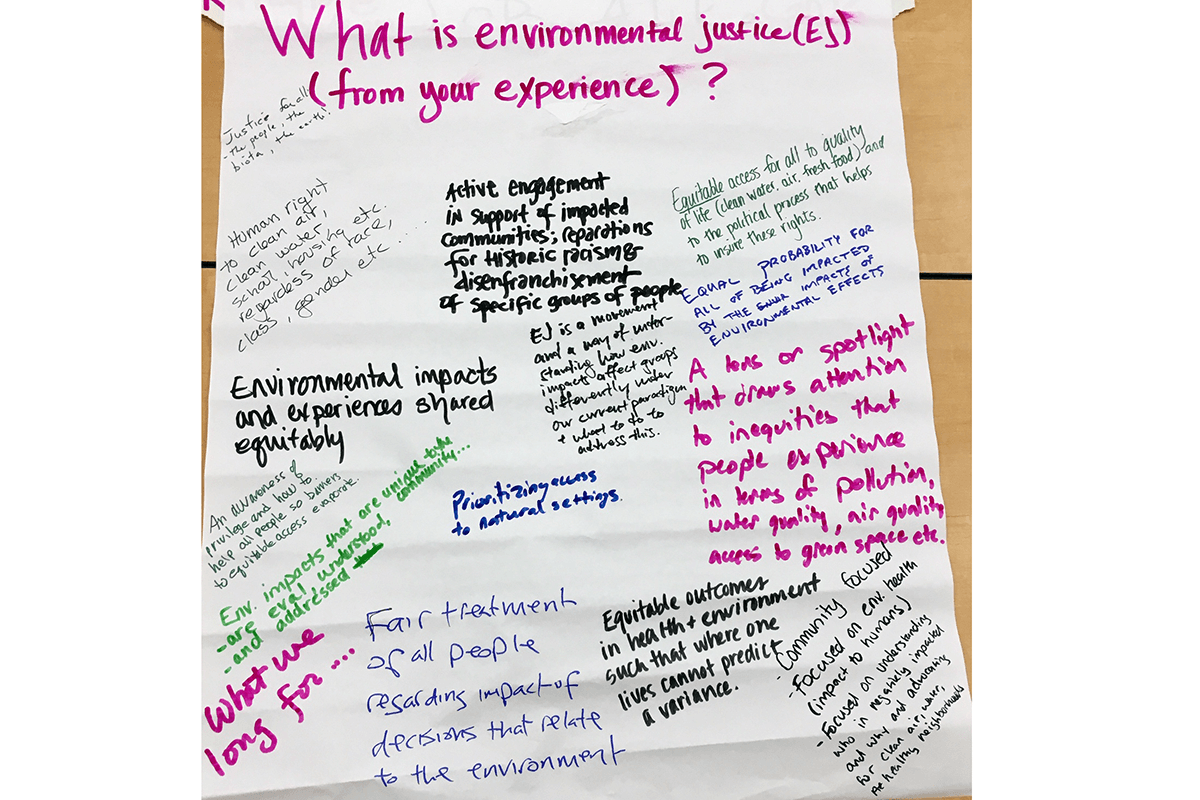

The day started off with breakfast and prompts posted on the walls around the room that asked participants to add their thoughts and questions about environmental justice, and how environmental justice and environmental literacy are connected. One thoughtful response stated:

“If environmental education doesn’t embrace and address environmental justice, then it’s not really environmental education—it is just a subset of topics and concepts about a part of the environment.”

The meeting began with opening remarks by CAELI project director Karen Cowe, covering the history of CAELI and recent work in regards to environmental literacy, highlighting A Blueprint for Environmental Literacy, the creation of the Environmental Literacy Steering Committee, and recent project work integrating environmental literacy into the California Subject Matter Project. The session then moved into a specific focus on environmental justice, led by a panel of guests with deep experience in the field.

