literate (adj.) “educated, instructed,” early 15c., from Latin literatus/litteratus “educated, learned,” literally “one who knows the letters,” formed in imitation of Greek grammatikos from Latin littera/litera “letter”

Literacy, as traditionally defined, describes the ability to use written language actively and passively; to read, write, spell, listen, and speak with some degree of proficiency. However, as we move further into the 21st century the argument that literacy is also ideological, a concept that exists within a specific context, has grown stronger, demanding that we consider literacy to include understanding that which goes beyond “one who knows the letters.”

And so it is with environmental literacy (EL). In California we now have a working definition of EL, thanks to the work of SSPI Torlakson’s Environmental Literacy Task Force (ELTF) and the product of that work, the Blueprint for Environmental Literacy (BEL):

“An environmentally literate person has the capacity to act individually and with others to support ecologically sound, economically prosperous, and equitable communities for present and future generations. Through lived experiences and education programs that include classroom-based lessons, experiential education, and outdoor learning, students will become environmentally literate, developing the knowledge, skills, and understanding of environmental principles to analyze environmental issues and make informed decisions.”

Nicely stated, and generally in agreement with what you’ll find across the nation as defined by the Partnership for 21st Century Learning, The Environmental Literacy Council, NAAEE, and a handful of states with environmental literacy plans of their own on the books. Using this definition (clearly an expression of the ideological and contextual evolution of literacy) quickly gives rise to a new batch of questions; prime amongst them, how is it accomplished?

A Carnegie Mellon University course, titled What is Environmental Literacy?, meant to provide students a solid foundation for EL, suggests:

“Environmental literacy is about practices, activities, and feelings grounded in familiarity and sound knowledge. Just as reading becomes second nature to those who are literate, interpreting and acting for the environment ideally would become second nature to the environmentally literate citizen. We take the idea of literacy a step farther, intending not only an “understanding of the language of the environment, but also its grammar, literature, and rhetoric.” It involves understanding the underlying scientific and technological principles, societal and institutional value systems, and the spiritual, aesthetic, ethical and emotional responses that the environment invokes in all of us.”

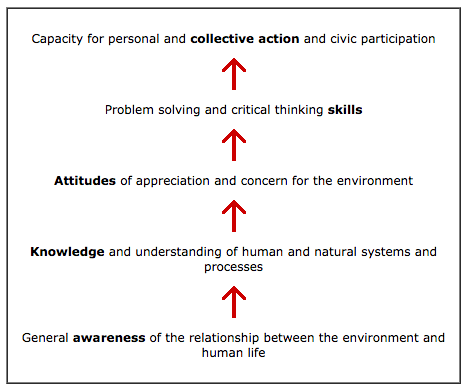

We’ll start with a basic tenet of learning that, regardless of subject, the process is cumulative. We begin with a foundational understanding and then build upon that, until finally we have the questions, the answers, and then more questions in an open-ended process of learning, discovering, thinking critically, questioning, and then learning some more. If we think about how to get to the desired end result of EL, the following visual aid is a good starting place:

The above, created by Campaign for Environmental Literacy to describe the Components of Environmental Literacy, represents a ladder. The ladder outlines five essential components of environmental literacy “designed as a loose hierarchy from the simple to the more complex, each building on the step below. However, as with many models, the steps overlap in real life. Most important to appreciate is that environmental literacy cannot be achieved without all steps of the ladder; achieving any one step alone is inadequate and will not result in literacy.”

The ELTF undoubtedly considered this model alongside a compendium of scholarly articles, expert opinion, and the vast experience and knowledge existent within the 47-member body. Their recommendations in the BEL are, like the ladder above, overlapping, and incorporate six overarching strategies that, when realized, should result in widespread K–12 EL throughout California:

-

Integrate environmental literacy efforts into existing and future education initiatives;

-

Strengthen partnership and collaboration among key stakeholders;

-

Leverage the State Superintendent of Public Instruction’s influence and build public awareness;

-

Implement changes to relevant state law and policy;

-

Ensure strong implementation through capacity building and continuous improvement; and

-

Develop a coherent strategy for funding environmental literacy.

