Ten Strands launched the San Mateo Environmental Learning Collaborative in 2015 in partnership with the San Mateo County Office of Education. This article is from one of the instructional coaches at the 2019 summer institute. The author, Robyn Stone, offers a unique perspective.

“Over 1,000 people were impacted in my community!” exclaimed fifth-grade teacher Andrea Nelson upon realizing the power of her solutionary unit. “Solutionary” units are informed by the work of the Institute for Humane Education to help young people conduct research on global problems and find real-world, practical solutions. Nelson’s solutionary unit was custom designed to engage her 62 fifth-grade students. By leading students through a unit of investigation on waste, Ms. Nelson modeled how to be a solutions-oriented problem solver, a community leader, and an advocate for change.

Starting with the local phenomenon of waste in their classroom, Ms. Nelson’s students acquired key investigative tools such as data collection and analysis. These skills empowered students to lead bigger investigations that examined waste at the school site and, eventually, the impact of human waste on the world. Through this year-long investigation at Allen Elementary School in San Bruno, California, Ms. Nelson became a champion for environmental literacy at her site, inspiring other teachers and receiving recognition from the principal.

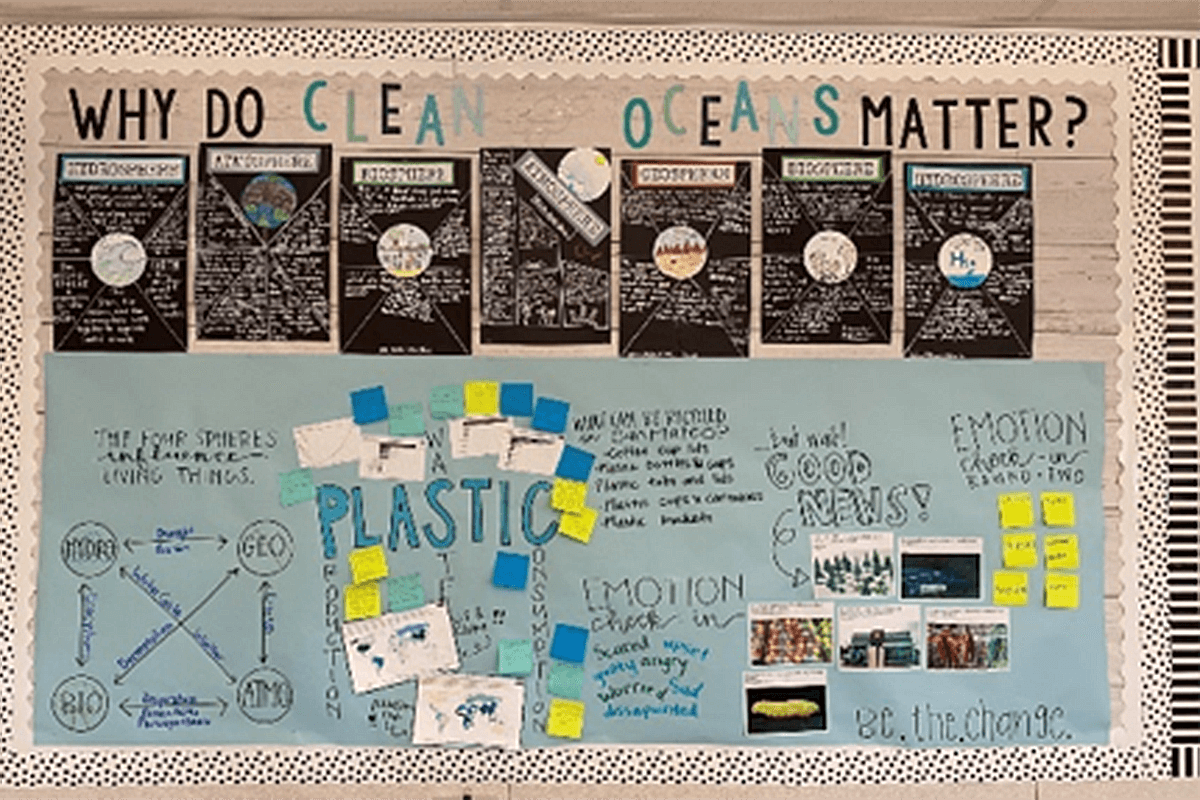

Andrea Nelson’s essential question to her students was, “How does human waste impact the world?” Ms. Nelson hoped that through web quests, self-surveys, and self-research, her students would recognize problems with trash disposal. Mini-lessons from the Institute for Humane Education and the California Education and the Environment Initiative supported problem investigation. Nelson carved out class time for students to work collaboratively sorting class and cafeteria rubbish bins in order to collect data on trash disposal.

