The modern American schoolyard is dominated by two elements: asphalt (hardscape) and lawn (softscape). The living schoolyard movement, covered in Sharon Danks’s book Asphalt to Ecosystems, transforms schoolyards into lush environments “that strengthen local ecological systems” and provide opportunities for “place-based, hands-on learning.”

While the conversation about living schoolyards has focused on asphalt removal, the transformation of underutilized lawn is an important tool for schools to conserve water, cool campuses, and encourage biodiversity, while expanding holistic and integrated educational opportunities.

Daily Acts’ Climate Resilient Schools Program

Daily Acts (DA) is an environmental education nonprofit based in Petaluma, California, that connects people and builds community through education, action, and policy to address climate change. To demonstrate the effectiveness of schoolyard water conservation projects, DA has partnered with the Land Resilience Partnership to pilot the Climate Resilient Schools Program, a multi-benefit water conservation program to design and install projects at four schools through 2026.

The Land Resilience Partnership (LRP) is a statewide initiative to spread land-based resilience projects by providing design and install support where people live, work, and play. Grant funding from the Bay Area Integrated Regional Management Program, a subsidiary of California’s Department of Water Resources, enables DA and LRP to work with schools in Petaluma’s economically distressed and underrepresented communities.

Three water conservation project-types were identified to improve student schoolyard experiences:

- Lawn conversion to climate-resilient landscapes

- Rainwater catchment and storage tanks

- Rain gardens and bioswales

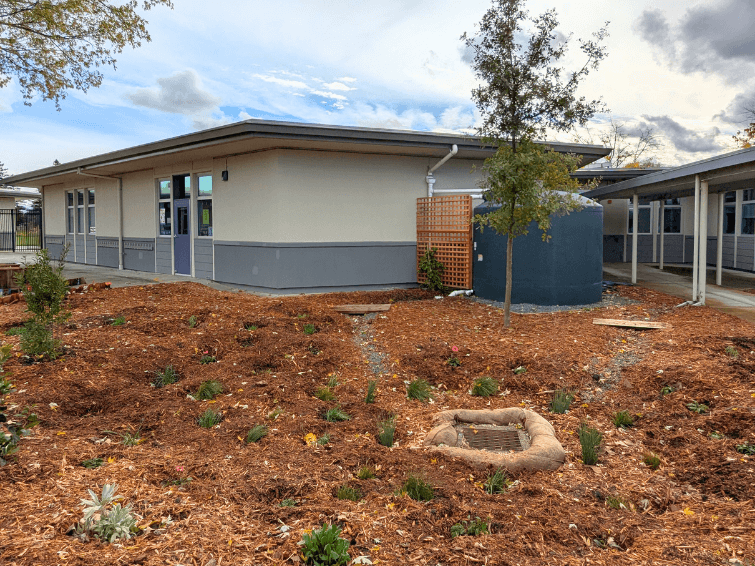

So far, DA’s Climate Resilient Schools project has partnered with two schools to transform 23,000 square feet of irrigated lawns to climate-appropriate gardens through sheet mulching and irrigation conversion. By first converting sprinklers to drip irrigation and then layering compost, cardboard, and mulch (sheet mulching), these lawns were composted in place and prepared for planting drought-tolerant and native plants. Additional water is saved through rainwater harvesting projects like storage tanks and rain gardens that sink water into the landscape.

Emerging Benefits of Schoolyard Transformations

These lawns were not only underutilized and devoid of biodiversity, they were also massive users of water, needing more than 660,000 gallons annually to stay green year round. Once installed, these landscapes use about 85 percent less water, needing 87,000 gallons of annual irrigation. New plants are supported by nutrient-rich rainwater harvested in seven tanks, totaling 23,000 gallons of storage and two rain gardens that sink approximately 4,000 gallons every rainstorm.

Lawn transformation and rainwater harvesting projects at just two schools has helped Petaluma save over half a million gallons of water annually while supporting pollinator and wildlife habitat, providing shade, building soil health, sequestering carbon, enhancing evapotranspiration, recharging groundwater, increasing food access, and filtering stormwater runoff.

