On October 17, 2019, over 100 educators from across California gathered to kick off the annual California Association of Science Educators (CASE) California Science Education Conference in San Jose with the Climate Summit Pre-Conference Day. This event was brought back by popular demand after being first held at the 2018 CASE conference in Pasadena. As in 2018, Ten Strands and the California Environmental Literacy Initiative were among the sponsors of the 2019 summit, which allowed educators to attend the pre-conference event for free.

During the pre-conference day, the participating educators had a unique opportunity to strengthen their climate change content knowledge by hearing directly from university scholars. The educators also learned how to teach students about climate change from organizations such as the Exploratorium, Monterey Bay Aquarium, and California Academy of Sciences. But what stood out most from the presentations and subsequent discussions was everyone’s commitment to climate change education as a vital means of fostering students’ environmental literacy. The pre-conference day allowed everyone to do more than just understand the science behind climate change—it was a call to action.

As CASE’s four-year college director and a faculty member at Sonoma State University, I had the pleasure of helping organize the pre-conference day. I am a science education researcher and educator, but I confess that my own knowledge of climate change, and resources for teaching about it, are limited. I saw the pre-conference day as an opportunity to be educated so that I can support my own preservice science teachers in learning how to integrate climate change education, regardless of their discipline. While planning, I read through countless webpages and CVs of scholars in Northern California universities to find those individuals who could engage educators in innovative and timely climate change research. This planning in itself was eye-opening. I did not realize just how many faculty members are engaged in climate change research, even at my own university! I was also amazed at how many organizations have developed Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)-aligned curriculum to support the teaching of climate change. Given that a good cross-section of the scholars, educators, and organizations I learned about would be involved with the pre-conference day, it promised to be an impactful event.

At the start of the day, Ten Strands CEO Karen Cowe and Biomimicry Institute executive director Beth Rattner set the stage by clarifying what we mean by environmental literacy and describing its intersection with California’s Science, History–Social Science, and Health Education Frameworks, namely the focus on student inquiry and student action. Beth followed by demonstrating how educators can engage students in biomimicry design challenges to foster environmental literacy.

Beth also shared various nature-inspired technologies and the winning design from the 2019 Biomimicry Youth Design Challenge, a passive control system for tidal kite electricity generation, inspired by wing designs in nature. I was personally inspired by how students were understanding core science ideas and engaging in science and engineering practices in authentic and meaningful ways in order to actually address climate change issues. Student inquiry and student action were happening—just as proposed by Karen in her presentation.

