I was in class three times last week learning about land and water. The first was Laura Honda’s 4th grade class at Manor Elementary School in Fairfax, California. Laura is a Teacher Ambassador for the Education and Environment Initiative Curriculum (EEI) and uses the EEI extensively with her students. Laura was teaching Lesson 5 from the 4th grade Life and Death of Decomposers unit. Her students were learning that human food production ultimately depends on decomposers’ abilities to replenish nutrients in topsoil, making it more suitable for agriculture. She started the class by reflecting on a previous lesson to make sure her students had grasped earlier concepts and vocabulary—producers, decomposers, scavengers, etc. She then introduced new vocabulary for the lesson—agriculture, humus, and topsoil. Everyone agreed hummus was delicious and should not be confused with humus!

Laura then took an apple and cut it into quarters. She asked students what the first three quarters represented—oceans. She then took the remaining quarter and asked students what it represented—land. Laura then cut the land quarter in half and told students one half of it was not suitable for humans and did they know why? A dozen hands shot up and with them the answers—the Arctic, the Antarctic, large deserts, swamps. There was one eighth left and that too was cut into quarters. The first of the three quarters were discarded because they represented mountains and hills (the land too steep to grow food), cities, houses and roads (no room to grow food), and soil too rocky to grow food.

The last piece of the apple, representing 1/32 of the land, was all that was left to grow food for everyone on the planet. Laura carefully peeled the skin on the last piece and asked her students what they thought it represented? After some discussion everyone agreed it was precious topsoil and that it was very important to take care of it. Later that day Laura’s students had “garden time” where they would be exploring the concepts they learned about soil in the school garden. At the end of the lesson Laura asked her students to write a sentence or two to illustrate the importance of decomposers to topsoil quality. The first student to read his out said, “We depend on decomposition to build good healthy soil to create food.” You can’t argue with that. The lesson ended with a song written by the Banana Slug String Band. The students voted for their favorite song, choosing between Decomposition and Dirt Made My Lunch. Decomposition won this time and the song was in my head for the rest of the afternoon—munch, munch, munch…

Next stop was Walden West Outdoor School in Santa Clara County. Walden West provides environmental science education for 5th and 6th graders in a residential camp setting. Visiting schools come for 4-5 day programs where students explore an outdoor classroom with experienced naturalists and stay in cabins overnight. They focus on teaching state science standards through hands-on learning while exposing students to new social settings, getting them outside, and providing them with new experiences. Students leave the program with a new sense of personal responsibility, independence and understanding of the natural world around them. Walden West has 17 full-time naturalists who work with about 150 students each week.

I was there with Laura Powell, another EEI Teacher Ambassador and CREEC Coordinator. Laura was invited to introduce the EEI to a group of educators being trained as facilitators for Project Learning Tree (PLT). PLT was founded in 1973 and is a program of the American Forest Foundation. PLT uses forests as a window on the world and provides educators (formal and nonformal) with project-based environmental education resources that can be integrated into lesson plans for all grades and subject areas. Over the years, PLT has trained over 600,000 educators. Laura and I were only there for the first afternoon, but we had the opportunity to share the EEIC units that correlate well to PLT’s activities. We also joined the class on a hike in the woods with one of Walden West’s naturalists, Pelican. Pelican treated us like 5th and 6th graders, which, in my case, was just as well. We met in a ring of redwoods and spent the hike identifying trees and looking for wildlife. We saw banana slugs, wild turkeys and California newts. I didn’t get a chance to see any of the PLT activities in action because Laura and I had to leave for our next workshop.

Early Saturday morning we were in Carmichael, California for a day-long Project WET workshop at the Effie Yeaw Nature Center, a 100-acre nature preserve of interpretative trails through riparian woodlands and along the American River. After two days of studying land and trees the focus of the day was on water, using Project WET’s Curriculum and Activity Guide. Project WET was founded in 1984 and is currently active in more than 50 countries. It has been translated into several languages, including Arabic, French, Japanese, Chinese, Portuguese and Spanish.

Once again I was a student, and spent six hours being trained alongside educators from the local area on how to integrate water-based, hands-on activities into classroom instruction. We did six activities during the day—all were paced really well for the classroom and were fun and informative. We started off by estimating what percentage of the planet was water (I naturally knew the answer from Laura Honda’s 4th grade apple activity but decided to keep my insider knowledge to myself!). The activity was to take an inflatable globe and as each person threw it to the next person we collected data on where your right thumb landed–either water or land. After 30 throws we calculated that 70% of the plant was water and 30% was land—not a bad result considering the correct answer is 71% water and 29% land.

The next two activities were The Incredible Journey: Language, Math, and Science in the Water Cycle, and A Drop in the Bucket: Mathematics of World Water Supply. About half the workshop participants were elementary school teachers, and the balance middle and high. Every activity was modifiable for different grades. My favorite activities were in the afternoon because we were outside (proving that I really had taken on the role of student completely). For the first, Blue River: Creating and Interpreting Stream Flow Data, we created a human river (with a main stem and two tributaries) and water flowed along it at different rates—represented by blue beads being handed from person to person—depending on the season. During spring the person upstream from me, who stood at the point where the two tributaries met the stem, couldn’t keep up with the flow and blue beads were flying everywhere and landing on the flood plain. I was the mouth of the river, waiting to release the water into the ocean. We then calculated the rate of flow in cubic feet per second at different times of year. This was all a build up to us walking a trail to the American River to test the health of the water using USGS test kits.

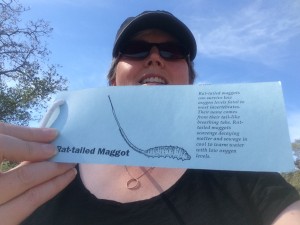

Before getting to the river we played the Macro Invertebrate Mayhem Game where we each got to be a different macro invertebrate, and based on our assignment we displayed certain characteristics that were vulnerable by different degrees depending on exposure to environmental stressors. In the first game I was a mayfly nymph, and didn’t fare too well as the environmental stressor was introduced. In the second I was a rat-tailed maggot, and survived the game to the end to enjoy my life in a stinking river. I had fun being a tolerant organism but I wasn’t left with many friends! All those delicate mayfly and stonefly nymphs were long gone.

So it’s back to the office this week coming up. It is so valuable to spend time in the field talking to teachers who are actually implementing the instructional materials we support and getting feedback from them. Laura’s day-to-day classroom use of the EEI, including the hands-on activities and teacher demonstrations, really helps her students understand big environmental issues and the impact of humans on natural systems. It’s so critical as well to get outside with students and have them experience and interact with nature first-hand. Laura’s onsite garden is perfect for this. My experience at Walden West with the naturalists and my exposure to the fantastic minds-on and hands-on supplemental activities in Project WET demonstrate beautifully the value of lesson extensions that take students outside. I won’t forget what I learned in the field any time soon!

Many thanks to Laura Honda and her students, Laura Powell, Walden West, Project Learning Tree, Project WET, and Linda Desai (the wonderful Project WET presenter for the workshop) for letting me visit and play.

One Response

Can I go with you next time? You made your experience come alive! Thanks, Karen.

Will