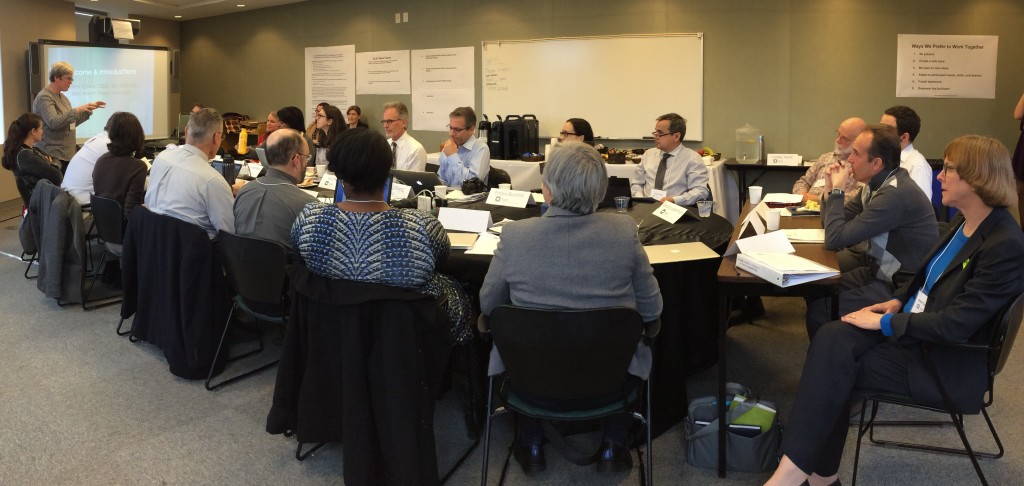

On January 20th the first meeting of the Environmental Literacy Steering Committee was held in Sacramento with Ten Strands, in partnership with California Department of Education (CDE), convening. With CEO Karen Cowe acting as interim Project Manager, and Founder & President Will Parish alongside Craig Strang (Lawrence Hall of Science) as co-chair, we gathered together with an extraordinary and committed group of members to begin the work of creating pathways to implementation of the BEL. Of particular note was how quickly the group gelled and began to collaborate, both as a cohesive body and as smaller working groups focused on specific overarching strategies.

SSPI Torkalkson’s office hosted the meeting, and the time Superintendent Torlakson took to share his vision of an environmentally aware and engaged student populace (as well as his thanks to the ELSC members) was appreciated and inspiring.