Empowered by the knowledge constructed through their investigations, Ms. Nelson’s fifth graders led the trajectory of the investigation. As Ms. Nelson guided and facilitated their progress, students wanted to share their discoveries. They visited all first- through fourth-grade classes to share presentations about school-wide trash disposal problems and their student-driven solutions. They also formed a litter club, open to all K–5 students, which collects campus trash during lunch and recess, and they developed methods for teaching families about proper trash disposal, recycling, and composting. As a result, Ms. Nelson’s students are viewed by their younger peers as leaders in the community. Some students even wrote letters to the principal requesting action. “My students love to have a voice and see they can make a change,” concluded Ms. Nelson.

When I see how ten-year-old children can impact their communities, it inspires me to take the solutionary framework into other realms. For example, I appreciate how San Mateo County Office of Education (SMCOE) has added a Solutionary Expo to their annual Next Big Think event at the judged San Mateo County STEM Fair. As the coordinator of a large judged high school science fair in San Jose, I would like to offer Santa Clara County students the opportunity to showcase their efforts to engage in critical thinking, grapple with real local and global problems, and design solutions creatively. Imagine the power of high school students, many of whom are registered to vote, to go beyond the trifold science fair board and petition city hall for change!

As Andrea Nelson’s instructional coach for the San Mateo Environmental Learning Collaborative (SMELC), I supported her efforts in creating the unit, and I admired the way she supported her students in advocating for improved conditions at their school. It was an absolute pleasure to work with Ms. Nelson, and five other teachers in the cohort, during the 2019–2020 school year. My role as coach was to engage teachers in cycles of reflective practice about each stage of their solutionary unit’s evolution—design, implementation, and assessment. Watching the transformation of draft unit plans was awesome, from their early origins during the SMELC Science and Environment (SandE) summer institute in June 2019 to their final presentations at the SMELC capstone event January 27, 2020. Serving as a coach fulfilled my desire to increase the number of teachers who incorporate environmental literacy into K–5 integrated classroom curriculum.

Last year I became passionate about the necessity for educational leaders to see themselves as coaches who support teacher-leaders while I was completing work for my administrative services credential through Santa Clara County Office of Education’s LEAP. Before then, as STEM specialist and sustainability coordinator for the Harker School in San Jose, California, I had enjoyed a role in which I guided peers, supporting them with resources to help them weave environmental literacy into their classroom investigations. I was inspired by these efforts to support more teachers in the broader community, especially since there has been so much interest in environmental literacy since the passage of California’s Senate Bill 720, which incorporated environmental principles and concepts into the state’s Education Code.

When I attended the Schools for a Sustainable Future Summit in 2019, SMCOE environmental literacy coordinator Andra Yeghoian became my hero! I appreciated how she brought together education stakeholders from myriad places in the educational ecosystem, including school leaders, teachers, community education partners, and nonprofits. (Andra’s passion for community-based environmental learning and in-depth knowledge of NGSS, Common Core, and science pedagogy is so great that it has enabled SMELC to expand to the point where they can offer six summer institutes for 2020!)

