When an estimated 400,000 middle school students across the state of California participate in the upcoming seventh-grade Climate Change and Environmental Justice Program (CCEJP) curriculum from Ten Strands, they will be a part of a one-of-a-kind experience designed by their peers across the state and around the world.

When Ten Strands announced its search for partners to create the new curriculum, the international nonprofit Global Nomads Group saw an opportunity to apply its youth-driven curriculum design model to a new classroom need. Given that Global Nomads Group previously created online courses related to human rights and ocean health, the new topics fit neatly with its social and environmental justice-oriented mission.

But it was the Ten Strands requirements for an inquiry-based approach to address specific questions from students that convinced Global Nomads Group it had something special to offer.

“Even in a student-centered design process, typically, students are not involved until late-stage feedback,” said Katie Cox, program manager at Global Nomads Group. By contrast, the organization’s unique Content Creation Lab (CCL) system turns this traditional curriculum development model on its head. Instead of simply having young people offer feedback on content that adults have already created, youth designers create the curriculum itself from the very beginning.

By involving a diverse group of youth participants—from across California and around the world—Global Nomads Group is designing a curriculum that is familiar, relevant and both placed-based as well as situated within a global context. The result is that Ten Strands will soon offer California’s middle school students a unique unit by youth and for youth, designed to be accessible to the widest range of students and abilities.

By Youth, for Youth

In the CCL, teams of youth interns from around the world, working with guidance from adult mentors and subject matter experts, develop curriculum that is original, relevant, age appropriate, and tied to recognized educational standards. In recent years, CCL teams have created numerous online courses in the Student to World program on topics as varied as mental health, women’s rights, and overcoming bias.

In order to meet the unique requirements set forth by Ten Strands, Global Nomads Group assembled a cohort of thirty-three interns, ages twelve to twenty-two, to participate in the new session. Half are from California, and the other half are from sixteen additional countries around the world. The program staff deliberately recruited a diverse group of participants, including from underrepresented or marginalized communities and backgrounds, and prioritized a variety of lived experiences over traditional academic achievements.

“When we’re recruiting for diversity among our youth designers,” said Sandra Stein, chief of programs & learning at Global Nomads Group, “it’s because we need that diversity in order to make a curricular product that will work for the diverse learners that it’s intended for.”

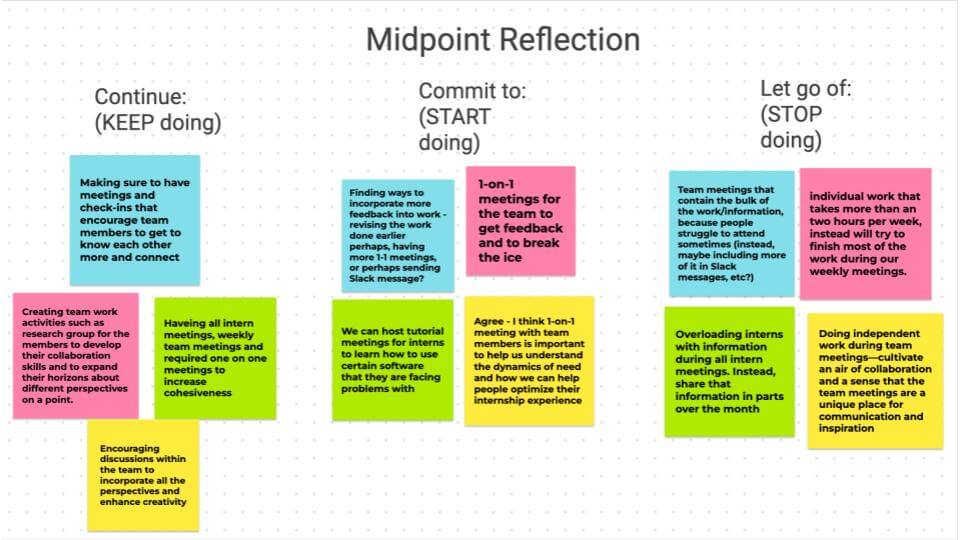

Some of the interns served as team leaders and began in October 2022 to create the organization’s protocols and learn how to support their peers who joined two months later. The youth teams manage their own processes, scheduling Zoom calls across numerous time zones, and create their own online workflows to manage the complex work of creating a combined text and video curriculum.

