The Problem I Had as a Middle School Science Teacher

As a student in the California public education system, I don’t remember a single time that we went outside to learn something. I do remember gazing out the window of Acalanes High School in the hills of the East Bay Area at the oak-studded golden hills and feeling trapped inside. I never learned the name of a single plant or animal living in the oak woodland ecosystem on the other side of that window. In recent years I have had a recurring dream that I’m back in high school, gazing out the window, when suddenly I turn into a bird. I fly out the window and perch on the top branches of the single redwood tree that grew on campus. The feeling is of freedom and expansive possibility.

I went to school in the ‘90s and early 2000s. California is now a leader in outdoor and environmental literacy, thanks to the efforts of Ten Strands and other organizations. My hope is that more students are getting outside for more time each year, but as a former middle school science teacher now myself, I know there are many barriers to expanding the classroom beyond the walls of the school building. One of those barriers is the lack of high-quality curriculum that integrates outdoor learning and is aligned to the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).

After receiving my master’s degree in science curriculum and instruction with a focus on outdoor science instruction from the University of Washington, I got my first classroom teaching position as a seventh-grade science teacher. I quickly discovered a problem. I wanted to involve my students in place-based, real-world projects. I wanted my students to be empowered to solve huge problems, like climate change and biodiversity loss. I wanted my students to study our local ecosystem for our ecosystem unit. The only published units available to me were based on ecosystems halfway around the world, and there were pretty much no complete science units that took the schoolyard as a learning space seriously.

I searched (and searched!) and could not find high-quality, place-based ecosystem units that embedded real-world projects that got my students outside of our classroom walls. There were some half-baked ideas but no high-quality units that provided all the materials I needed while meeting the high expectations of NGSS.

As I pondered how to create locally relevant storylines that integrated outdoor learning, I noticed an area of our schoolyard overgrown with English ivy, an invasive plant. Then I discovered native plants and habitat restoration. A light bulb turned on. What if my students could remove the ivy and plant native plants in our own schoolyard? But there was a much bigger window of opportunity here: what if the habitat restoration project could anchor a place-based ecosystem unit?

The Solution I Spent Years Developing and Field Testing

This was the seed of an idea that sent me on a five-year journey developing and piloting the Symbiotic Schoolyard Ecosystem Unit. I have now transitioned from teaching to supporting other middle school science teachers in restoring biodiversity to their schoolyards through my new website, Symbiotic Schoolyard. The unit has been through five years of iterative design with multiple rounds of feedback from the twelve pilot teachers who field tested it and three master teachers who reviewed it. The result is a high-quality, comprehensive unit with everything teachers need to teach.

