Learning is a life-long activity, and we want to instill that drive in all students. If you can engage students by making learning relevant and fun—as environment-based learning does—then they will not only perform better in school, but they will want to become learners for their whole life. In thinking about this holiday season, I was wishing to be in the classroom again so I could highlight environmental connections through the season’s many traditions across cultures (much like the EEI Curriculum does across core subjects). Different traditions have evolved from listening and responding to particular environments, and they all have unifying threads that weave them together.

Here in the northern hemisphere the winter solstice is near. It’s a time when people observe a wide variety of customs and traditions—religious, spiritual, cultural, and social. And although the names and details vary they are all linked together by the natural world!

Let’s take a trip around the globe and look at the common threads weaving us together in this season as we anticipate the return of longer, sunnier days:

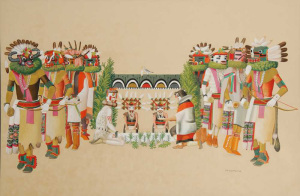

Soyalangwul is the winter ceremony of “The Peaceful Ones,” also known as the Hopi Indians. The Soyal ceremony brings the sun back from its long winter slumber. It also marks the beginning of another cycle of the Wheel of the Year, and is a time for reflection and purification. Pahos (prayer sticks) are made prior to the Soyal ceremony to bless all the community, including people’s homes, animals, and plants. The kivas (sacred underground ritual chambers) are ritually opened to mark the beginning of the Kachina season (the time when rain and fertility returns to the land). The Kachinas, spirits that guard over the Hopi, dance at the winter solstice Soyal Ceremony and may even bring gifts to the children. At Soyal time elders pass down stories to children, teaching pivotal lessons like respecting others.

Soyalangwul is the winter ceremony of “The Peaceful Ones,” also known as the Hopi Indians. The Soyal ceremony brings the sun back from its long winter slumber. It also marks the beginning of another cycle of the Wheel of the Year, and is a time for reflection and purification. Pahos (prayer sticks) are made prior to the Soyal ceremony to bless all the community, including people’s homes, animals, and plants. The kivas (sacred underground ritual chambers) are ritually opened to mark the beginning of the Kachina season (the time when rain and fertility returns to the land). The Kachinas, spirits that guard over the Hopi, dance at the winter solstice Soyal Ceremony and may even bring gifts to the children. At Soyal time elders pass down stories to children, teaching pivotal lessons like respecting others.

Dōngzhì Festival (The Extreme of Winter) is one of the most important festivals celebrated by Chinese an d other East Asian people when sunshine is weakest and daylight shortest. The origins of this festival can be traced back to the yin and yang philosophy of balance and harmony in the cosmos. After this celebration, there will be days with longer daylight hours and therefore an increase in positive energy flowing into the people and the land. It is a time for extended family to get together at ancestral temples if possible, and share in traditional foods. One activity that occurs during these get-togethers (especially in the southern parts of China and in Chinese communities overseas) is the making and eating of tangyuan (balls of glutinous rice) that symbolize reunion and are usually brightly colored.

d other East Asian people when sunshine is weakest and daylight shortest. The origins of this festival can be traced back to the yin and yang philosophy of balance and harmony in the cosmos. After this celebration, there will be days with longer daylight hours and therefore an increase in positive energy flowing into the people and the land. It is a time for extended family to get together at ancestral temples if possible, and share in traditional foods. One activity that occurs during these get-togethers (especially in the southern parts of China and in Chinese communities overseas) is the making and eating of tangyuan (balls of glutinous rice) that symbolize reunion and are usually brightly colored.

Šab-e Čella or Yalda, is an Iranian festival celebrated on the “longest and darkest night of the year,” the night of the Northern Hemisphere’s winter solstice. It’s a time when friends and family gather together to eat, drink and read poetry until well after midnight. Fruits and nuts are eaten and pomegranates and watermelons are particularly significant. The red color in these fruits symbolizes the crimson hues of dawn and glow of life. Decorating and lighting the house and yard with candles is also part of the tradition.

Christmas or Christ’s Mass is one of the most popular Christian celebrations as well as one of the most globally recognized midwinter celebrations. The birth of Christ is observed on December 25, which was the winter solstice upon establishment of the Julian calendar. Universal activities include gathering with family and friends, decorating trees, lighting up homes, feasting, midnight masses, good deeds, and gift giving in the tradition of St. Nicholas.