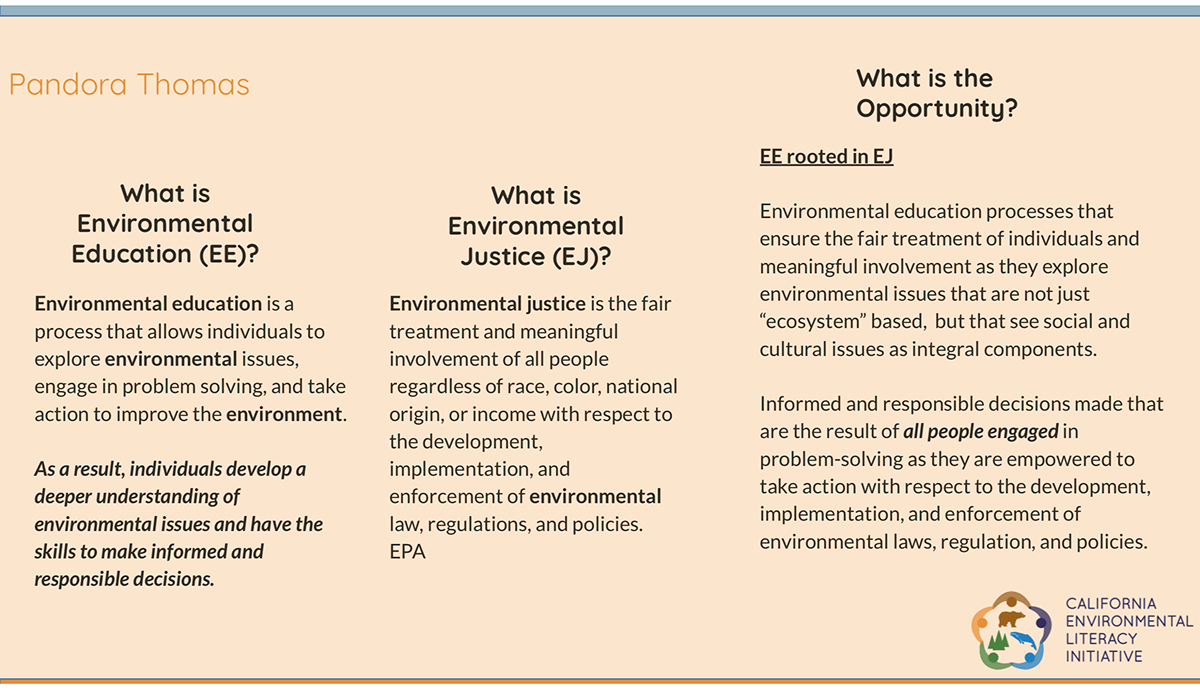

Pandora Thomas, a designer at the Urban Permaculture Institute, introduced the West African principle of Sankofa as a means to frame environmental justice. Sankofa is an Akan word—the literal translation of the word and the symbol is “it is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind.” Pandora highlighted how this is also inclusive of stories, and of grounded history—recognizing that people in the present are only here because of the people and history that were here before us. As an active practice of this, we recognized and acknowledged that the meeting was held on—and we were occupying—indigenous Patwin land. We also noted that we are all part of the environment, and stand on the shoulders of the activists who came before us and laid the groundwork for environmental justice.

To further frame environmental justice in the context of CAELI’s work, Dr. Gerald Lieberman gave a brief presentation on the California Health Education Standards, highlighting ways of exploring environmental justice and environmental literacy within those standards through the newly revised Health Framework. This includes recognizing that environmental factors, and how they differ across demographics and geography, are an integral part of both personal and community health.