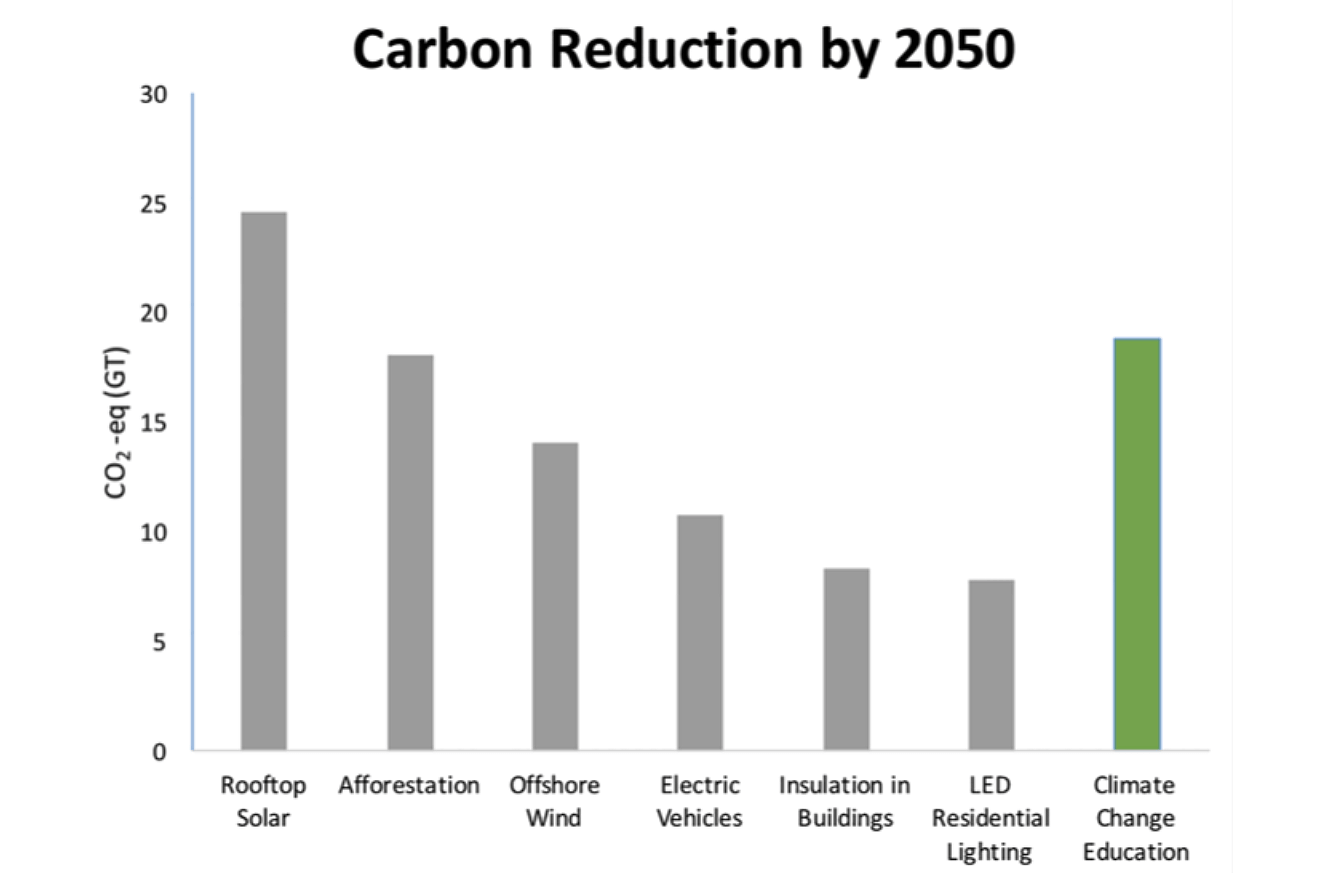

Next, three climate change scholars delved into cutting-edge research that is examining the causes and potential solutions for climate change. First, Dr. Eugene Cordero from San José State University presented “Quantifying How Humans Contribute to and Solve the Climate Crisis.” His presentation helped us understand what contributes and does not contribute to changes in the climate and what steps individuals can do in their own homes to reduce their carbon footprint. He also discussed how his education research organization, Green Ninja, has developed NGSS-aligned curricula to teach students about climate change. In a recent publication, Dr. Cordero has even quantified the impact of climate change education on carbon emissions.

Dr. Isabel Montañez from the University of California, Davis, helped us think about climate change throughout the last 100 million years in her presentation “What Causes Climate Change and How We Know About Earth’s Climate History.” Dr. Craig Clements, also from San José State presented on his team’s research to understand extreme wildfire behavior. His presentation was particularly timely given the devastation of recent wildfires across California, including in Sonoma, Napa, Lake, and Butte counties.

In the afternoon, we switched gears and rotated through a series of round tables in which organizations such as San Mateo County Office of Education, Climate Literacy & Energy Awareness Network (CLEAN), California Academy of Sciences, Monterey Bay Aquarium, Exploratorium, EcoRise, World Savvy, and Energize Schools shared NGSS-aligned curriculum resources that support student understanding of climate change. I was particularly proud that one of my own preservice teachers, Sarah Wickersham, shared educational resources from Sonoma Water and Sonoma Clean Power. In addition, Stephanie Sanchez from Vista Unified School District shared the curriculum she had developed as part of last year’s climate summit cadre. The day concluded with a presentation by Dr. Noah Diffenbaugh of Stanford University, “Is This Global Warming?” Like many others at the summit, I took away an array of ideas that I was excited to share with my pre-service teachers.

Throughout the day I took stock of what I had learned. At the end of the summit I made a few final remarks to the participating educators about how climate change education is a prime example of the vision for high-quality science education: students explaining phenomena and solving problems through experiences that carefully interweave core ideas, science and engineering practices, and cross-cutting concepts.

More importantly, studying climate change in this context is about students realizing their connection to the environment and to one another—locally and globally—so that they can undertake our world’s challenges and have the knowledge and skills to act.

The pre-conference day was just the start of the 2019 climate summit and another amazing CASE conference. The CASE conference opening and closing keynote speakers and five focus speakers all spoke about topics related to climate change. And our seven cadre teams of teachers and scientists encored their 2018 short-course presentations of their learning sequences designed for NGSS. (Read about their work here and access the learning sequences here.) My own preservice teachers who attended the conference noted how presentations related to climate change were the most impactful for them. The conference’s commitment to climate-change education would not be possible without the dedicated conference committee members, executive director, staff, and board of directors, in particular Jill Grace, past president of CASE. I now have my own call to action: to integrate climate-change education and California’s Environmental Principles and Concepts into my course to prepare new science teachers.