“Beforehand, I thought that teachers just knew everything they needed for the curriculum,” one youth intern said, “but I’m finding that I am learning new things after each meeting and on average doing more research than I would as a student.”

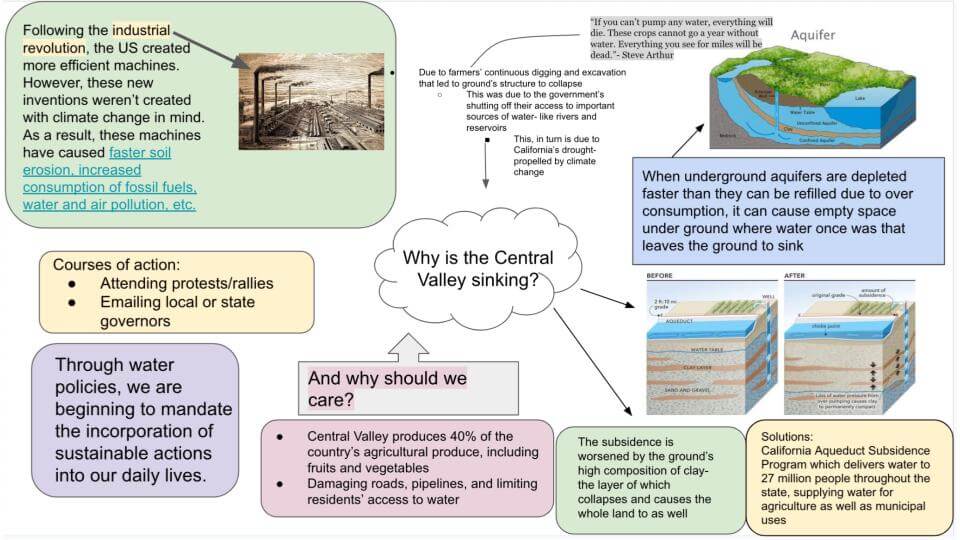

After reviewing the Ten Strands requirements, the interns developed several original ideas for how to represent the effects of climate change in the state before choosing an area of focus: a virtual field trip of a town in California’s Central Valley to study land subsidence (i.e., sinking) caused by colonization, industrial agriculture, drought, and climate change. The story follows a series of protagonists so learners can explore causes and impacts of climate change not always told in common narratives.

Khadija, a sixteen-year-old intern from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, said, “Usually, as a student, I ask myself often about why we’re learning something. As a content creator, I know every aspect of the journey, and I know the real-life consequences of the information we’re including in the curriculum.”

One team’s draft explanatory model for land subsidence in the Central Valley, created March 2023 by Team Cloud (Ifeanyi, Khahdija, Katinka, Maya, Sarah, Sophia, and Vivian).

Diverse Students and Diverse Perspectives

A key part of the learning process involves understanding climate change and environmental justice not only using Western modes of inquiry but also through Indigenous ways of knowing, like knowledge traditions of the native communities that have inhabited California for thousands of years. This includes place-based inquiry examining traditional land and water stewardship, tribal sovereignty, and social and environmental justice.

“When we talk about valuing Indigenous knowledge in environmental education,” said Cox, “we are in part talking about grounding environmental learning in place and in history.”

The diverse pool of youth participants contributes to this perspective shift. While half the CCL interns are California residents, the inclusion of youth participants from sixteen additional countries—all affected in different ways by climate change—means they can collectively draw connections that remind curriculum participants that the climate and environmental justice movements are global phenomena.

“They bring experiences from different parts of the world that highlight how the climate justice implications in what we’re seeing in California are not entirely unique to California,” Stein said.