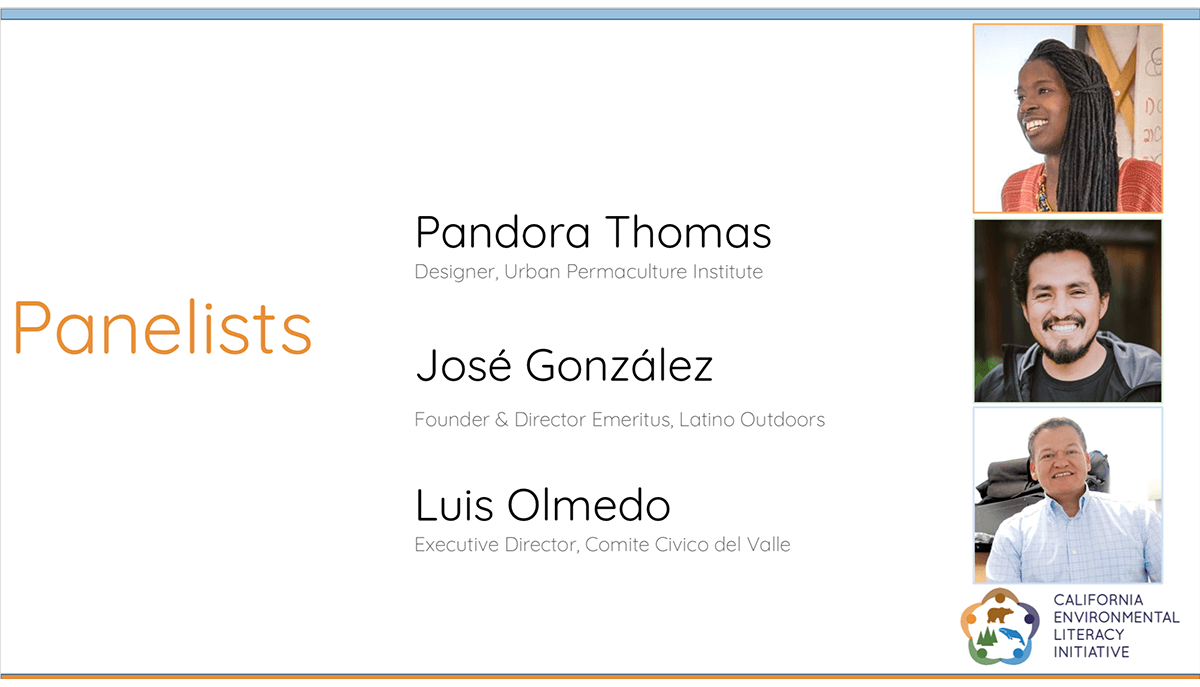

The meeting shifted to the panel of experts, comprised of activists and educators, to offer their perspectives on:

- what environmental justice is;

- what kind of work it constitutes;

- what its relationship with environmental literacy is; and

- what CAELI should keep in mind when supporting environmental justice as part of environmental literacy in K–12 learning.

The panelists included Pandora Thomas, José Gonzáles (founder and director emeritus, Latino Outdoors), Luis Olmedo (executive director, Comite Civico del Valle), and was moderated by Laura Rodriguez (director of programs, Youth Outside). The panelists first introduced themselves and their work, highlighting their personal connection to environmental justice through their family history, and how that history informs their work now. Included below are some of the questions and answers from the session.

What does environmental justice mean to you?

José and Luis both answered this, recognizing that environmental justice is a necessity that only exists because injustice in the form of disparate environmental impacts exist and must be fought against. Environmental justice work is personal—it can be dismissed as overly emotional as a result—and is being done largely by people of color who have been excluded from the mainstream environmental movement for not being white and wealthy.

Environmental justice often involves confronting structures of power, and necessitates working from the ground up, both inside and outside institutions.

What do you see as the relationship between environmental justice and environmental literacy?

All the panelists’ answers centered around the importance of teaching as a means of leading youth towards fighting for and achieving gains in environmental justice. Pandora asked participants to think about how the work being done by educators and nonprofits actually connects with the communities that are being impacted by environmental injustice—and look for ways to make a genuine connection that empowers people in those communities. José emphasized the importance of putting words into practice and empowering students, giving them agency to start making political, social, and environmental changes. Luis highlighted the importance of keeping youth involved and giving them the skills and tools they need to become leaders.

What should teachers, educators, and people keep in mind to effectively support environmental justice in schools?