Yule or Jul (Northern Europe, Scandinavian, Norse and Germanic) was to be celebrated on the night leading into December 25, to align it with the Christian celebrations. Yule logs were lit to honor Thor, the god of thunder. Feasting would continue until the log burned out, three or as many as twelve days. Early Germans considered the Norse goddess, Hertha or Bertha to be the goddess of light, domesticity and the home.

People baked yeast cakes shaped like shoes, which were called Hertha’s slippers, and filled with gifts. During the Winter Solstice houses were decked with fir and evergreens to welcome her coming.

Reflecting, feasting, family, and honoring the cycles of nature—our connections with one another and our environment are what flows around us at this time of the year.

Since we’re looking around us and noticing our environment, let’s not overlook our friends from the Plant Kingdom, whose presence is especially noticeable in how Americans celebrate:

The Christmas Tree: The evergreen tree  symbolized immortality—Germanic people would bring evergreen boughs into their homes during winter to ensure the protection of the home and the return of life to the snow-covered forest. The first record of a Christmas tree is in Strasburg, Germany in 1604. German immigrants and Hessian soldiers hired by the British to fight the colonists during the American Revolution brought the Christmas tree tradition to the United States.

symbolized immortality—Germanic people would bring evergreen boughs into their homes during winter to ensure the protection of the home and the return of life to the snow-covered forest. The first record of a Christmas tree is in Strasburg, Germany in 1604. German immigrants and Hessian soldiers hired by the British to fight the colonists during the American Revolution brought the Christmas tree tradition to the United States.

Mistletoe: Traditions involving mistletoe date back to ancient times. Druids believed that mistletoe could bestow health and good luck. Welsh farmers associated mistletoe with fertility—a good mistletoe crop foretold a good crop the following season. Mistletoe was also thought to influence human fertility and also played a role in a superstition concerning marriage—it was believed that kissing under the mistletoe increased the possibility of marriage in the upcoming year!

Holly was considered sacred by the ancient Romans. Holly was used to honor Saturn, god of agriculture, during their Saturnalia festival held during the winter solstice. The Romans gave one another holly wreaths, carried it in processions, and decked images of Saturn with it. During the early years of the Christian religion in Rome, many Christians continued to deck their homes with holly to avoid detection and persecution by Roman authorities. Gradually, holly became a symbol of Christmas as Christianity became the dominant religion of the empire.

Holly was considered sacred by the ancient Romans. Holly was used to honor Saturn, god of agriculture, during their Saturnalia festival held during the winter solstice. The Romans gave one another holly wreaths, carried it in processions, and decked images of Saturn with it. During the early years of the Christian religion in Rome, many Christians continued to deck their homes with holly to avoid detection and persecution by Roman authorities. Gradually, holly became a symbol of Christmas as Christianity became the dominant religion of the empire.

Wassailing is the tradition of going from house to house caroling, eating, drinking, and socializing with friends and relatives. Wassailing, however, was originally an important part of a horticultural ritual! In England, it focused on the apple orchards. The purpose was to salute the trees in the dead of winter to insure a good crop for the coming year. The wassail procession visited the principal orchards of the area, caroling as it went. In each orchard, major trees were selected and cider or liquor was sprinkled over their root systems. The care with which the ceremony had been executed was measured by the crop yield the following year.

Culture, tradition, season, time and environment—they all weave together at this special time of year, in so many shared threads. We at Ten Strands would like to salute all of our friends and allies—human, vegetable, animal, and mineral—this holiday season, and offer our thanks and gratitude. The support we have received this year has been far beyond what we expected, and we are so deeply appreciative. We look forward to moving into 2015 in our healthy, hearty, and hale state, ready to find new and creative ways to engage students about learning with the added benefit of an environmental lens on the world around all of us.

A very happy holiday season to you all, and wishing you a healthy new year!

2 Responses

Nice synopsis, Will. I am celebrating solstice with ten hours of daylight in the desert instead of five in Haines. A nice change. I hope your holiday celebrates itself with family connection, hearty warmth and plenty of Joy for all.

Where is this celebration from originally?