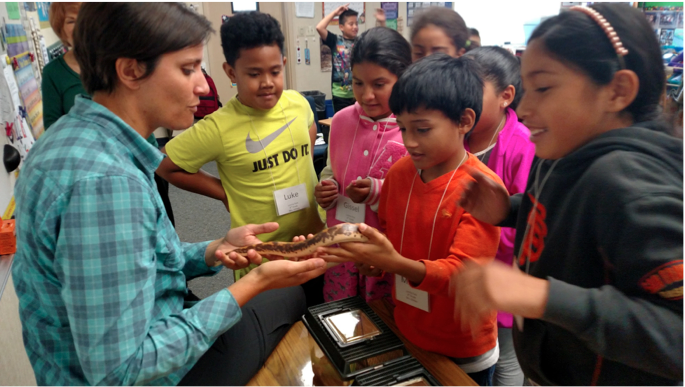

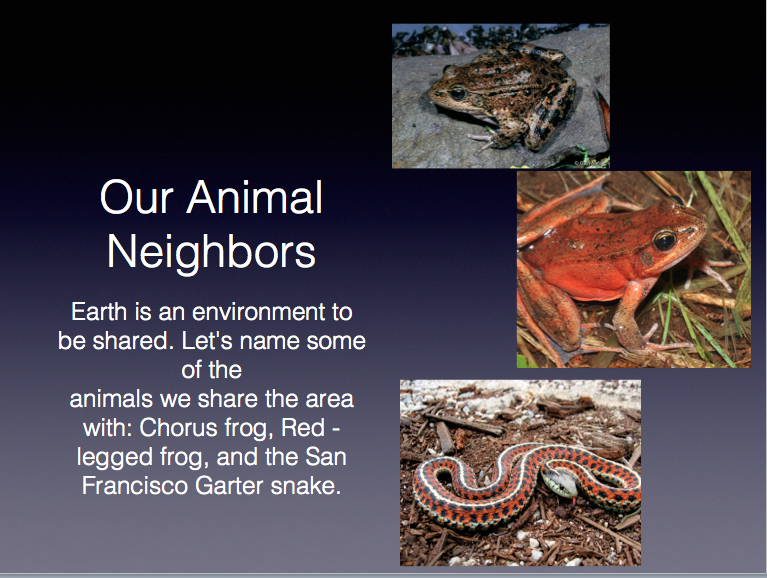

In keeping with Ten Strands own internal Treetops-Grassroots strategy, we couldn’t just stay up in the tree in Sacramento. The following week we headed to San Mateo for the San Mateo Environmental Learning Collaborative (SMELC) Capstone Institutes.