The Symbiotic Schoolyard Ecosystem Unit

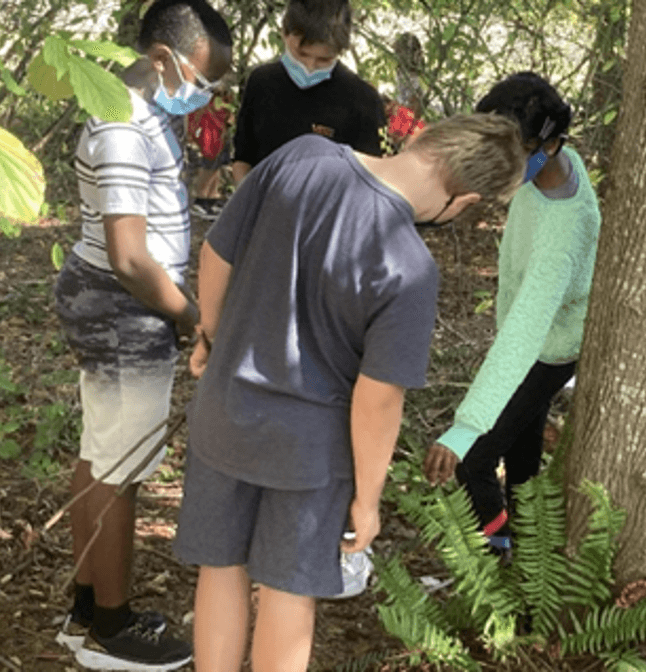

During the unit, students take on the role of restoration ecologists to figure out how to increase the biodiversity of their own schoolyard. There is a driving question that every lesson ties back to: How can we, as student restoration ecologists, increase the biodiversity of our schoolyard? Through eight weeks of hands-on, student-centered lessons both in the classroom and in the schoolyard, they figure out that native plant communities form the foundation of complex food webs. The unit meets the five middle school performance expectations for ecosystems (MS-LS2-1 through 5). In designing the unit, it was important to me that it was student centered, met the high expectations of NGSS, and was efficient and joyful to teach. My curriculum design approach is grounded in NGSS Storylines, three dimensional learning, and POGIL (process oriented guided inquiry learning). The majority of each lesson consists of students working in groups of four to complete an investigation or other hands-on activity (following a written guide) with the teacher acting as a facilitator (rather than a “sage on the stage”) moving between groups. One teacher recently said, “It’s the most exciting unit we do all year.” Another teacher told me that planting native plants in her schoolyard as a part of the curriculum has been the highlight of her teaching career.

A Locally Relevant Storyline That Can Be Taught Anywhere in California (with a Little Adaptation)

This is a place-based unit that can be used anywhere in California—or the country, for that matter. The way this works is teachers create a set of organism cards (including plants and animals) found in their region. The curriculum provides card templates and detailed instructions for creating these cards. The cards are used by students throughout the unit, and they are the key to localizing this unit to any ecosystem. It’s a “plug and play” that works really well.

The Symbiotic Schoolyard Ecosystem Unit Is Anchored by a Native Planting Project in the Schoolyard That Can Be Done with a Volunteer Expert Partner

The unit works with any kind of native planting project, including pollinator gardens, native landscaping, ecosystem restoration, planting trees, Miyawaki method, tiny forests, native meadowscaping, etc. As long as the planting project involves native plants, it will work with the unit. The schoolyard restoration site can be a lawn transformation, an area overgrown with an invasive plant, gravel, or even pavement (think native container gardening!) Any size restoration site will work: it can be a small area where students collaborate to plant just a few plants or a larger area where each student or pair of students plants their own plant.

The unit culminates in student groups designing a proposal to increase the biodiversity of their restoration site. Using the customized organism cards, they build an example of a food web based on native plants, compared to the simple food web supported by the lawn, invasive species, or pavement of their restoration site. Ideally, students actually carry out a native planting project as a part of Symbiotic Schoolyard, but some teachers may opt to not actually carry out the planting project, especially the first year they teach the unit.

Of course many teachers aren’t familiar with native plants in their region and don’t have the know-how to carry out a successful native planting project. This is where a community partner or volunteer expert partner comes in! This person can provide expertise on choosing a schoolyard restoration site, preparing the site for planting, choosing the right plants, planting, mulching, watering, and everything else involved in a successful restoration project. Ideally, this person not only advises but is present at all restoration days with students to ensure quality work. Finding this person can take some effort, but there are options. Ask your school garden teacher (if you have one) if they are interested in partnering with you to restore native plants to an area of your schoolyard, reach out to your local Master Gardener or Master Naturalist program, send an email to parents to see if any parents have experience designing and carrying out native planting projects, or reach out to your local California Native Plant Society Chapter or Audubon Society Chapter and find out if they have a member who would be excited to help you. If you want to become an expert yourself, you can take a locally offered class to learn about the native plants of your region and local restoration practices. These classes are becoming more popular and are often free.

You’ll want to involve your principal, head of maintenance staff, and volunteer expert partner from the beginning as you identify a schoolyard restoration site, plan, and carry out the native planting project. If you’re lucky, you will have a supportive administration, or you might have to persuade them of the learning benefits to students and the positive impact on your school community both during and after the native garden has been planted.

The Symbiotic Schoolyard Ecosystem Unit will work in any region and with any schoolyard. I work one-on-one with each Symbiotic Schoolyard teacher to make it work at their unique school and their situation. The Symbiotic Schoolyard package also includes two recorded professional development workshops that walk teachers through the steps involved in planning and carrying out the restoration project and provide training in the unit. The package costs $350 and can be billed as professional development or curriculum, but if school funding is limited or teachers have to pay out of pocket, the package is available at a generous sliding scale with a simple ask. I want every teacher in California, regardless of their school’s financial resources, to have access to Symbiotic Schoolyard. I am on a mission to support California middle school science teachers in restoring biodiversity to their schoolyards as an integrated part of their curriculum.