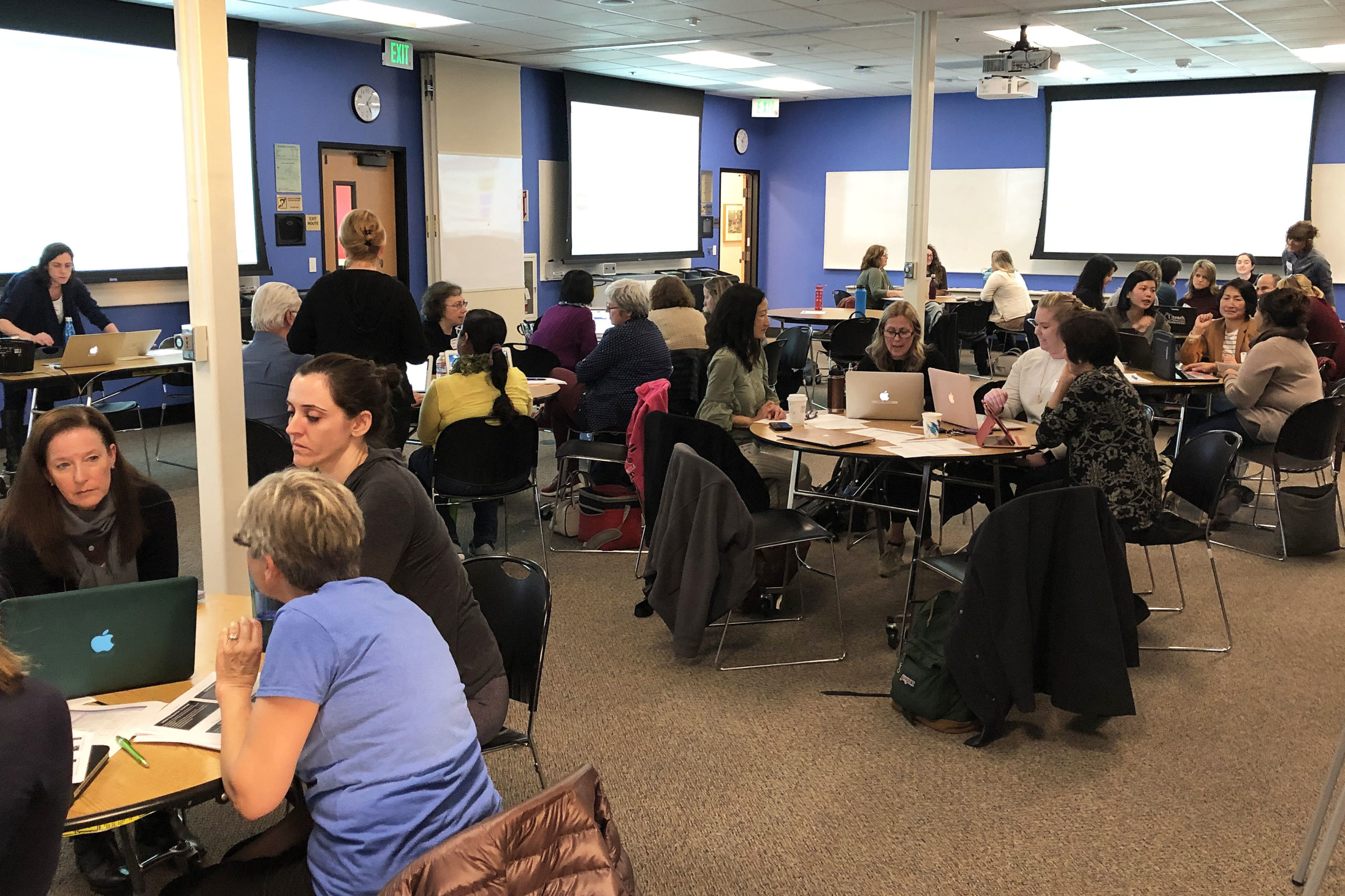

What I appreciate most about SMELC is how the programs are structured. Week-long intensive summer institutes bring together educators with wildly different perspectives from around the state. K–12 teaching fellows and coaches hail from public and private schools from Humboldt to San Diego counties. When the school year begins, the program matches fellows to coaches for ongoing support in the context of three cycles of reflection. Much like a supported bike ride, in which a team of folks has set up water stations and provides energy bars along the route, SMELC offers teachers customized guidance, from unit development to implementation to assessment.

I am grateful to Andra for giving me the opportunity to serve as a coach during the 2019–2020 SandE summer institute. Andra and her colleague Doron Markus, SMCOE science & engineering coordinator, led regular check-ins to support coaches in their efforts to support teachers. Andra and Doron modeled effective coaching leadership, which in turn helped me guide my mini-cohort. Throughout the institute, I served as sounding board, thought partner, NGSS standards genie, digital resource researcher, and matchmaker.

During the institute, teachers and coaches took deep dives into data literacy, simulations, systems thinking, modeling, notebooking techniques, and so much more. I was fortunate to support a group of fourth- and fifth-grade teachers. Working within the upper elementary grade bands, we were able to collaborate on big ideas and essential questions, lesson plans, resources, and teaching strategies. A key takeaway for me was how teachers can mitigate student emotional duress about climate change by building developmentally appropriate social and emotional learning into their units.

SMELC builds a system of leadership in environmental literacy, powered by coaching and mentoring. Students are empowered by supportive teachers who are empowered by supportive coaches who are empowered by supportive SMELC leaders. I admire the thoughtfulness and care that SMELC leaders, coaches, and teaching fellows exert while considering the myriad needs of the people they support. SMELC programs are commendable for their enduring impact on teachers, students, students’ families, and entire school communities.

SMELC fellows, like Andrea Nelson, are innovating how environmental science curriculum can be dynamically integrated with all content strands. Solutionary units of investigation are producing globally minded student citizens who see the interconnections between themselves and the world around them. Supporting SMELC teachers is truly inspirational work for me. I look forward to serving more teachers in the 2020–2021 cohort.