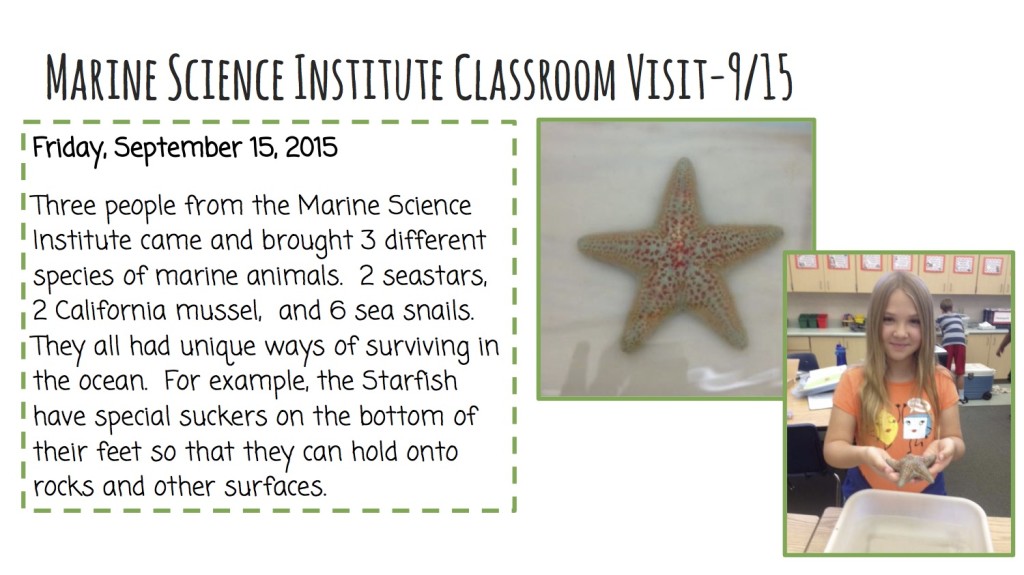

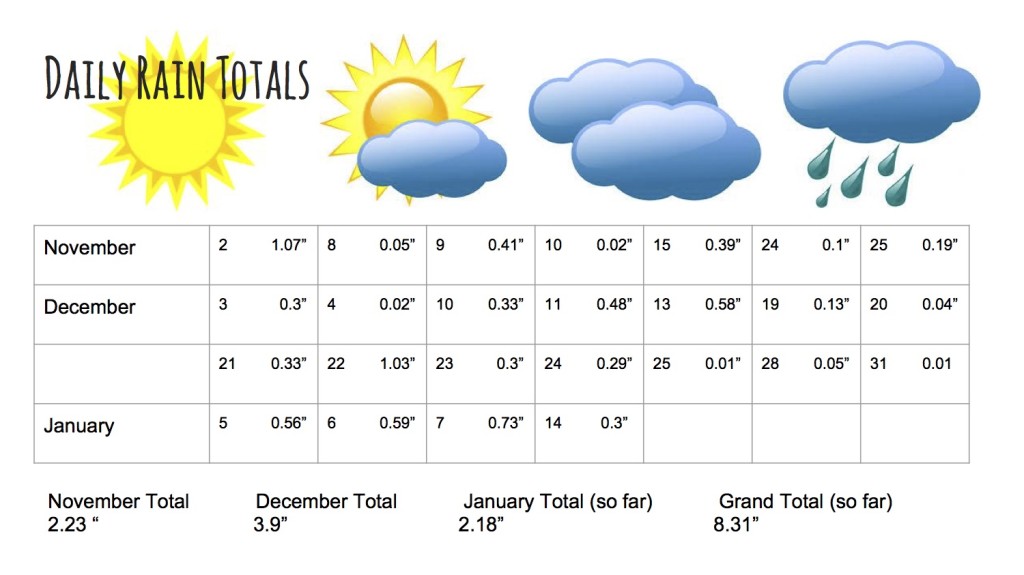

Teachers from our July and August summer institutes were in attendance on January 25 & 26 (once again at our partner San Mateo County Office of Education’s STEM Center) to share their experiences implementing the units of study they created for their classrooms. It was truly an inspirational experience listening to them present to their peers, nonformal ee provider partners, and program funders their NGSS aligned, environment-based lessons, student work, and service-learning projects. Many of the teachers serve as exemplars, demonstrating not only how BEL strategies 1 & 2 can look on the ground (integration of EL into education initiatives e.g., NGSS, and strengthening partnership & collaboration between stakeholders) but also as standouts in encouraging 21st century learning. In Getting it Right: What Effective Teachers Tell Us About 21st Century Learning, Helen Soule, P21 Executive Director, writes:

“I am continually awed by the teachers who overcome barriers of every kind to engage and inspire students to be learners for life. These teachers are the “connectors”, helping students bridge gaps not only in knowledge, skills and dispositions, but also making real world learning connections among school, home, and community environments.”

Among her examples of outstanding educators, “a California teacher connects her classes with the local state park to plan, research, and grow native plants to restore portions of the park to its original habitat.”

I smiled when I read Soule’s words, recalling a SMELC teacher’s presentation describing her unit’s focus on the Mission Blue Butterfly, an endangered species native to the Bay Area—and whose strongest remaining colony lies in her students’ own backyard on San Bruno Mountain. Students engaged in research and inquiry in their classroom lessons, then took a visit to the mountain to study the Mission Blues in their native environment. They identified possible reasons why the species has become endangered, and participated in critical thinking to determine possible solutions. They demonstrated concern for their endangered neighbors, and a capacity for collective action when they decided as a class that each student would take home lupine starts (Blue Mission caterpillars eat only lupine) to nurture into strong, healthy plants to be taken back to the mountain and transplanted to enrich the food source for the species. In one unit, this teacher hit all the rungs of the ladder referred to earlier in this blog.

What’s more, this was one teacher of nearly 70 that created and implemented units of study weaving science and the environment together in unique, cross-disciplinary, hands-on, and action-oriented ways. Rather than include photos from the event, I’d like to share a few slides that express teacher and student outcomes (and one teacher reflection that brought tears to my eyes):

The San Mateo Environmental Learning Collaborative doesn’t need to be a one-off; in fact it should not be. Continuation of this initiative can address strategies 1 & 2 of the BEL at the grassroots level while increasing teacher capacity and student engagement with minimal monetary investment. It is, in fact, critical that this type of work continue. According to the Task Force:

Limited data are available on the number of students in California with access to the types of learning experiences that build environmental literacy. Of the 520 California public school principals who chose to participate in a recent survey:

-

Only 13 percent indicated that their schools had successfully integrated environmental education into their curricula; and

-

77 percent replied that they spend $5,000 or less on field trips, professional development, and curricular materials for environmental education.

We are on the cusp of a unique and timely opportunity, with committed partners in the form of educators, state agencies, institutions, and individuals who are ready to act collectively in raising environmental literacy—and there are upwards of 6 million students in California eager to receive it. Whether you join us up in the tree or on the rich and fertile ground, please join us making an engaged, informed, and connected populace a reality.