In addition to ecological benefits, living schoolyard projects have emergent social, physical, and developmental benefits. According to Bikomeye et al, schoolyards with natural elements enhance physical and socioemotional health by creating shade, varied opportunities for physical activity, and improved mental health.

Furthermore, student exposure to natural systems and native California plants ingrains a sense of place by educating students about our unique Mediterranean climate. These transformations are impactful for students who, according to Wendy Titman, read elements in the schoolyard as a “hidden curriculum” that informs their sense of place, perceived value, and self-identity.

Facilitating Engagement in Living Schoolyards

Sustained community engagement and stewardship is key to successful implementation of living schoolyard projects. Through collaborative project development, community installation events, and curriculum-informed design, students and community members are more likely to feel connected, empowered, and responsible for stewardship.

Collaboration Through Listening Sessions

Community involvement in design through listening and feedback sessions is an iterative process that requires humility, openness, and collaboration. In DA’s most recent project at La Tercera Elementary School, various community engagement sessions solicited input from the following stakeholders:

- Administrators: Project scope was collaboratively and iteratively developed with the principal, superintendent, and maintenance director.

- Teachers: Through presentations at staff meetings and written surveys, teachers helped narrow the project scope, inform designed pathways, and determine gathering areas.

- Parents: Opinions regarding the plant palette and landscape elements were solicited at back-to-school night and via survey.

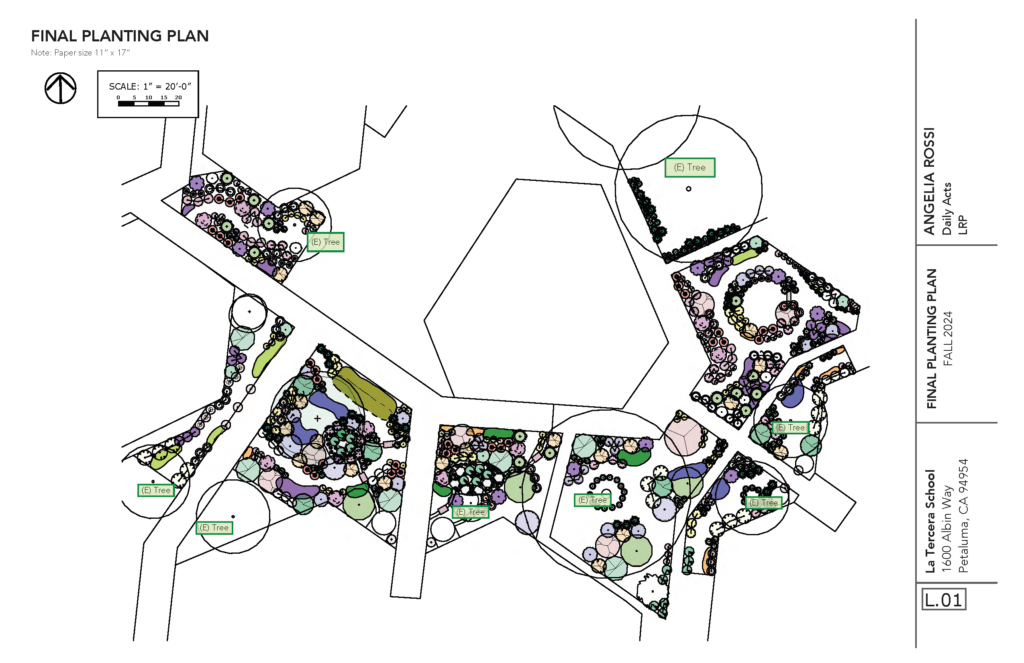

- Students: DA delivered educational presentations to classrooms on the water cycle, water conservation, and changes on campus. During these presentations, students voted for their favorite plants from our native plant palette, influencing the final planting plan.