Luis emphasized the need for advocates to truly believe in environmental justice and gain the support of those in leadership positions: those who hold institutional power can help affect system-wide change. José reminded participants that anyone can be an educator, and that education isn’t beholden to just spreading information.

In the case of environmental justice, it becomes integral for educators to meet communities where they’re at, understand the work that communities are already doing, and determine how to best support and supplement that work.

Pandora offered a system for participants to remember: MAGIC. This approach reminds educators of the need to meet communities where they’re at, foster empowerment and agency, and get buy-in.

- Messaging and framing

- Asset-based approach

- Growing leadership

- Inspiration

- Composing with our students

After lunch, Rena Payan (program manager, Youth Outside) facilitated a session where CAELI members and guests worked in small groups to think about power and privilege in connection with environmental justice. Participants were encouraged to think about the intersection of social justice and environmental justice, and identify how environmental justice issues tie into socioeconomic issues. Groups identified examples such as the NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) phenomenon, the locations of industry and toxic waste sites, and the further displacement of indigenous people to create national parks.

Attendees then reflected on and identified how they hold power and privilege, and what it means to leverage that power and privilege to help those who are systematically oppressed. As participants return to their respective positions in education and other environmentally-related work, they were encouraged to continue to ask introspective questions, become comfortable with exploring uncomfortable topics, and further commit to advocating for both social justice and environmental justice.

Attendees then reflected on and identified how they hold power and privilege, and what it means to leverage that power and privilege to help those who are systematically oppressed. As participants return to their respective positions in education and other environmentally-related work, they were encouraged to continue to ask introspective questions, become comfortable with exploring uncomfortable topics, and further commit to advocating for both social justice and environmental justice.

The meeting next transitioned into “job-alike discussions,” where participants were divided into groups based on their occupations in order to discuss environmental justice in the context of their organizations. The conversations centered around two questions:

- What does environmental justice look like for your area of work, and what are the implications and impact of this on educators?

- How will you articulate environmental justice as a fundamental part of environmental literacy?

The job-alike groups included state agencies, professional learning providers, county offices of education (COEs), school districts, and community-based organizations.

- Those who worked at state agencies talked about how environmental justice, in the form of equitable distribution of resources and initiatives, has become the way that agencies frame their missions. A number of them have realized that environmental justice work can’t just be pursued via a top-down approach, but has to be contextualized and informed by the needs of the communities being served.

- Those in professional learning talked about being inspired by students who were interested in environmental justice, and how to frame their work by thinking of the best ways to facilitate an environment conducive to learning about and working on environmental justice. Notably, one participant stated that environmental justice is not just the content being taught, but the way that environmental education is carried out.

- The COEs expressed that environmental justice looks different across counties, but is holistic in nature, thus requiring any environmental literacy staff coordinator to work directly under the superintendent to be most effective.

- Those who worked at the school district level had similar thoughts on how environmental justice initiatives would have to be done based on the needs and attitudes of communities and school district employees, and would have to be adapted to fit local audiences and context.

Through this part of the session, it became evident that environmental justice is inherently tied to the communities most impacted by environmental issues. This requires a set of principles and also a flexibility in approach in order to gain allies and effectively implement change. Although there is no one size that fits all, defining environmental justice and specific environmental justice goals, and setting up steps to achieve those goals, while sharing experiences on what works (and what doesn’t) will help educators across the state coordinate their environmental justice efforts.

In the final activity of the day, participants reflected on the session and identified what they had received and what they still needed on anonymous notecards. These notes will be used to provide direction on how CAELI moves forward on its work around environmental justice and environmental literacy.

Overall, the day provided a good starting point for how to think about environmental justice and implementing education around environmental justice, offering grounded examples from people who are doing environmental justice-related work and encouraging conversations among participants, who are already thinking about how they should approach environmental justice. The teaching of environmental justice as a part of environmental literacy is inherently interdisciplinary in nature, and students will gain a clearer picture by learning about the history and social aspects alongside the scientific components. CAELI’s May meeting on the topic of environmental justice and environmental literacy has established a foundation that can—and will—continue to be built upon in critical, interdisciplinary ways.