This article was written by Dr. Shelley Brooks in collaboration with Candice Dickens-Russell, Jose Flores, Nate Ivy, and Mary Walls.

“Social studies is essential to understanding and addressing our environmental challenges. We usually think of science as the lens for learning about the environment, but without geography, economics, civics, psychology, anthropology, history, and sociology, we can’t fully understand humankind’s decisions about how to use and preserve natural resources.” – Nate Ivy

In what must be gratifying for many civics teachers across the country, students are using their knowledge of the U.S. governing system to work for change in gun control laws. This student movement is the most recent in a long history of challenges to the status quo. From the student sit-ins and voter registration drives of the Civil Rights Movement, to the Chicano student walkouts to demand culturally-relevant and equitable education, to widespread student participation in the first Earth Day in 1970, earlier generations of student activists, like those today, engaged in matters important to their lives, the lives of their peers, and their future.

As a group of educators committed to building student knowledge and empowerment, we organized a panel on cultivating environmental literacy at the California Council for the Social Studies 2018 Conference in San Diego at the end of March (we appreciate Ten Strands making this possible!). Our goal for this conference was to share with other educators how we see environmental literacy as a tool for students to improve their discipline-specific content knowledge while also learning how to promote justice and equality by supporting a healthier, more sustainable environment for all.

We were excited to discuss a number of resources with the panel audience that we are sharing here:

Nate Ivy, a member of the Environmental Literacy Task Force and civics teacher in Fremont Unified School District, discussed compelling classroom activities that help link students’ daily lives and possessions to the required natural resources. He also highlighted a valuable classroom tool, CalEPA’s EnviroScreen, which can be used to motivate students’ civic-minded inquiry into the health impacts of various environmental conditions across the state.

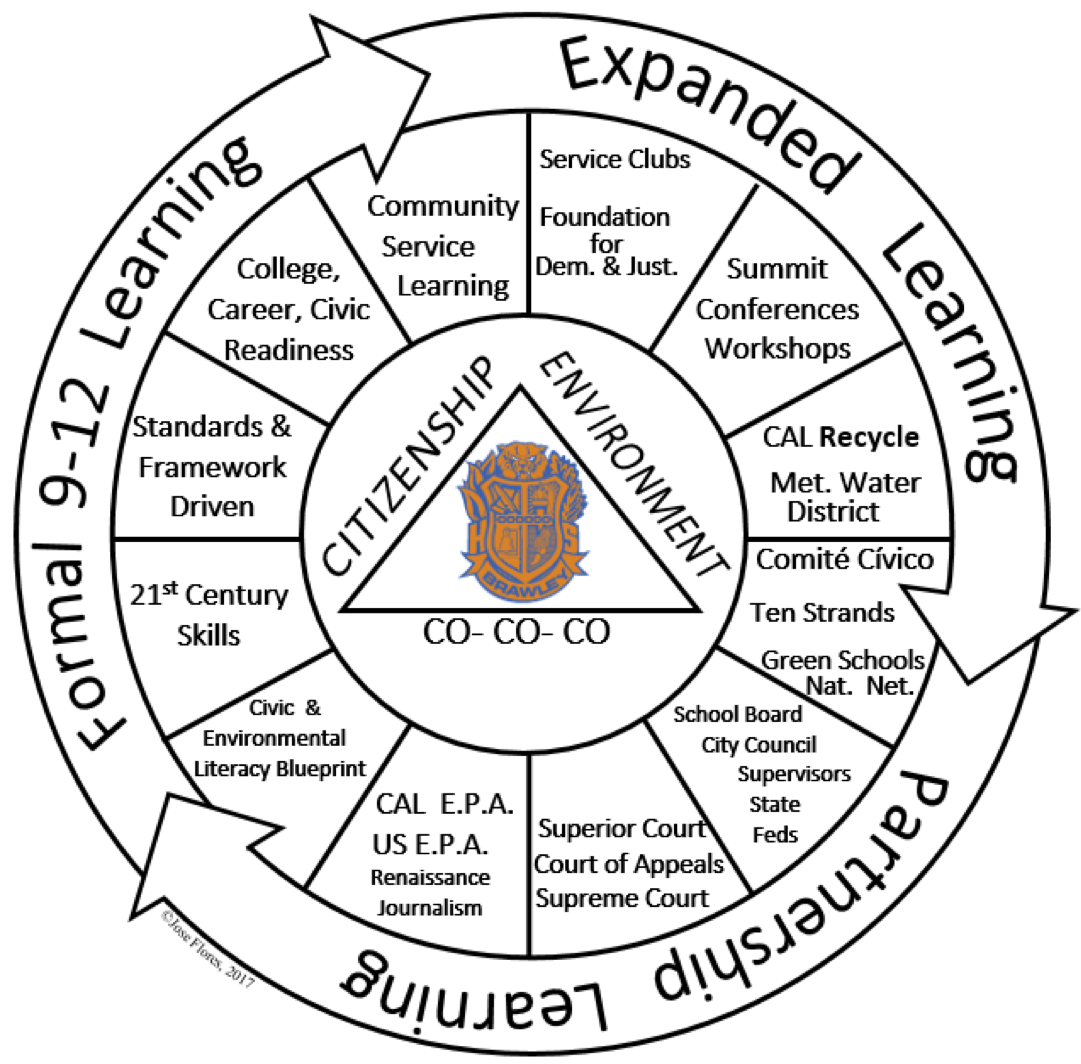

Jose Flores, a U.S. history and civics teacher at Brawley Union High School, member of the Environmental Literacy Steering Committee (ELSC) and of California’s Instructional Quality Commission, shared with the audience examples of how he engages his students with their local community and with the greater world around them, including attending city council meetings, advocating for legislation that will address their needs and their future, and participation in conferences and summits relevant to their lives. Jose focuses on bridging the opportunity gap through these various formal and informal educational experiences by promoting student leadership, voice, and public speaking.

Mary Walls, Coordinator for Region 10 of the California Regional Environmental Education Community (CREEC) Network and proponent of action-driven inquiry, shared how she approaches education as a means for creating in students the desire to better themselves, their communities, and their world. This action driven inquiry model works through a cycle of learning and questioning to increase students’ capacity to act on matters of importance.

Candice Dickens-Russell, Region 11 CREEC Coordinator, Director of Environmental Education at TreePeople, and member of the ELSC, explained how TreePeople builds students’ knowledge of and engagement with their communities through the lens of the environment and shared how local CREEC resources can assist teachers in connecting with organizations like TreePeople in their own regions. She linked environmental literacy to environmental service learning—how it prioritizes the youth voice and works with young people to identify community needs and evaluate program outcomes. TreePeople’s Youth Leadership Program invites students to direct their projects from the beginning to the end.

Shelley Brooks, academic coordinator for the California History–Social Science Project and member of the ELSC, shared links to current events-based teaching resources that help situate developments in the news – such as student activism, Cape Town’s water crisis, and debates over Bears Ears National Monument and the management of public lands – in their historical context. These resources are intended to give students the knowledge, the vocabulary, and the perspective to act as informed members of society.

An oft-repeated phrase, “students are our future,” is a constant reminder of why it is so important that through education students develop the knowledge, skills, tools, and motivation to engage with their world in ways that promote justice and the well-being of all people and the planet.