A Unique Approach to Community Landscape Transformations

DA’s community-centered approach to design and installation facilitates public engagement, connection, and care. Volunteer planting days, supported by local community service partners, bring intergenerational community members together to learn and plant side by side. For other elements of installation, DA works with educators to provide workforce training to future conservation workers through partnership with Conservation Corps North Bay.

The best way to empower student stewards to care for and engage with their landscape is through hands-on involvement. DA hosted two planting days with La Tercera Elementary School to plant fifty-three different species of drought-tolerant and rain garden plants, totalling over eight hundred plants!

The first program was open to volunteers including students, parents, teachers, organizations, and community members. For the second planting day, which involved students only, every student on campus (paired with their big or little buddy) planted and watered-in their plant, from yarrow and grey rush to coffeeberry and valley oak.

Student involvement in installation builds stewardship and leadership. Students who participated in the first planting day showed their peers how to plant during the second planting day. Additionally, students check in on the plant they planted, conveying a sense of ownership, responsibility, and care. Ongoing stewardship and involvement is encouraged by staff that designate class stewards and give school currency to students that pull weeds.

Designing Living Landscapes for Learning and Stewardship

Thoughtful and collaborative landscape design creates educational spaces in otherwise underutilized places. Teacher input to integrate plant design with curriculum and overall themes inspired the final planting plan.

At La Tercera Elementary School, various sections of the landscape highlight different educational and ecological themes:

- The Nest includes a stump circle as an outdoor classroom, intentionally located outside the classroom of a teacher who often takes their students outside to read.

- The Food Forest includes successional layers of edible and medicinal plants with cultural relevance, selected with input from a social studies teacher whose curriculum highlights indigenous cultures and the role of colonization in California history.

- The Beaver Basin is the site of a rain tank and rain garden planted with riparian plants. Between the Beaver Basin and Nest is a wood edge of student art, a project spearheaded by their makerspace and science teacher.

- The Sensory Spiral was designed by grouping plants based on their blooming color, texture, and smell, with a special spot for plants with animal names.

By integrating educational elements and existing curriculum in design, it is even more likely the landscape will be cared for in perpetuity by teachers and students.

Schoolyard ecology projects like lawn conversion to low-water gardens and rainwater harvesting transform the “hidden curriculum” of schoolyards. By not only teaching about ecology but demonstrating restoration, schoolyards communicate a “culture of care.” Starting with their school grounds, schools must plant seeds of change by inspiring students to appreciate the beauty of nature and become stewards of their environment.

Daily Acts is a holistic environmental education nonprofit that takes a heart-centered approach to inspire transformative actions that create connected, equitable, and climate-resilient communities. Be sure to check out their website for further case studies and educational resources to take action today.

7 Responses

WOW!

Great job!

We have a local group called the Temecula Valley Native Plant Network.

We operate mainly on Facebook and Instagram, and through email.

We promote workshops, field trips, and local projects.

One of our project categories is working with local schools.

This article is truly inspiring.

THANK YOU!

Hi Margaret,

Thank you for your lovely feedback. It is great to learn more about the Temecula Valley Native Plant Network and the work you are doing with local schools.

There are so many wonderful approaches to integrating education and ecology; field trips and workshops are certainly powerful, I remember how inspired I was as a child whenever we went to learn in the field!

As a former elementary school teacher, I like the way you are bringing environmental justice into the curriculum and involving the students in the planting and care of the plants.

Thank you, Morgan, et al.

Hi June,

Lovely to hear from you and I really appreciate your perspective. I didn’t know you were an elementary school teacher. I hope to cross paths with you again soon!

Fantastic and Wonder~Full! Morgan, your information is exactly what California and this planet needs to learn Pronto! Thank you! Keep on groovin❤️🌴

This work is so inspiring! I work with kids in many capacities and love to see what other members of the community are doing to engage students in active learning. Thank you for sharing, Morgan!

It’s so cool to see and read about people making a change and also inspiring others!

We need the new generations to be close to nature and to understand how important it is to respect it and nurture it and you are helping them get there!!

You are so cooool <3