By examining climate change through a range of both Western and non-Western lenses, the CCL participants are designing a curriculum that speaks to a wider range of California’s inhabitants, including many who are often overlooked in mainstream discussions of climate change.

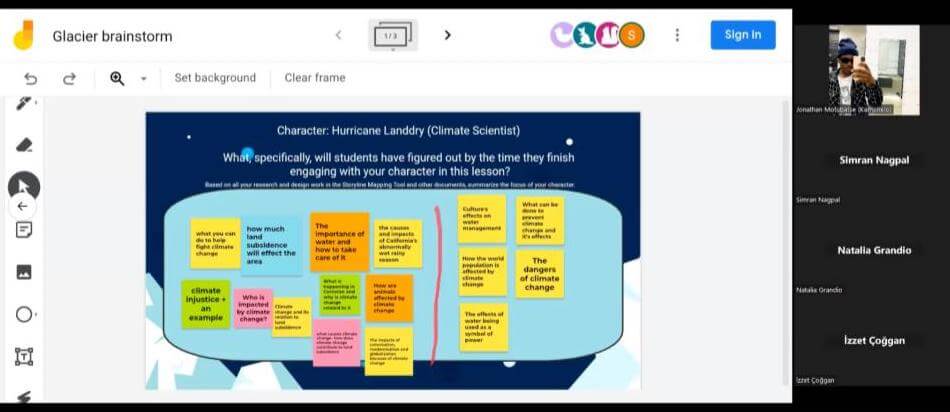

Team Glacier (Abigail, Fatima-Zahrae, Izzet, Jonathan, Joy, Natalia, and Simran) brainstorm the focus for the climate scientist character during a recent team meeting.

Reaching Every Learner

The CCL is designed to center the perspectives of youth who are often marginalized in traditional learning environments that are not designed for diversity. “In a lot of our schooling experiences, we’re trained—explicitly or implicitly—to pretend we understand, and ‘fake it ’til we make it’ and go along,” Cox said. “It leaves behind a lot of people who learn in ways that aren’t being served by a traditional lesson plan or a traditional classroom environment. In the CCL, we encourage and reward asking questions and working together to bring everyone along.”

The CCL incorporates the principles of Universal Design and includes participants with a range of perspectives, experiences, and abilities. The cohort works from the same inclusive practices (accessibility and inclusion) documents that the Global Nomads Group staff use.

Stein and Cox credit making Universal Design a core part of the process—and by centering those learners who are often marginalized by typical classroom experiences—with making the CCL better able to produce curricula that resonate with a wider spectrum of California students.

“In coming up with ideas that are compelling and exciting for them,” Cox said, “this incredibly diverse group of youth designers ensure it’s curriculum that’s really compelling and exciting and accessible for the really diverse group of learners that they are designing for.”

In this jamboard, youth team leaders reflect on their own leadership practices and brainstorm ideas about what to continue, commit to, and let go of in the second half of the internship (created March 2023 by Citlalli, Efsa, Jonathan, Katinka, Nour, Rainy, Simran, and Sophia).

A Curriculum for All Students

The CCL process of creating content offers insightful experiences that promise to improve the learning experience for the eventual learners who utilize the Ten Strands curriculum. In addition to the youth involvement, global perspective, and Universal Design principles, the welcoming, supportive environment of open inquiry can yield surprising results.

For example, encouraging hesitant youth participants to ask questions—even seemingly obvious ones—often surfaces overlooked or unaddressed sources of potential confusion among learners. By addressing these during the content creation process, the group is able to produce a curriculum that is clearer and more accessible to a wide range of learners.

The process, Cox said, is one of “reframing ‘not knowing’ as a really valuable form of knowledge.”

The goal of Global Nomads Group’s participation in Ten Strands’ Climate Change and Environmental Justice Program is to help Ten Strands offer a curriculum that is as relevant and engaging for the eventual learners as it has been for the youth creators.

As intern Khadija said, “I enjoy having control over the information given and hope other students will enjoy it as much as I enjoyed making the curriculum.”