The EcoGovLab at the University of California, Irvine (UCI) cultivates research, teaching, and diverse collaborations supporting next-generation environmental governance. One important project, ongoing since 2018, is to design and deliver a large, lower-division undergraduate anthropology class—“Environmental Injustice”—which fulfills general education requirements for its focus on multiculturalism in the United States. In this article, we share how we teach this course and why, explaining how “storylining” is part of our approach. We are not suggesting that the course we teach is exceptional—we draw on lessons from many thoughtfully designed courses and educators. Our goal is to open a dialogue about a storyline approach in environmental justice pedagogies, hoping to help create a throughline from kindergarten to college and beyond. Ten Strands’ Climate Change and Environmental Justice Program (CCEJP)—for which we are developing eleventh- and twelfth-grade curricula—opens many generative spaces for this dialogue.

Because UCI’s Environmental Injustice course fulfills a general education requirement, we attract and welcome students from all majors, many without prior interest in environmental issues. A key goal of the course is to call students into roles as environmental activists and professionals. The course is research intensive and offers students opportunities to bring in their own interests and expertise through the collaborative production of case studies focused on environmental injustice in different communities across California. We use a “flipped classroom” approach, where class time is spent on student activities rather than content delivery. By doing so, we want to give students deep experience with and appreciation for collaborative practice as a way to learn, produce knowledge, and take care of the world.

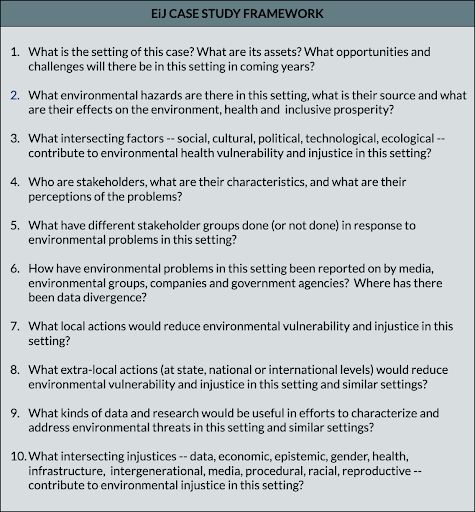

Over the course of a ten-week quarter, groups of roughly ten students produce three case studies of environmental injustice characterizing fast disasters (sudden, explosive hazards), slow disasters (routine pollution), and combo disasters (climate change). This past fall, through a new step we added to the research process, student research groups centered their case studies on a public school in the county they were assigned. In doing their case studies, students learn to identify different environmental hazards (wildfires and hazardous waste facilities, for example), and how different rights holders and stakeholders are taking action to address environmental injustice at both local and extra-local levels. Student research groups are also asked to propose their own priority actions to address environmental injustice in their setting. The case study concludes with an analysis of “intersecting injustices” that combine to produce environmental injustice.

Responding to the ongoing escalation of climate change, chemical pollution, and environmental deregulation, our goal is to educate a new generation of environmental governance researchers. This is not just about teaching students research and advocacy skills—it is about challenging students to reconfigure how they see themselves in the world. Many students come to our class ambivalent or cynical about their ability to effect change. They are paralyzed by the complexity of the issues that they face. Our task is to unsettle these dispositions of individualism, cynicism, and passivity. We cannot do this by telling students what to believe or how to be. Instead, we aim to create pathways that help students redefine themselves as adept and collaborative learners ready to work against environmental injustice. We call these pathways “storylines.”

Our approach builds on and differs from the storyline method developed in Scotland for interdisciplinary environmental education in public schools, the NextGen Storylines, and storywork that centers Indigenous survivance and resurgence. In our teaching, we build storylines that both carry course content and position our students as active agents of environmental change. Our storylining tactics include the following:

- Situating Learners in Cascading Communities of Practice: Environmental injustice and its solutions are complex and daunting. We teach students that they don’t have to figure them out on their own by setting up cascading “communities of practice” for the research and advocacy proposals they develop. In communities of practice, learners enter into dialogue with their peers about what they know, what they don’t know, and what they need to know. We scaffold this in the classroom with research “sketchbooks” that guide learners through data collection and analysis activities to characterize environmental injustices in a particular setting. After completing three environmental injustice case studies guided by a ten-question framework used in all three, most students come away adept at using the framework. Some students come away ready to mobilize the ten-question framework in their own continuing research, often in collaboration with UCI’s EcoGovLab and community partners. This, in turn, opens up possibilities for powerful cascade learning. As students share and help develop the ten-question framework with community partners, they step into roles as teachers themselves, helping community partners build data and analyses that can support their work for environmental justice.

- Working Against Paralysis and Anxiety in Thinking and Action: Two questions in our ten-question environmental injustice case study framework ask students to propose specific actions—at both local and extra-local levels—to improve conditions in the settings they are focused on. Moving between problem characterization and action proposals doesn’t come easily for many students. Being assigned to develop such proposals thus forces their hands—in a way that helps them move beyond the paralysis and anxiety that many students start with. Working with their research group, students do research to understand how a particular problem has been addressed in different places. They then decide which actions would likely be effective in their setting, then develop concrete plans to implement those actions. This reminds students that environmental issues are not intractable and teaches them how to identify actions that are both small enough to be achievable and large enough to make a difference. The very act of completing three environmental injustice case studies also works against students’ paralysis and anxiety. They see themselves and their peers developing knowledge that matters, and in so doing, come to think of themselves as knowledge actors.

- Responsive and Responsible Knowledge: Our course rotates around the ten-question environmental injustice case study framework as a “knowledge integrator”—that makes visible the diverse types of data, interpretation and knowledge needed to characterize and address environmental injustice. In using the case study framework, they learn about “missing data,” different interpretations of the same data, and the importance of data literacy and capacity. They also learn that both qualitative and quantitative data are important; one of the case study questions calls upon them to design a qualitative research project that would draw out important dimensions of environmental injustice in their setting. Importantly, the case study framework both organizes diverse knowledge and shows that there is always more knowledge work to be done. Our aim is to call our students into the work, enlivened by what they have learned and accomplished through our guidance.

Conclusion: Storyline as Pedagogical Strategy

As both teachers and social science researchers, we work to understand where our students are when they join our course and where we can move them through creative pedagogy. It is a double movement for us as educators and for our students. It is in this double movement (and double bind) that our teaching unfolds. Like literary texts and museum exhibits, a class walks students through a series of encounters, drawing them into a storyline. Often, these stories are latent rather than explicit, but they are always there, underlying and structuring students’ experiences and learning outcomes, much like the rhetorical structures that underlie and shape texts. Thinking in terms of storylines is a way to draw these matters of content, form, and design to the surface, so that they can be creatively evaluated and continually refined. It also lays ground for collaborative and theoretically animated reflection on teaching itself.